How Did This Grasshopper End Up Trapped in a Vincent van Gogh Painting?

New research offers insights on “Olive Trees” (1889), including the story of the hapless insect trapped on its thickly painted surface

:focal(830x708:831x709)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/5f/265f9d47-e139-4994-aaf1-321b4e1f7c6f/grasshoper2.jpg)

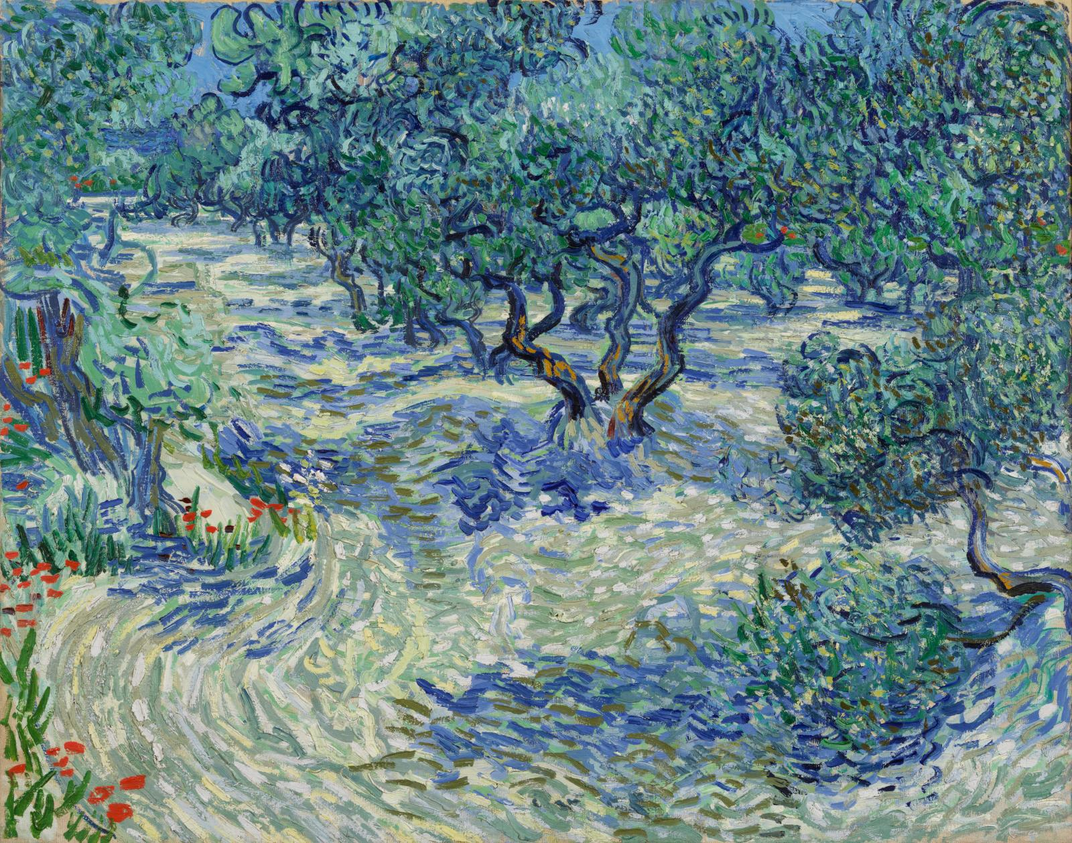

Four years ago, scholar Mary Schafer was examining Vincent van Gogh’s Olive Trees (1889), a swirling Impressionist landscape of green and blue olive groves, when she discovered a miniature surprise embedded in the thick impasto paint.

“I came across what I first thought was the impression of a tiny leaf,” Schafer, a conservator of paintings at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, told Live Science’s Rafi Letzer in 2017. “But then, I discovered it was in fact a tiny insect.”

As it turned out, Schafer had happened upon the preserved remains of an unfortunate grasshopper that had remained trapped in the lower right foreground of van Gogh’s painting for more than a century.

Now, reports van Gogh scholar Martin Bailey for the Art Newspaper, the museum has revealed additional information about the work on which the insect resides. Per a statement, researchers published a 28-page study of Olive Trees last month as part of a new online catalog dedicated to the Nelson-Atkins’ collection of French paintings.

The findings, available online in interactive or PDF form, note that the troubled artist created the painting during his stay at a mental health facility outside of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in southern France. When van Gogh moved there in May 1889 to treat his worsening mental health, his brother Theo instructed the institution’s director to afford him “the freedom to paint outside,” according to the Art Newspaper.

Over the next year—the final one of his life—van Gogh painted nearly 150 works, many of them completed outdoors. He began Olive Trees, which was likely inspired by the ancient olive groves in the nearby hills of Les Alpilles, in June 1889.

The Nelson-Atkins’ 1932 acquisition of Olive Trees marked only the second time that an American museum had purchased the Dutch Impressionist’s work. The first was an 1887 self-portrait bought by the Detroit Institute of Arts in 1922.

In the study, curators indicate that another piece of dried plant material similarly got caught in one of the artist’s brushstrokes. Van Gogh often painted outside, so it’s perhaps unsurprising that traces of the natural world landed on his canvases from time to time. As the Art Newspaper notes, the Rhône Valley’s strong wind—known as the mistral—probably posed an extra challenge for painting outside as the seasons changed. The blustery weather also increased the chances that debris might get caught in van Gogh’s thickly applied oil paints.

“Out of doors, exposed to the wind, the sun, people’s curiosity, one works as one can, one fills one’s canvas regardless,” the artist wrote in a September 1889 letter to Theo. “Yet then one catches the true and the essential.”

Conservators also discovered that van Gogh originally painted some of the shadows in Olive Trees a bright violet shade. The red pigments in the paint have faded over time, giving the work more of a blue hue today.

“The relationships between colors, and how they interact to intensify tones and create harmony, mood, and emotion, were essential to van Gogh,” explains Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, the Nelson-Atkins’ senior curator of European art, in the study. “[H]e was particularly interested in the juxtaposition of complementary colors.”

In Olive Trees, for instance, van Gogh places bright red streaks of poppies next to green leaves and “brilliant strokes of orange/yellow run alongside blue outlines of select trees,” according to Marcereau DeGalan.

As for the fate of the tiny bug, researchers indicate that the paint bears no signs of struggle, meaning the insect was likely already dead when it was blown onto the thick painted surface. The critter is small enough that audience members usually can’t identify it without direction (or a magnifying glass).

Seeing the small grasshopper embedded in van Gogh’s canvas can help viewers imagine the time and place in which it was painted, Marcereau DeGalan told NPR’s Colin Dwyer in 2017.

The curator added, “In an instant, it takes you to 1889 in a field outside the asylum where this bug had a bad day—or maybe a good day, because we’re thinking about it all these many years later.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)