Hundreds of Artifacts Looted From Iraq and Afghanistan to Be Repatriated

The trove, currently stored at the British Museum for safekeeping, includes 4th-century Buddhist sculpture fragments and 154 Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/46/f8462e3e-fa61-4fec-bd3e-deb7d2bca4f3/heads-1024x762.jpg)

In 2002, border officials at London’s Heathrow Airport intercepted a pair of wooden crates brought into the country via a flight from Peshawar, Pakistan. Inside, they found a patchwork of 1,500-year-old clay limbs that had been crudely hacked off of sculptures that once stood in Buddhist monasteries in the ancient kingdom of Gandhāra in present-day northwestern Pakistan and northeastern Afghanistan.

Now, 17 years after their recovery, the looted artifacts are returning home. According to a British Museum press release, the 4th-century sculptures—which include nine sculpted heads and one torso—are among a group of 843 heritage objects scheduled to be repatriated from the London institution to the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul.

The stolen items had been seized with the help of the U.K. Border Force, the Metropolitan Police’s Art and Antiquities Unit, and even several private individuals. Following their identification as Afghan artifacts they were ultimately stored at the museum for “safekeeping and recording.”

Speaking with the Guardian’s Mark Brown, curator St. John Simpson describes the sculptural fragments, which were likely targeted during the Taliban’s 2001 iconoclasm spree, as “stunning and “quite outstanding.”

“We’ve returned thousands of objects to Kabul over the years,” he adds, “but this is the first time we’ve been able to work on Buddhist pieces.”

According to the Independent’s Adam Forrest, the nine terracotta heads depict Buddha; meditating bodhisattvas, or individuals on the path of enlightenment; a bald monk; and three larger figures, one of whom may be Vajrapani, Buddha’s spiritual guide. The Evening Standard’s Robert Dex further identifies the stone torso as belonging to a statue of a Buddhist holy man.

As Brown writes, the sculptures speak to Buddhism’s short-lived influence in what is now Afghanistan, where the religion thrived between roughly the 4th and 8th centuries.

“The return of any object which has been illegally trafficked is hugely important symbolically,” Simpson tells Brown. “But these pieces will form one of the largest groups of Buddhist art to be returned to the Kabul museum. When you think [of] what Kabul has been through since the 1990s, culminating in the atrocity of Bamiyan”—in 2001, the Taliban blew up an iconic set of monumental 6th-century statues known as the Bamiyan Buddhas—“this is a huge event.”

With the National Museum of Afghanistan's blessing, some of the Buddhist sculptures will go on view at the British Museum before being transferred to officials at the Afghanistan embassy in London. Upon their return to Kabul, they will be exhibited at the National Museum.

Per the museum press release, artifacts set for repatriation also include examples of the 1st-century Begram Ivories, a Buddha statue dating to the 2nd or 3rd century, Bronze Age cosmetic flasks, medieval Islamic coins, pottery, stone bowls, and “other minor items of mixed date and materials.”

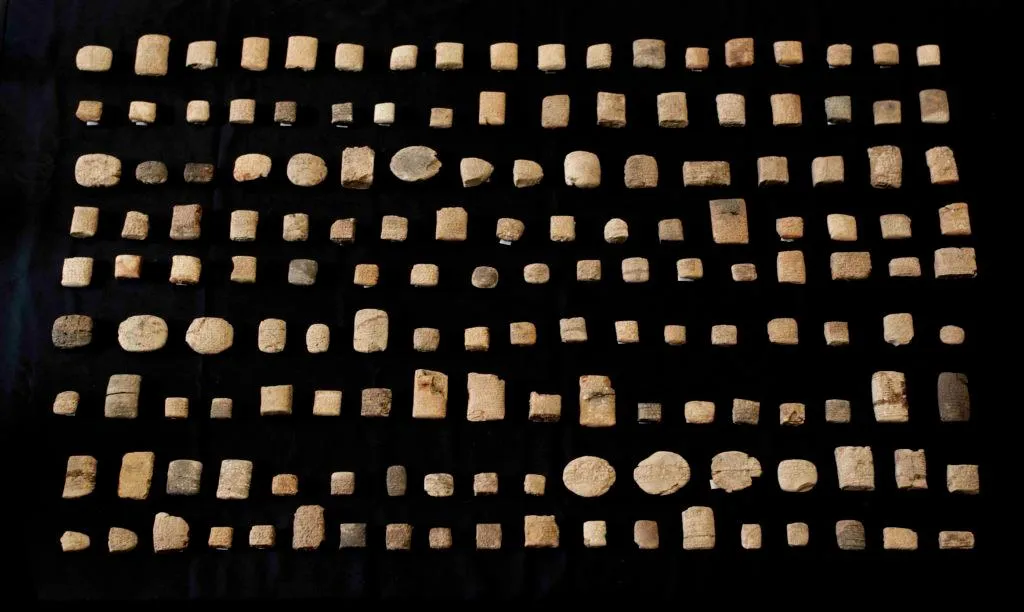

Separately, Naomi Rea reports for artnet News, the British Museum will return a set of 154 Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad. Seized in 2011, the clay texts date to the mid-3rd century B.C. and describe administrative operations in the lost city of Irisagrig. With the permission of the National Museum of Iraq, a selection of the artifacts will also go on view at the British Museum before returning home.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)