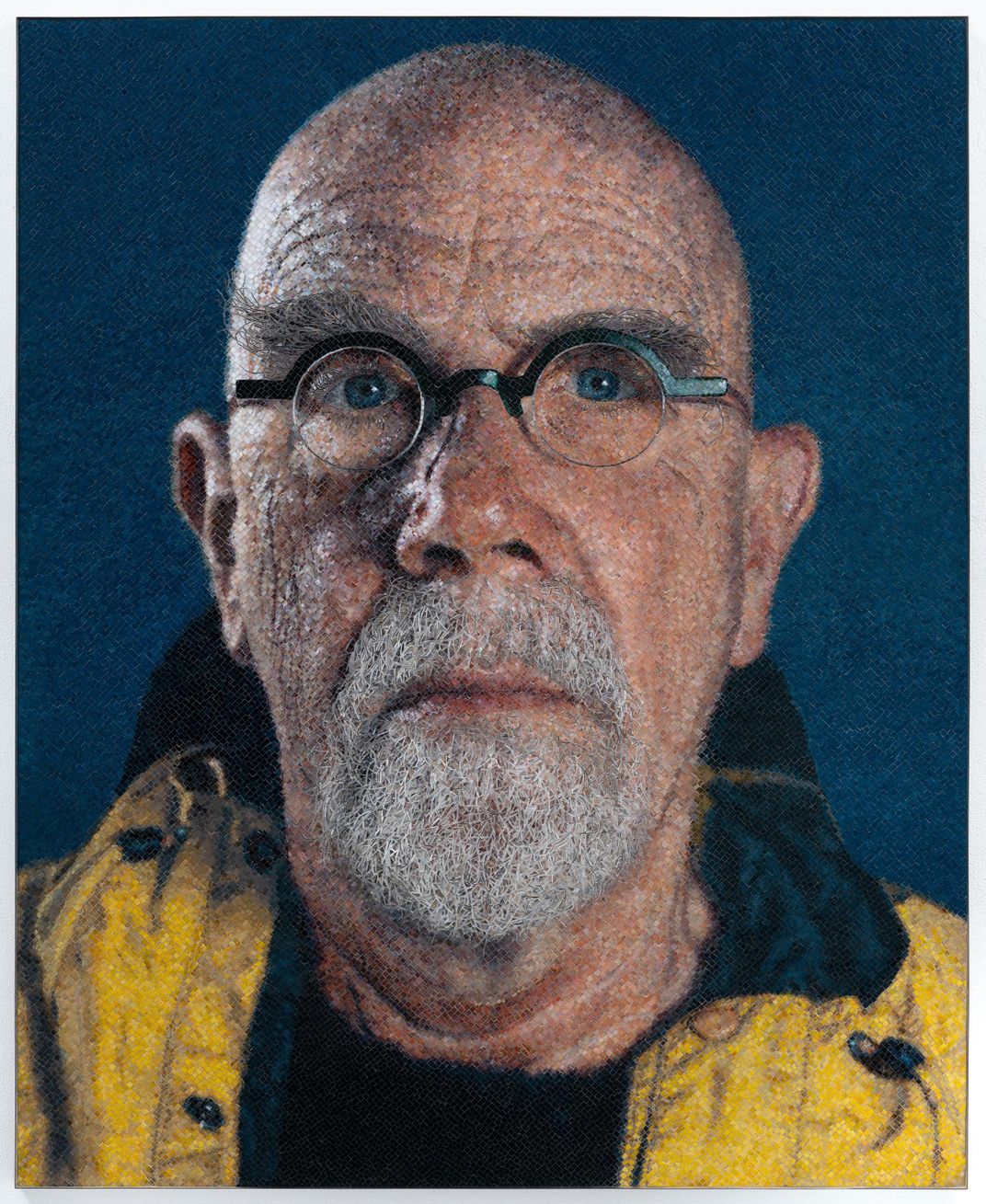

Chuck Close, Artist Whose Photorealist Portraits Captivated America, Dies at 81

The painter, who faced accusations of sexual harassment later in life, continuously changed his artistic style

:focal(392x201:393x202)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/4f/404f6027-ed97-4607-9e6d-7c7c8560732e/chuck_close.jpg)

Chuck Close, the acclaimed American artist known for his stunning photorealist portraits, died last Thursday at age 81.

