Huge 19th Century Circus Poster Found in Walls of Wisconsin Bar

It advertised an 1885 performance by the Great Anglo-American Circus

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d6/cf/d6cfbd8f-b088-440e-94e2-ec9c01fbf365/img_1833.jpg)

Since the 1970s, the family-owned Corral Bar has been serving drinks and hearty meals to diners in the small town of Durand, Wisconsin. But the property has a much longer history: it sits on land that was first surveyed in 1857 and has been home to a succession of stores, barber shops and saloons. As Eric Lindquist reports for the Eau Claire Leader-Telegram that one of the bar’s current owners, Ron Berger, recently revealed a vibrant relic of the Corral’s rich past: a nine-foot-high, 55-foot-long circus poster, long hidden behind the bar’s walls.

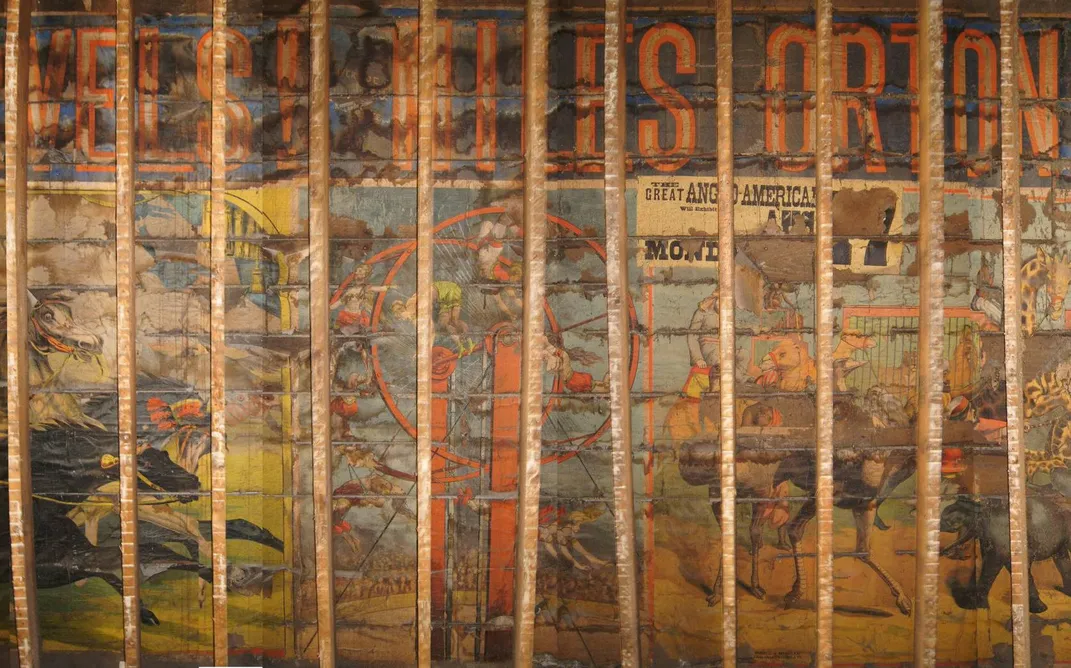

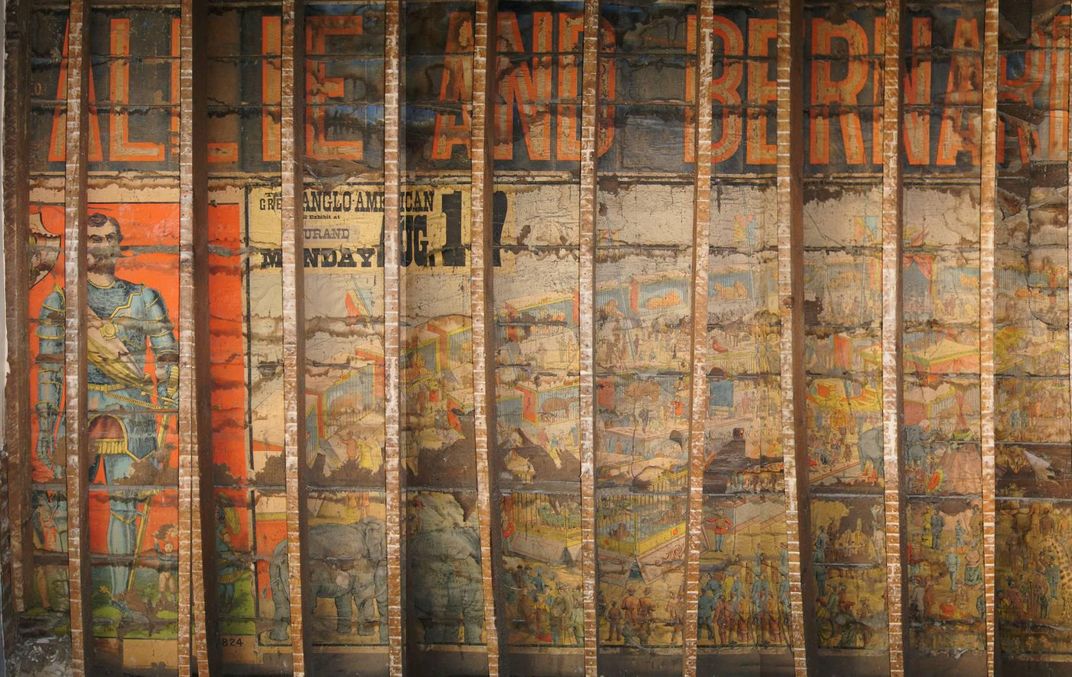

This remarkable discovery came to light in 2015, when Berger embarked on a project to expand the Corral Bar and Riverside Grill—as the joint has been known since 1996, when a full-service kitchen and dining area were added—into an adjacent property. He cut a hole into one of the Corral’s walls and was surprised to see an illustration of a bison staring back at him. Over the following weeks, he gradually uncovered an entire circus scene: lions, giraffes, sea creatures, elephant riders and aerialists, all meant to entice locals to the Great Anglo-American Circus.

A large stamp indicated that the world-renowned circus would be performing in Durand on August 17 and, after consulting archival records, Berger was able to determine that the year of the show was 1885. Block lettering across the top of the poster advertised a star performance by the circus’ owner, Miles Orton, who was known for standing atop a galloping horse while holding two child acrobats, Allie and Bernard, on his shoulders. “ALLIE & BERNARD, TINY AERIAL MARVELS, MILES ORTON RIDES WITH US!” the poster proclaimed.

