How Zika Virus Could Be Used to Fight Brain Cancer

The same properties that make Zika virus devastating to fetal brains could be turned against cancer cells

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/e2/9be2ecb6-552b-442f-baad-b9a2a0a666d7/149072.jpg)

In 2015, the specter of Zika loomed worldwide. The virus quickly became known for causing a spate of babies from infected mothers to be born with microcephaly—a condition marked by malformation of the brain. Now, scientists are harnessing the same properties that make the virus so deadly in fetuses and turning them toward a positive goal: fighting brain cancer.

Zika is a mosquito-borne disease that is mainly spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. In adults, symptoms are usually mild, but for developing fetuses, the impacts can be devastating. The virus is capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier and seems to preferentially attack the stem cells that grow into a developing baby's brain. But by hijacking this deadly property, researchers are using Zika to target the cancerous cells of glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer found most commonly in adults, reports Michelle Roberts for BBC News.

More than 12,000 people in 2017 have been or are expected to be diagnosed with glioblastoma, according to the American Brain Tumor Association. Those people join the ranks of a long list of notable people diagnosed with the cancer, including Sens. John McCain and Ted Kennedy, composer George Gershwin and death rights activist Brittany Maynard. Treatments are rarely effective long term, and most people diagnosed with the cancer die within a year.

But the researchers thought that Zika's preference for these "precursor cells" could be used against the growing tumor cells, explains Michael Diamond, an infectious disease researcher at Washington University of St. Louis, in statement. Adult brains usually have few such stem cells in their brains but tumors are formed by the overgrowth of stem cells and precursor cells, writes Nathaniel Scharping for Discover.

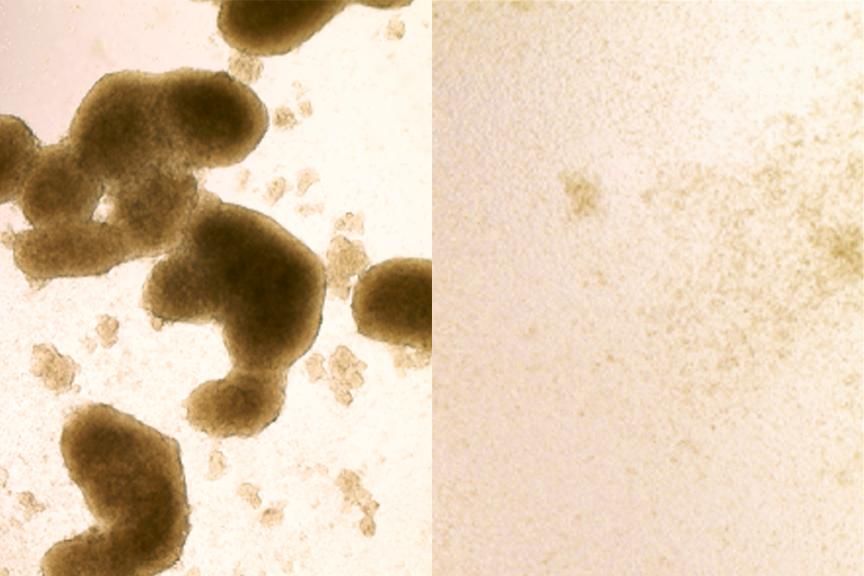

To test this idea, Diamond and other researchers infected glioblastoma tumors grown in a dish with Zika virus to see how the virus affected the cancer cells. They also gave Zika virus infections to mice implanted with glioblastoma tumors, reports Clare Wilson for New Scientist.

The results, published this week in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, were promising. Just like it seeks the neural precursor cells in fetuses, the Zika virus targeted the stem cells of the Petri dish-grown glioblastoma, infecting and killing the cells while largely sparing non-cancerous cells, reports Wilson. And a significant number of the cancer-stricken mice infected with a mouse-adapted version of the disease lived longer than the controls.

There is still much more work to be done to confirm the results. Since intentionally infecting people with Zika virus is a dangerous method of treatment, researchers are working to develop a weaker version of the virus for tests of the cancer treatment in humans, reports Roberts.

"We're going to introduce additional mutations to sensitize the virus even more to the innate immune response and prevent the infection from spreading," Diamond says in a second statement. "Once we add a few more changes, I think it's going to be impossible for the virus to overcome them and cause disease."

Diamond hopes to begin human trials of that version in about 18 months. He envisions future treatments to be paired with existing chemotherapy methods. But other researchers aren't planning to wait. As Wilson reports, Cambridge University neuroscientist Harry Bulstrode is considering trials using natural Zika virus on humans with glioblastoma. If successful, the viral treatment would join a long history of treating cancer with viruses, such as the use of modified herpes to fight melanoma.