As Ken Johnson and Robin Pogrebin report for the New York Times, the painter died of congestive heart failure in a hospital in Oceanside, New York. He’d gained fame in the 1970s and ’80s by creating larger-than-life portraits of himself, his family and his friends, but faced accusations of sexual harassment later in his career.

“Chuck Close was a groundbreaking artist who moved the genre of portraiture in bold new directions,” says Dorothy Moss, curator of painting and sculpture at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, to Smithsonian magazine. “He was a good friend of the [gallery] for decades and his work paved the way for artists and art historians to think broadly about portraiture’s relevance and impact in the contemporary world.”

Born in Monroe, Washington, in 1940, Close struggled with dyslexia as a child and used art as an outlet to express himself. Per a 1998 profile by the New York Times’ Deborah Solomon, the burgeoning artist tirelessly honed his craft, staying up late and inspecting magazine covers with a magnifying glass to “figure out how paintings got made.”

Close’s hard work paid off, enabling him to develop skills across a number of artistic disciplines, including photography, printmaking and weaving. Though he eventually won acclaim for his hyperrealist portraits, he spent his college years emulating the work of Abstract Expressionists like Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning.

While teaching at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in the late 1960s, Close developed his signature style: “breaking down photographs into intricate grids and then blowing them up, reproducing them square by painstaking square onto oversized canvases,” according to Petra Mayer of NPR.

Redefining figuration in an era dominated by abstraction, “Close devised an art [style] that was smart, challenging, avant-garde, uncanny, insistent, implacable, but infinitely accessible and even user-friendly,” writes critic Jerry Saltz for Vulture.

Highlights of Close’s oeuvre include his iconic Big Self-Portrait (1967–68), in which the artist stares at the viewer through thick-rimmed glasses while dangling a cigarette from his mouth, and Phil (1969), a black-and-white depiction of the composer Philip Glass. The Smithsonian American Art Museum houses a number of Close’s works, including Phil III (1982) and Self Portrait (2000).

In 1988, a spinal artery collapse left Close almost completely paralyzed, forcing him to adopt a radically different approach to art. He taught himself how to paint again by using Velcro to affix brushes to his wrists, embracing a looser, more abstract style that many critics actually preferred to his earlier work.

“My entire life is held together with Velcro,” Close reflected in the 1998 Times profile.

No reflection on Close’s legacy can be complete without acknowledging the accusations of sexual harassment that dogged him later in life. As Pogrebin reported for the New York Times in 2017, multiple women who had previously posed for Close came forward with accounts of his inappropriate behavior. In response to these claims, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. canceled an exhibition of Close’s paintings, and the artist became “persona non grata in many parts of the art world,” per the Times’ Roberta Smith.

“If I embarrassed anyone or made them feel uncomfortable, I am truly sorry, I didn’t mean to,” Close told the Times in 2017. “I acknowledge having a dirty mouth, but we’re all adults.”

In 2013, Close was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Two years later, this diagnosis was updated to frontotemporal dementia—a condition that can lead to “dramatic changes in … personality,” as well as “socially inappropriate, impulsive or emotionally indifferent behavior,” according to the Mayo Clinic.

“[Close] was very disinhibited and did inappropriate things, which were part of his underlying medical condition,” the artist’s neurologist, Thomas M. Wisniewski, tells the Times. “Frontotemporal dementia affects executive function. It’s like a patient having a lobotomy—it destroys that part of the brain that governs behavior and inhibits base instincts.”

The National Portrait Gallery, which houses several works by Close, reflected on the artist’s passing in an “In Memoriam.”

“The National Portrait Gallery acknowledges that, in 2017, several women accused Chuck Close of sexual harassment, though no charges were brought against him,” the museum said. “[We recognize] the positive and negative impacts that individuals represented in our collections have had on history.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)