Humans May Have Been Crafting Stone Tools for 2.6 Million Years

A new study pushes the origins of early human tool-making back by some 10,000 years earlier than previously believed

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/38/21389151-c080-407d-b631-0c27c7651f08/flaked-stone_tools.jpg)

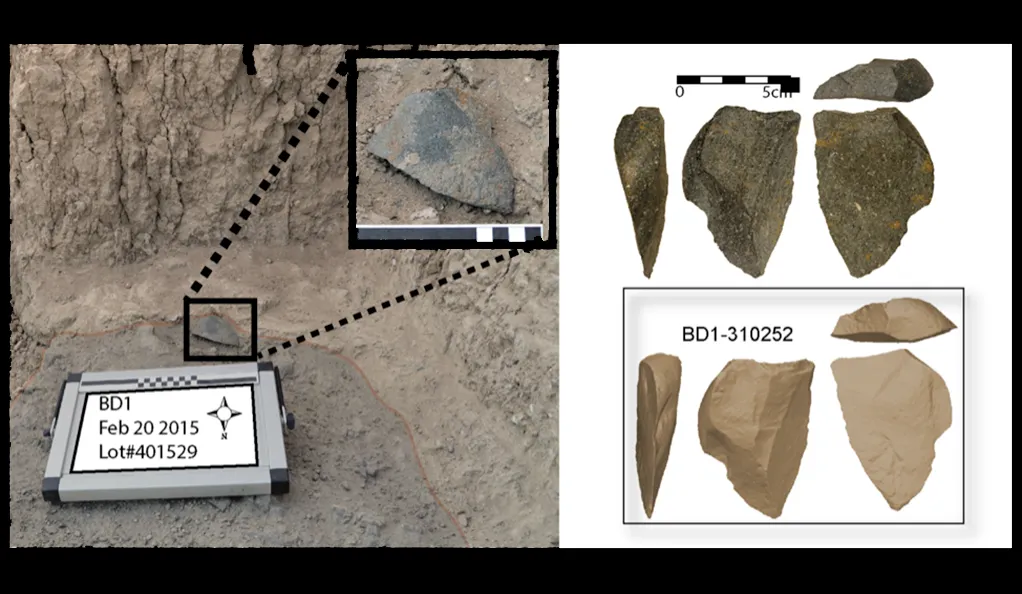

Members of the Homo genus have been making stone tools for at least 2.6 million years, a new study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests. The findings, based on the discovery of a collection of sharp-edged stone artifacts at the Bokol Dora 1 site in Ethiopia’s Afar Basin, push the origins of early human tool-making back by some 10,000 years earlier than previously believed. Additionally, the research suggests that multiple groups of prehistoric humans invented stone tools on separate occasions, adapting increasingly complex techniques in order to best extract resources from their environment.

Although 3.3 million-year-old stone instruments known as "Lomekwian" tools predate the newly described trove, these were likely made by members of early hominin groups such as Australopithecus afarensis rather than members of the Homo genus. Until now, the oldest known Homo tools—dubbed “Oldowan” in honor of the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania where the first examples of such artifacts were found—dated to between 2.55 and 2.58 million years ago. Excavated in Gona, Ethiopia, the sharpened stones are technologically distinct from the more rudimentary Lomekwian tools, which were first catalogued by researchers conducting fieldwork in West Turkana, Kenya, in 2015. Compared to the Oldowan tools found in Gona and now Bokol Dora, the earlier Lomekwian tools are decidedly less advanced.

The Bokol Dora trove, also known as the Ledi-Geraru collection, consists of 327 stone tools likely crafted by striking two rocks together to create sharp edges capable of carving up animals, as Phoebe Weston reports for the Independent. The ancient artifacts were found three miles away from the site where the oldest known Homo fossil, a 2.8 million-year-old jawbone, was unearthed in 2013, pointing toward the tools’ connection with early modern humans rather than ape-like hominins belonging to the Australopithecus genus.

“This is the first time we see people chipping off bits of stone to make tools with an end in mind,” study co-author Kaye Reed, an anthropologist at Arizona State University, tells Weston. “They only took two or three flakes off, and some you can tell weren’t taken off quite right. The latest tools seem slightly different in the way they’re made from other examples.”

Compared with the Gona tools and other Oldowan artifacts, the latest finds are actually rather crude. The instruments have “significantly lower numbers of actual pieces chipped off a cobble than we see in any other assemblage later on,” lead author David Braun of George Washington University explains to New Scientist’s Michael Marshall, adding that it’s possible the humans making them were less skilled than their later counterparts or simply didn’t have a need for extremely sharp tools. Still, the Ledi-Geraru artifacts are distinct enough from the older Lomekwian tools to warrant their classification as Oldowan.

The 2.6 million-year-old implements “have nothing to do whatsoever with what we see later on,” Braun tells Marshall. “It’s possible there are multiple independent inventions of stone as a tool.”

According to Cosmos’ Dyani Lewis, Lomekwian tools are roughly on par with the primitive instruments fashioned by modern primates such as capuchin monkeys. Oldowan tools, on the other hand, reveal a basic understanding of what Braun calls the “physics of where to strike something, and how hard to hit it, and what angles to select.”

“Something changed by 2.6 million years ago, and our ancestors became more accurate and skilled at striking the edge of stones to make tools,” study co-author Will Archer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the University of Cape Town notes in a press release. “The artifacts at BD 1 capture this shift.”

Given the fact that the Ledi-Geraru tools were found alongside the bones of animals, including gazelles and giraffes, the team argues that early humans’ shift toward skilled stone tool-making coincided with a rise in scavenging opportunities. As Science News’ Bruce Bower points out, Homo individuals inhabited open grassland expanses, whereas their earlier Australopithecus ancestors had to contend with dense tree coverage that limited hunting prospects.

Interestingly, the Independent’s Weston writes, the shift from Lomekwian to Oldowan tools appears to be associated with a change in early humans’ teeth. In the statement, Archer explains that processing food with the help of stone tools led to a reduction in the size of our ancestors’ teeth, offering a striking example of how “our technology and biology were intimately intertwined even as early as 2.6 million years ago.”

To date the Ledi-Geraru trove—likely dropped by early humans at the edge of a body of water and subsequently buried for millions of years—researchers drew on volcanic ash found several feet below the excavation site, as well as the magnetic signature of various sediment samples.

But as Bower notes, some scientists have expressed skepticism regarding these dating methods. Paleontologist Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo of Madrid’s Complutense University says a detailed analysis of sediment formation is needed to verify the artifacts’ age, and Yonatan Sahle, an archeologist at Germany’s University of Tübingen, calls it “simply unwarranted” to deem the tools the oldest known Oldowan specimens without conducting further testing.

For now, Braun says, the team must focus on finding additional evidence of stone tools made between 2.6 and 3.3 million years ago. He concludes, “If our hypothesis is correct then we would expect to find some type of continuity in artefact form after 2.6 million years ago, but not prior to this time period. We need to find more sites.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)