How Did the ‘Great Dying’ Kill 96 Percent of Earth’s Ocean-Dwelling Creatures?

Researchers say the prehistoric mass extinction event could mirror contemporary—and future—devastation sparked by global warming

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/eb/68ebdd06-955d-4438-b1d7-72374bed640b/3982987607_0987aeb851_b.jpg)

Some 252 million years ago, an unparalleled mass extinction event transformed Earth into a desolate wasteland. Known colloquially as “The Great Dying,” the Permian-Triassic extinction wiped out nearly 90 percent of the planet’s species, including about 96 percent of ocean dwellers and 70 percent of terrestrial animals.

Scientists have long debated the exact causes of this die off, alternately blaming acid rain released by volcanic eruptions, mercury produced by basalt plateaus known as the Siberian Traps, and even incredibly high temperatures. But a new study published in the journal Science proposes a different culprit: global warming, a phenomenon the researchers say deprived the oceans of oxygen and left marine creatures to suffocate en masse.

And these findings are just the beginning of the bad news, Carl Zimmer reports for The New York Times. Over the past 50 years, global warming precipitated by carbon emissions has depleted the ocean’s oxygen levels by 2 percent. This figure will rise if humans fail to stem fossil fuel consumption, and if the Great Dying is any indication, the results could be disastrous.

As study co-author Curtis Deutsch, an oceanographer at the University of Washington, tells The Guardian’s Oliver Milman, “We are about a 10th of the way to the Permian. … That’s a significant fraction and life in the ocean is in big trouble, to put it bluntly.”

Expanding on this warning in an interview with The Atlantic’s Peter Brannen, Deutsch says that the planet is projected to warm around 3 to 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. In an absolute worst-case scenario where all of Earth’s fossil fuels are burned, this number could jump to 10 degrees Celsius—the same level of warming that triggered the Great Dying.

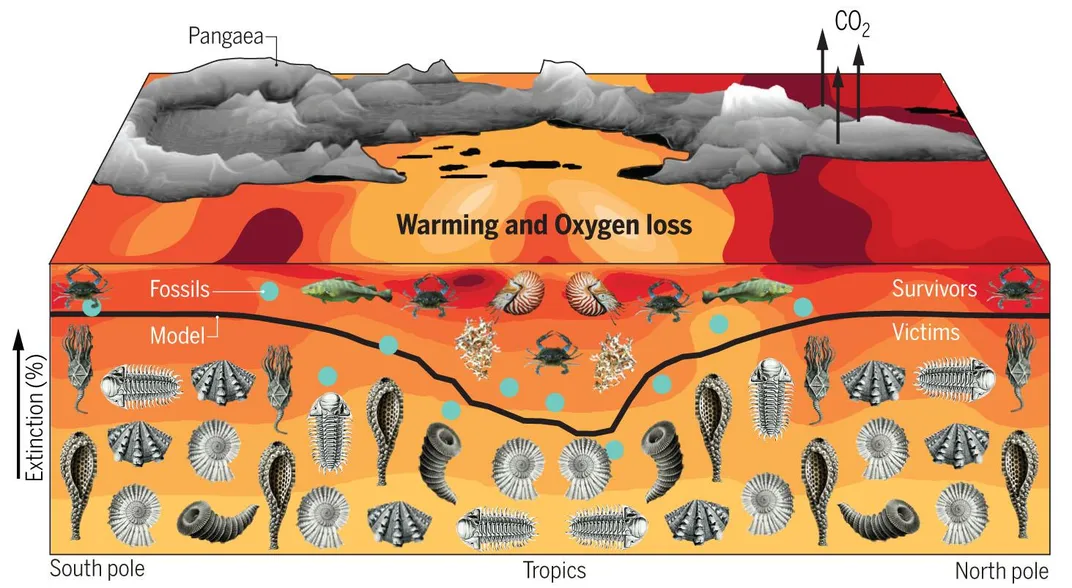

To better understand the prehistoric mass extinction event, Deutsch and co-author Justin Penn, also of the University of Washington, created a large-scale computer simulation that modeled Earth’s transition from the Permian Period to the Triassic. At the time, most of the planet’s land mass was clumped together in the supercontinent of Pangea, but as Evan Bush notes for The Seattle Times, the climate was surprisingly similar to contemporary conditions.

Then, a series of volcanic eruptions in the Siberian Traps—Seth Burgess, a geologist and volcanologist with the United States Geological Survey who was not involved in the study, tells Bush the explosions produced enough lava “to cover the area of the United States … [up to] a kilometer deep”—released greenhouse gases that sparked a roughly 10-degree Celsius rise in surface temperatures.

As Earth’s land heated up, so did its oceans. According to Live Science’s Megan Gannon, the researchers found that ocean temperatures rose by around 11 degrees Celsius, making global marine oxygen levels drop by 76 percent. Creatures living in seafloor environments were hit the hardest, with roughly 40 percent of these deep-sea dwellings lacking oxygen entirely.

Given the similarities between the climate during the pre-extinction event and contemporary climate, the researchers used data on temperature and oxygen sensitivities garnered from 61 modern animals, under the assumption it would generate comparable results. They found that most marine creatures would’ve had to find new habitats in order to survive. Those living in the tropics had the best chances of survival, as they were already accustomed to warmer temperatures and lower oxygen levels, while those living at higher latitudes where oxygen-rich cold water was paramount were largely doomed.

The late-Permian fossil record supports the researchers’ projections, indicating that the combination of climate warming and oxygen loss sparked by the Siberian eruptions had an outsized effect on animals living near the poles. The tropics still experienced what The Atlantic’s Brannen describes as “an unthinkable cataclysm,” but they emerged with marginally better odds.

The implications of these findings paint a dire portrait of Earth’s future. As Penn tells UW News’ Hannah Hickey, “Under a business-as-usual emissions scenario, by 2100 warming in the upper ocean will have approached 20 percent of warming in the late Permian, and by the year 2300 it will reach between 35 and 50 percent.”

In other words, time is running out, and if drastic action isn’t taken, the ongoing sixth great extinction could become the second Great Dying.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)