How Jean-Michel Basquiat and His Peers Made Graffiti Mainstream

A new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston explores how a network of young artists in 1980s New York City influenced hip-hop’s visual culture

![A large splash of yellow dominates the canvas, with handwritten phrases and drawings including three faces, the words HOLLYWOOD AFRICANS FROM THE [crossed-out] NINETEEN FORTIES, SUGAR CANE, TOBACCO, TAX FREE and other references](https://th-thumbnailer.cdn-si-edu.com/ckfYoMrWSRe1FZTwYoQ16Ny6wnA=/1000x750/filters:no_upscale()/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/e9/15e99383-e626-4ae8-a93a-21068571df27/untitled-1_1.jpg)

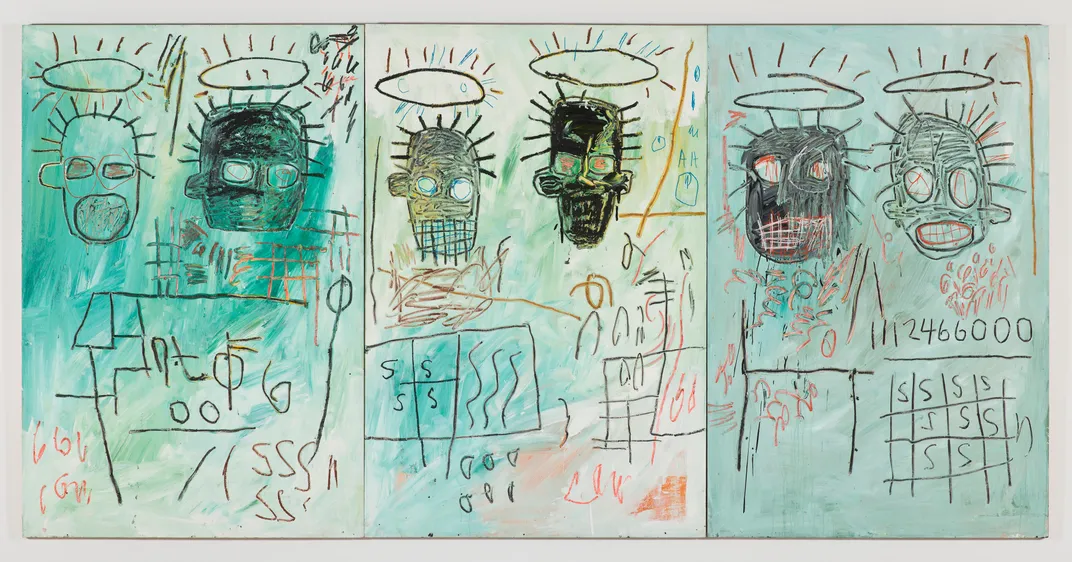

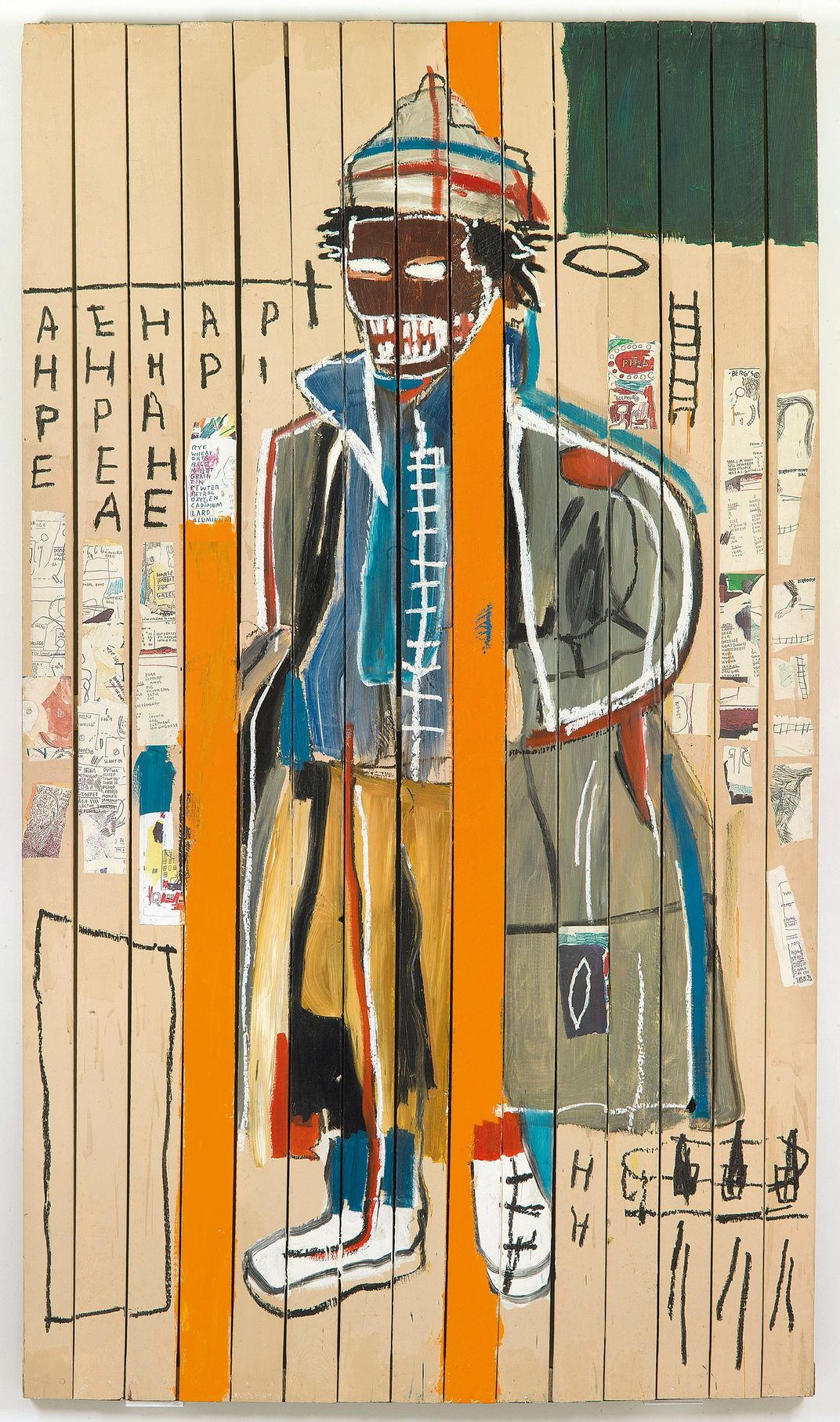

Contemporary accounts tend to mythologize the brief life of Jean-Michel Basquiat, who rocketed from New York City’s underground graffiti culture to worldwide acclaim before dying of a heroin overdose at just 27 years old.

Since his passing in 1988, critics and scholars alike have hailed Basquiat, whose large-scale works juxtaposed energetic colors and iconography to probe issues of colonialism, race, celebrity and systemic oppression, as a singular artistic genius; today, his paintings regularly fetch astronomical sums at auction.

