How the NSA Stopped Trying to Prevent the Spread of Encryption And Decided to Just Break It Instead

The NSA spent decades trying to stop the spread of encryption technology

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2013090611202209_06_2013_bombe.jpg)

Yesterday, the ongoing, Edward Snowden–fueled investigation into the National Security Agency broke yet more new ground with the revelation that the agency can break the lock off the vast majority of the information streaming around the internet. The New York Times:

The agency has circumvented or cracked much of the encryption, or digital scrambling, that guards global commerce and banking systems, protects sensitive data like trade secrets and medical records, and automatically secures the e-mails, Web searches, Internet chats and phone calls of Americans and others around the world, the documents show…The encryption documents now show, in striking detail, how the agency works to ensure that it is actually able to read the information it collects.

But this revelation is just the latest in the decades-long battle between the NSA and corporate America. The agency began as a military code breaking agency in World War II and worked through Korea, Vietnam and the Cuban Missile Crisis. While focused largely on cracking military codes, the agency was also a powerful force behind the development of new encryption technologies, says the NSA’s National Cryptological Museum. And as encryption has become more widespread in the past few decades, the NSA has tried to control how much other organizations could keep secret.

The 1970s and the Dawn of Widespread Encryption

In the 1970s, ARPANET was sweeping the nation, a precursor to the internet that connected academics and military scientists. Alongside the growth of this sprawling network, says Matt Novak for Paleofuture, “civilian researchers at places like IBM, Stanford and MIT were developing encryption to ensure that digital data sent between businesses, academics and private citizens couldn’t be intercepted and understood by a third party.” Intelligence services, including the NSA, really didn’t like this.

When the NSA couldn’t get the researchers to stop their work, they flipped tactics, instead offering to help them out. That didn’t exactly reassure the scientists. “Naturally, in the Watergate era, many researchers assumed that if the U.S. government was helping to develop the locks that they would surely give themselves the keys, effectively negating the purpose of the encryption,” says Novak. They declined the offer of help.

The “Crypto Wars”

In the 1970s, access to data networks like ARPANET remained fairly limited, but in the 1990s, that all started to change. The internet was growing, and cell phones were coming online. The NSA, again, really didn’t like that there were technologies out there that they didn’t have the keys to.

Having failed in the 1970s to stop the spread of encryption technology, the NSA was intent on redoubling its efforts. But the agency ran into the blossoming tech sector. In what came to be remembered as the “crypto wars,” says Wired, the NSA ran up against Silicon Valley.

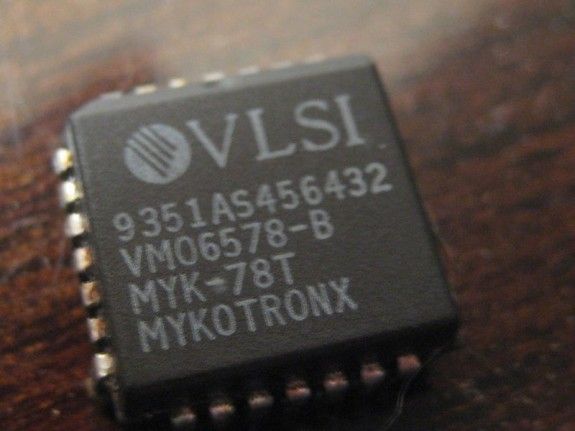

The NSA tried to get a small device, known as the Clipper Chip, installed in electronics. The chip would give them backdoor access to communications. TechCrunch:

“A subculture clash became a battle between Microsoft at the height of its powers and a national security establishment,” recalls Baker, who argues that the need to export products, especially for e-commerce, compelled the business community to win over members of Congress.

Eventually, business beat surveillance, and the widespread encryption—free from NSA back doors—became the norm. TechCrunch:

Lobbying alone didn’t topple the Clipper Chip and export controls. Three months before the White House caved into the tech industry, the Ninth Circuit of appeals struck down export controls on First Amendment grounds.

“Government efforts to control encryption thus may well implicate not only the First Amendment rights of cryptographers intent on pushing the boundaries of their science, but also the constitutional rights of each of us as potential recipients of encryption bounty,” explained the landmark Bernstein vs. US Department of Justice decision.

Now

With the NSA’s desire to keep encryption technology to itself long thwarted and widespread backdoor access nixed, the agency changed tactics. Which brings us back to today. The New York Times:

“For the past decade, N.S.A. has led an aggressive, multipronged effort to break widely used Internet encryption technologies,” said a 2010 memo describing a briefing about N.S.A. accomplishments for employees of its British counterpart, Government Communications Headquarters, or GCHQ. “Cryptanalytic capabilities are now coming online. Vast amounts of encrypted Internet data which have up till now been discarded are now exploitable.”

More from Smithsonian.com:

See How Fast ARPANET Spread in Just Eight Years

400 Words to Get Up to Speed on Edward Snowden, the NSA And Government Surveillance

Today’s the Day the NSA’s Permission to Collect Verizon Metadata Runs Out

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)