How to See a Stunning Supermoon and Partial Lunar Eclipse on Tuesday

September’s full moon delivers a rare trifecta for lunar enthusiasts: a supermoon, a partial eclipse and a harvest moon

:focal(2250x1404:2251x1405)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3e/73/3e736ef9-b1c9-43dd-a67e-a44e8a766611/gettyimages-1753034547.jpg)

September is a big month for lunar enthusiasts. This month, skygazers can enjoy a rare combination of a harvest moon, a supermoon and a partial lunar eclipse—at the same time.

The moon will appear to be full for roughly three days next week, starting Monday evening and extending through Thursday morning. But the full moon will officially occur on Tuesday night at 10:35 p.m. Eastern Time, writes Gordon Johnston for NASA.

Following the “super blue moon” that occurred in August, Tuesday’s event is the next in a series of lunar spectacles for the rest of the year. Here’s what you need to know.

A “bite” out of the moon

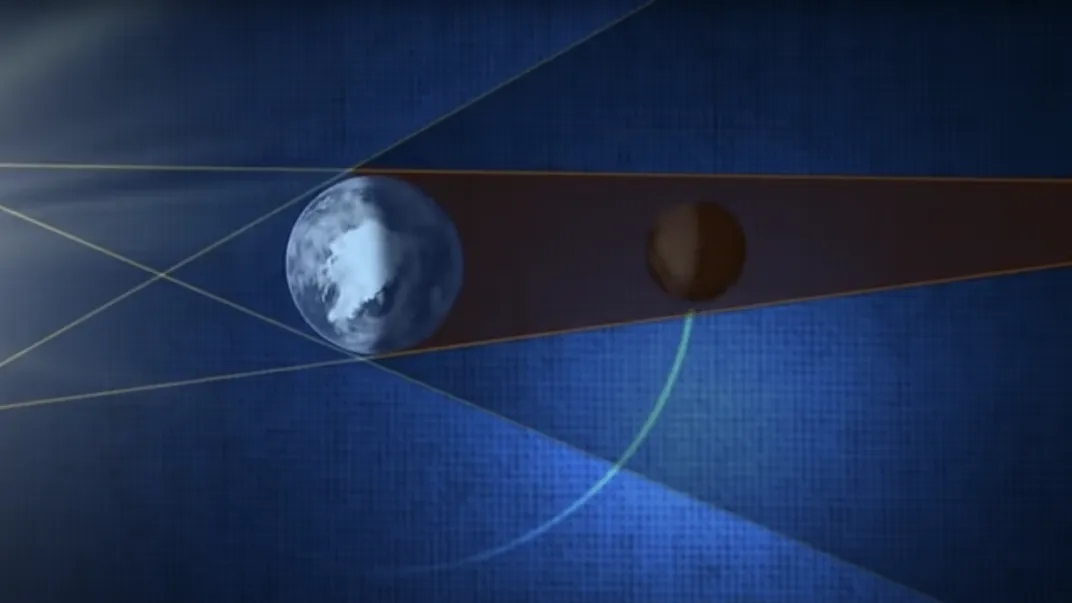

Lunar eclipses occur during some full moons, when our natural satellite passes through Earth’s shadow. During a total lunar eclipse, the surface of the full moon takes on a red hue, as Earth’s atmosphere scatters away the blue wavelengths of sunlight, leaving only the red light to illuminate the moon. A partial lunar eclipse, however, looks different.

“You’ll see a little bite taken out of one side of the moon over about an hour,” writes NASA’s Preston Dyches.

If you’re hoping to catch a glimpse of the partial lunar eclipse, you’ll want to head outside in the evening. The moon will begin entering Earth’s outer shadow, known as the penumbra, at 8:41 p.m. Eastern Time, according to NASA. The eclipse will reach its peak at 10:44 p.m., when the top 8 percent of the moon will be in Earth’s darker inner shadow, the umbra. (You can see the full timing breakdown based on your location on Time and Date.)

As far as eclipses go, this one is “minor,” writes Bob King for Sky & Telescope. But, since it doesn’t require staying up too late and will be visible throughout North America, the September lunar eclipse presents a good opportunity to watch a rare celestial spectacle that typically only happens a few times per year—and in some years, not at all.

You’ll have the best view if you look at the moon through a telescope or a pair of binoculars, but you should also be able to see the eclipse with the naked eye.

“With or without a telescope, the smooth curve of the dark umbra on the lunar disk will be a nice reminder to us, as it was a divine revelation to the ancient Greeks, that our Earth is round,” writes Joe Rao for Space.com.

You might also consider this month’s partial lunar eclipse a warm-up for the annular “ring of fire” solar eclipse taking place on October 2, which will be visible from the southern tip of South America.

A super harvest moon

September’s full moon is also a supermoon, which means it will appear bigger and brighter than usual. That’s because the moon will be closer than normal as it orbits around the Earth. September’s full moon is the second of four consecutive supermoons this year. The next one, in October, will be even closer to Earth, but only marginally—according to NASA, the full moons of September and October are “virtually tied” for the closest of the year.

Though you might not be able to notice the slight difference in size—most casual observers don’t pick up on the size difference between a supermoon and a regular full moon—Tuesday’s full moon will appear to be about 7 percent larger than the average.

Finally, since it’s the closest full moon to the autumnal equinox on September 22, the September full moon is also known as a harvest moon. The term, which dates back to at least 1706, is closely linked with agriculture.

“Unlike other full moons, this full moon rises at nearly the same time—around sunset—for several evenings in a row, giving farmers several extra evenings of moonlight and allowing them to finish their harvests before the frosts of fall arrive,” writes Catherine Boeckmann for the Old Farmer’s Almanac.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SarahKuta.png)