A Tale of Two White Houses

The Confederacy had its own White House—two, actually

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/11/44/11445432-cf1f-4b3f-85c5-61515c8b35e5/wh.jpg)

For most of the Civil War, the Confederacy had its own White House.

In a physical illustration of how intimate a conflict the Civil War was, the two White Houses weren’t all that far apart—just 90 miles separated the Executive Mansion of the Confederacy, in Richmond, and the White House in Washington DC.

“One overlooked the Potomac River and the other the James,” writes The White House Historical Association. The similarities didn’t stop there: the two buildings originally had very similar architecture, although they diverged as later additions were attached.

Their occupants—Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis—also bore similar burdens, writes the association. After inauguration:

Both men went to their capitals on the train, and both took their families. Before each was a future that can only have seemed puzzling and, at its worst moments, rightly imagined as an impending nightmare. To his friends in Springfield, Lincoln spoke from the back of the departing train: “No one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. . . . I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I will return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of that Divine Being, who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail. . . . Let us confidently hope that all will yet be well.”

Two days after his inauguration in Montgomery, Davis wrote to his wife: “I was inaugurated on Saturday night. The audience was large and brilliant upon my heavy breast was showered smiles plaudits and flowers, but beyond them I saw troubles and storms insurmountable. We are without machinery without means and threatened by powerful opposition but I do not despond and will not shrink from the task imposed upon me.”

After his February 1861 inauguration, Davis and his family originally stayed in an Montgomery, Alabama home referred to as the First White House of the Confederacy:

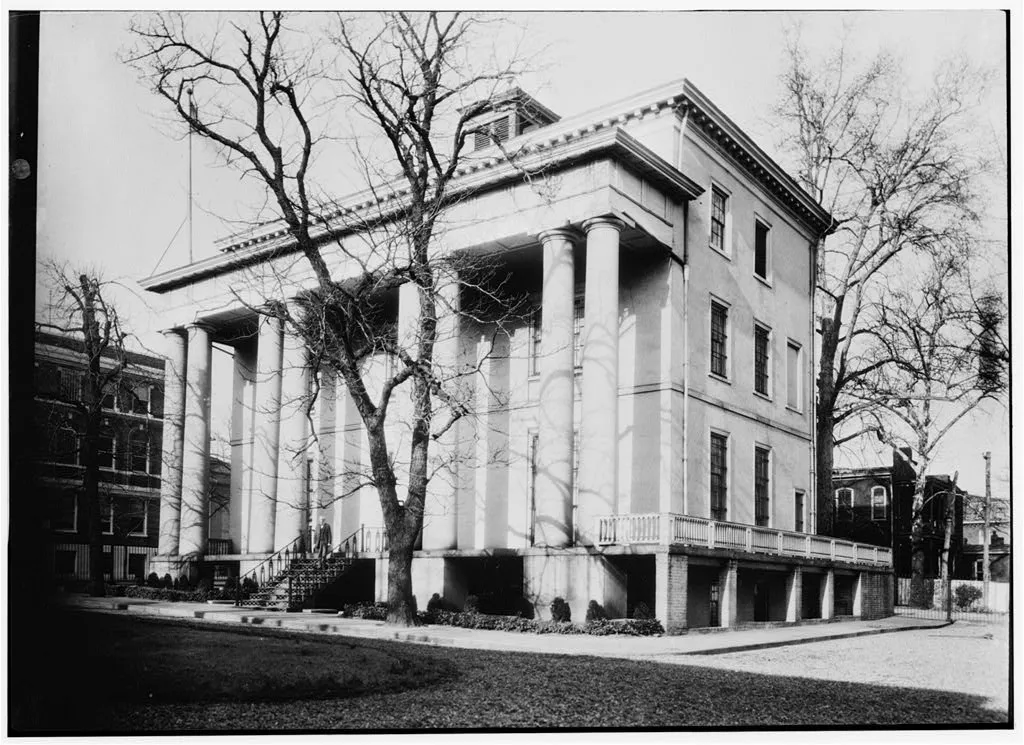

Then when the capital of the Confederacy moved to Virginia in August 1861, the Davis family moved to Richmond, Virginia, into the building most commonly referred to as the White House of the Confederacy:

It was from the second White House of the Confederacy that Davis's family fled Richmond on April 3, 1895, six days before General Robert E. Lee's army surrendered.

Both leaders—Davis and Lincoln—had endured personal tragedies at their respective White Houses: Davis's son Joseph died in a fall from a porch, according to the National Park Service. Abraham Lincoln's third son, Willie, died at the White House, likely of typhoid fever.

After the Confederate government evacuated Richmond, they headed for Danville, Virginia, and began trying to govern in exile. In time, Davis was captured, writes Rebecca McTear for Today I Found Out, and attempts were made to prosecute him before he was pardoned as part of Andrew Johnson’s blanket pardon “to all persons who participated in the ‘rebellion.’

Both Confederate White Houses survived Reconstruction, and are now museums. The interior of the White House of the Confederacy has been recreated to look something like it would have during Davis’s time there.