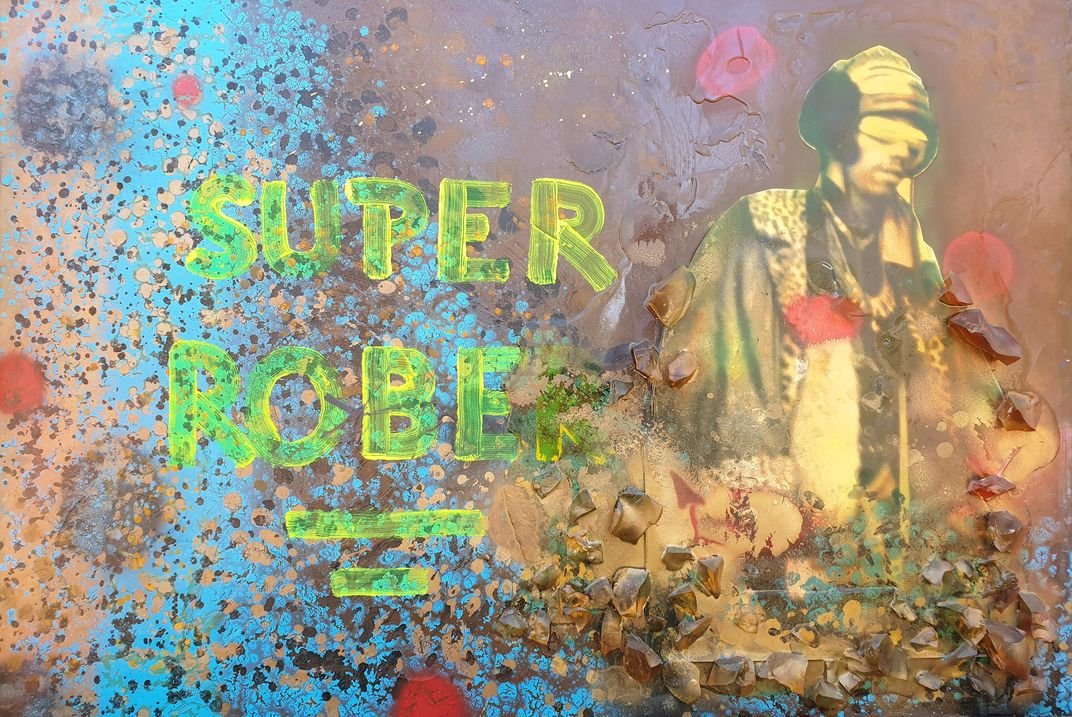

A new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston demystifies the image of Basquiat as a lone wolf, instead demonstrating how he honed his artistic sensibilities within a milieu of creative, boundary-breaking young peers on the forefront of hip-hop culture. These collaborators—among them legendary graffiti artist A-One, visual artist Fab 5 Freddy, artist and activist Keith Haring, graffiti and mural artist Lady Pink, and “Gothic futurist” Rammellzee—“fueled new directions in fine art, design, and music, driving the now-global popularity of hip-hop culture,” writes the MFA on its website.

As Gabriella Angeleti reports for the Art Newspaper, “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” is the first major show to consider the influence of Basquiat’s large network of mainly black and Latino collaborators, who worked alongside the artist in his early years but never achieved the same meteoric level of fame. Co-curated by MFA curator Liz Munsell and critic Greg Tate, the exhibition traces how a group of young artists involved in the hip-hop scene went from tagging subway cars to participating in the mainstream, white-dominated art world.

“Basquiat was an artist of his time and, after his early death, an artist for all time. ‘Writing the Future’ illuminates a less-explored aspect of his work and his mutually influential relationships with his peers,” says MFA director Matthew Teitelbaum in a statement.

He adds, “Basquiat and his friends knocked on the closed doors of the art world, the knock turned into a push and that push turned into a forceful toppling of long-established structures.”

Visitors can purchase timed-entry passes to the exhibition, which is on view through May 16, 2021, online. Interested participants can also listen to a playlist curated by Tate and watch select videos from the multimedia-heavy exhibition via the MFA’s website.

As Pamela Reynolds notes in a review for local NPR affiliate WBUR, the artists featured in “Writing” created art in a radically different New York City from the one known today. Amid an economic downturn, crumbling infrastructure and soaring unemployment, the city was “barely holding on,” she writes. This unlikely environment, in turn, sparked “a creative fermentation … that would brew a global revolution in art, music and design.”

Part of the exhibition space features a wide vestibule designed to resemble an art-adorned New York City subway station, reports Sebastian Smee for the Washington Post. Another gallery is “designed like a dance party.”

The overall experience, according to Reynolds, “takes us back to the moment when graffiti-splattered subway cars snaked around a decaying city, ushering in an electrifying shift in painting, drawing, video, music, poetry and fashion.”

The group that came to be known as “post-graffiti” artists—creatives who went from “bombing” subway cars to making commissions for buyers around the city—included Basquiat and several lesser-known friends: A-One, Lee Quiñones and other graffiti artists who began showing at the iconic Fun Gallery in the early 1980s. Among the artifacts on view is the Fun Fridge, a refrigerator that once stood in the East Village art space.

The show also contains a number of works by Rammellzee, a half-Italian, half-black artist from Queens who embraced the philosophy of “Gothic Futurism,” which “connected graffiti writers to a battle for free expression against authoritarian control,” as critic Murray Whyte explains for the Boston Globe.

Rammellzee’s depictions of futuristic warriors linked hip-hop to a nascent Afrofuturism—a visionary philosophy popularized most recently in the 2018 film Black Panther.

“By making the leap from trains to mass media and mainstream galleries, [these artists] were the ambitious shock troops of an incendiary cultural movement, the hip-hop revolution to come,” writes co-curator Tate in an exhibition catalog excerpt published by Hyperallergic. “In their subsequent careers (still ongoing in many cases) as internationally recognized visual artists, they have more than fulfilled the outsized dreams of their youth: to scale the art world’s defensive moats and battlements and reverse-colonize its exclusionary high castles.”

“Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) Boston through May 16, 2021.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)