How “Learned Deafness” Might be Letting Noise Pollution Win

The world may be noisier than ever but one scientist warns that our attempts to blot out the sound may cost us dearly

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/0b/450bc5c6-fe44-469e-b640-b8d882f20db8/noise_pollution_42-67422520.jpg)

There’s nothing quite like the gentle sounds of birds chirping, bugs buzzing or rain drops pattering over a canopy of leaves. But these days, such seemingly mundane noise can be hard to come by. There are car horns and airplane engines, the whir of machinery and the electric hum of power lines.

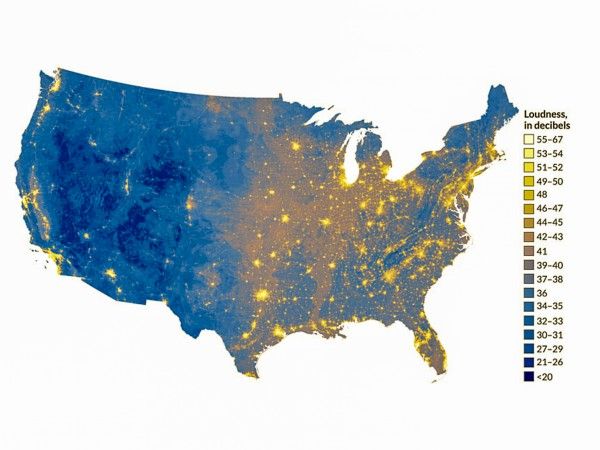

A new map compiled by researchers at the National Parks Service has shown just how difficult it’s gotten to secure a slice of silence. Depicting high background noise levels in yellow and low levels in blue, the map consists of data collected over 1.5 million hours of acoustic monitoring from all over the country:

Unsurprisingly, urban areas are the noisiest, while those questing for quiet can find it on pre-European colonization levels in large swaths of the west.

But one scientist is now warning that all that sound and our efforts to avoid it might actually be allowing noise pollution to get worse—and could cause a phenomenon he’s calling “learned deafness." To control the sounds in our own personal worlds, we might resort, for instance, to wearing headphones that blare our favorite music in our ears. (It can make the day nicer, not having to listen to that bus chug by or the cabbie screaming out his window.) Or we might just close our ears off and ignore the auditory stimuli of the world around us.

Kurt Fristrup, a senior scientist at the U.S. National Park Service, spoke this week to a group of scientists about the country’s rising level of background noise and the resulting tune-out of natural sounds, the Guardian reports. “This learned deafness is a real issue. We are conditioning ourselves to ignore the information coming into our ears,” he said.

“There is a real danger, both of loss of auditory acuity, where we are exposed to noise for so long that we stop listening, but also a loss of listening habits, where we lose the ability to engage with the environment the way we were built to,” he added.

Fristrup compared the problem to the effect fog would have on how you perceive a landscape. You see only a small portion of what’s in front of you. “Even in most of our cities there are birds and things to appreciate in the environment, and there can be very rich natural choruses to pay attention to. And that is being lost,” he warned.

Should we keep blotting out the noise pollution with music and noise-cancelling headphones on an individual level, we risk allowing the wider background noise to further crescendo. This could have a larger effect on the animals and insects that use sound to hunt and communicate—let alone drive all of us a little closer to crazy.

And here’s a good reason to turn down the music: Preliminary research presented at the same meeting shows that recordings of sounds from national parks likely have the power to help us more quickly recover from stressful events. No one's sure exactly why this works, but, as the Guardian reports, researchers think there might be an evolutionary element at play. To our ancestors, the peaceful chatter of animals and bugs may have been an auditory indication of safety in the absence of predators.

So, next time you reach for the iPod on your walk to work, consider straining for nature’s noise instead—it might just give you a little stress relief and could help maintain your ears’ ability to hear all that the wide world has to offer.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)