Enormous Roman Shipwreck Found Off Greek Island

The 110-foot-long ship carried more than 6,000 amphorae used as shipping containers in the ancient world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bb/75/bb75fdcc-ec36-41bc-b921-6b902e4415af/_3587752_orig.jpg)

Researchers exploring the waters off the Greek Island of Kefallinia have unearthed one of the largest Roman-era shipwrecks ever found.

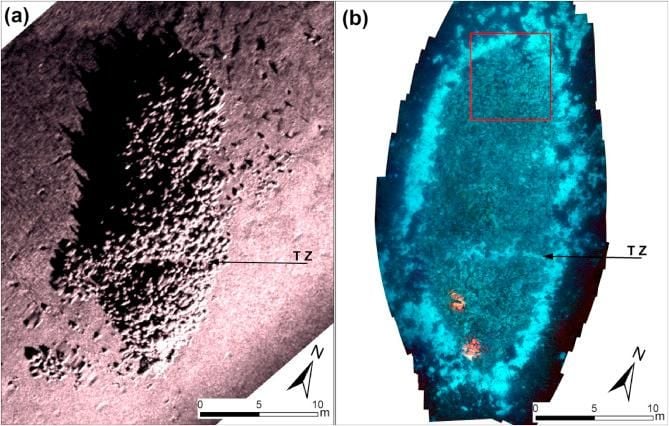

As Julia Buckley reports for CNN, a team from Greece’s University of Patras located the remains of the ship, as well as its cargo of 6,000 amphorae—ceramic jugs used for shipping—while conducting a sonar scan of the area. The 110-foot-long vessel, newly detailed in the Journal of Archaeological Science, was situated at a depth of 197 feet.

According to the paper, the “Fiscardo” wreck (named after a nearby fishing port) was one of several identified during cultural heritage surveys undertaken in the region between 2013 and 2014. Researchers also discovered three nearly intact World War II wrecks: specifically, two ships and a plane.

The vessel is among the four largest Roman shipwrecks found in the Mediterranean Sea to date; experts think the ship is the largest ever unearthed in the eastern Mediterranean.

Based on the type of amphorae found in the Fiscardo ship’s cargo, the team dates the wreck to sometime between the first century B.C. and the first century A.D.—roughly around the time of the rise of the Roman Empire. Four other major Roman wrecks are scattered across the surrounding sea.

“[The shipwreck] provides further evidence that the eastern Ionian Sea was part of an important trading route ferrying goods from the Aegean and the Levant to the peri-Adriatic Roman provinces and that Fiscardo port was a significant calling place,” write the study’s authors in the paper.

The researchers hope to conduct more extensive archaeological examination of the ship, which likely boasts a well-preserved wooden frame. They hope the wreck will reveal new information on Roman shipping routes, including what types of goods were traded, how cargo was stowed aboard and how the vessel was constructed.

Lead author George Ferentinos tells New Scientist’s Ruby Prosser Scully that he thinks the extra effort would be worthwhile.

He adds, “It’s half buried in the sediment, so we have high expectations that if we go to an excavation in the future we will find part or the whole wooden hull.”

Still, says Ferentinos, performing a full-scale study of the ship would be a “very difficult and costly job.” For now, the team is sticking to more modest goals, like recovering “an amphora and using DNA techniques to find whether it was filled with wine, olive oil, nuts, wheat or barley.”

Eventually, the team may seek an investor to turn the site into a diving park.

The Fiscardo ship isn’t the only wreck reshaping archaeologists’ understanding of Roman trade routes. Over the summer, researchers in Cyprus discovered the first “undisturbed” Roman shipwreck ever found in that nation. Located off the coast of Protaras, the ship probably carried oil or wine and came from the Roman provinces of Syria and Cilicia.

And last month, Greek archaeologists identified five new shipwrecks off the island of Kasos, including one dated to the end of the fourth century B.C. and another from the first century B.C. A third ship was dated to the later Byzantine period, while the remaining two were linked with the Greek War of Independence, which took place during the 1820s.