The artwork originally would have been visible from the Chippewa River, so it could broadcast the circus to passing boat traffic. Berger tells Atlas Obscura’s Evan Nicole Brown that he thinks the circus performers were given permission to slap their poster on the wall of a building that was in mid-construction. Later, builders covered up with wall without bothering to take the poster down, but the details of the relic’s history are not certain.

It is certain, however, that the artwork’s survival to the present day is a small wonder. The poster is a lithograph—a print made by stamping carved woodblocks onto paper. And like other circus posters, it was meant to fall apart after a few months. “They were designed to not have to have a team come back to take them down,” Berger tells Brown.

The poster is also a prime example of the ways in which circuses were at the forefront of the early ad industry. The famed showman P.T. Barnum has, in fact, been called the “Shakespeare of Advertising.” In the years before radio and television, circus workers plastered towns with colorful posters promising remarkable acts and exotic animals. Sensationalism was important, veracity less so; the Corral Bar poster, for instance, appears to feature a number of sea monsters and prehistoric fish.

“Circuses, in their day, were pioneers of mass media and in-your-face, bombastic advertising,” Pete Schrake, archivist at Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin, tells Lindquist.

The poster in the Corral Bar survived to the present day in relatively good shape, but it still took Berger and a team of experts two years to restore it. After removing the outer wall, they had to micro-vacuum the artwork, re-stick the peeling pieces and then carefully wash the 134-year-old advertisement. Today, the poster is encased in protective glass, but clearly visible to the bar’s visitors—a reminder of that exciting day in 1885 when the circus came to town.