A Human-Sized Penguin Once Waddled Through New Zealand

The leg bones of Crossvallia waiparensis suggest it was more than five feet tall and weighed up to 176 pounds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/ce/2bce01d3-1556-44a0-8bac-d4c114df702d/screen_shot_2019-08-14_at_31254_pm.png)

Last week, the world was introduced to “Squawkzilla,” a hulking ancient parrot that made its home in New Zealand some 19 million years ago. Now, the country’s roster of extinct bulky birds—which includes the massive moa and the huge Haast’s eagle—has grown even larger, with the discovery of a Paleocene-era penguin that stood as tall as a human.

The ancient avian came to light thanks to an amateur palaeontologist named Leigh Love, who found the bird’s leg bones last year at the Waipara Greensand fossil site in North Canterbury. The Waipara Greensand is a hotbed for penguin remains dating back to the Paleocene, which spanned from 65.5 to 55.8 million years ago; four other Paleocene penguin species have been discovered there. But the newly unearthed fossils represent “one of the largest penguin species ever found,” Paul Scofield, co-author of a new report in Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology and senior curator at the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, tells the BBC.

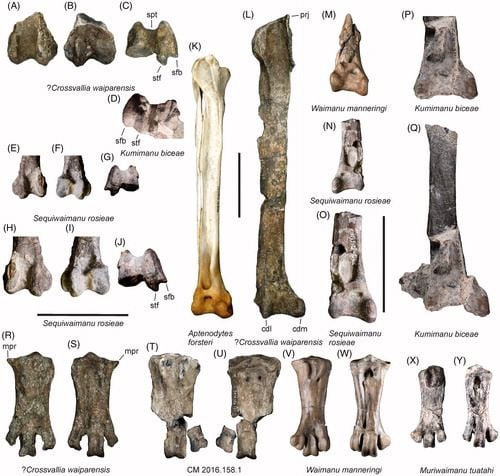

Dubbed Crossvallia waiparensis, the penguin soared to a height of around five feet and two inches, and weighed between 154 and 176 pounds. That makes the bird considerably bigger than the largest extant penguin species, the Emperor penguin, which can grow to around four feet tall and weigh up to 88 pounds. Based on the analysis of C. waiparensis’ leg bones, Scofield and his colleagues think the species’ feet played a bigger role in swimming than those of modern penguins, but it is also possible that the bird had not fully adapted to standing upright.

C. waiparensis likely grew to its impressive size due to the same factor that fuelled New Zealand’s other towering bird species: a lack of predators. The penguin evolved in the wake of the Cretaceous period, which culminated in the extinction of not only dinosaurs, but also large marine reptiles that once stalked the Earth’s seas. With no major marine competitors, C. waiparensis burgeoned in size, thriving for around 30 million years—until large sea-dwelling mammals like toothed whales and pinnipeds arrived on the scene.

“[T]he extinction of very large-sized penguins was probably due to competition with marine mammals,” the study authors note.

Intriguingly, the closest known relative of C. waiparensis is Crossvallia unienwillia, a Paleocene species that was discovered in Antarctica in 2000. The landmass that would become New Zealand began splitting from Antarctica some 80 million years ago, but during the era of the giant penguins, the regions boasted similarly warm environments.

“When the Crossvallia species were alive, New Zealand and Antarctica were very different from today—Antarctica was covered in forest and both had much warmer climates,” Scofield explains. The similarities between the two species thus highlight New Zealand’s “close connection to the icy continent,” as the Canterbury Museum puts it.

C. waiparensis is also significant because it is the “oldest well-represented giant penguin” known to science, according to the study authors. This in turn suggests that penguins reached a huge size very early in their evolution, a theory that experts had already posited based on the Antarctic specimen. And the study authors believe that the Waipara Greensand site, where C. waiparensis was discovered, holds other secrets to penguins’ ancient history.

“The fossils discovered there have made our understanding of penguin evolution a whole lot clearer,” says Gerald Mayr, study co-author and a curator at the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt. “There’s more to come, too – more fossils which we think represent new species are still awaiting description.”