Infants Can See Things That Adults Cannot

Over time, our brains start filtering out details deemed unimportant

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/04/7c/047c0b58-e60e-4b52-bccc-9fc51b83f6dc/42-72940312.jpg)

When babies are just three to four months old, they can pick out image differences that adults never notice. But after the age of five months, the infants lose their super-sight abilities, reports Susana Martinez-Conde for Scientific American.

Don't get too jealous of the superior discrimination that infants have however: The reason adults—or even babies older than about eight months—don't have it is because over time, our brains learn what differences are important to notice.

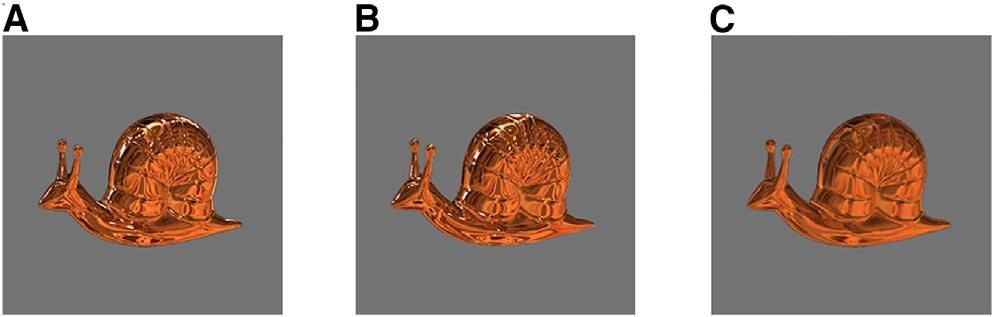

For example, when adults look at the images of a snail (below) they typically say that glossy snail A and and glossy snail B are the most similar. The matte-looking snail C seems to be the outlier. But a baby can tell that snail B and snail C are actually more similar. Though it is hard for adults to see, snail A stands out from the others—the surface of the snail reflects very different lighting conditions. Babies are more sensitive to that seemingly trivial image difference.

"[W]e learn to ignore certain types of differences so that we can recognize the same object as unchanging in many varied scenarios," writes Martinez-Conde.

Researchers based in Tokyo, Japan explored this ability of very young children by testing 42 infants between the ages of three to eight months old. Since these babies can't yet talk, the researchers tracked their perception of images based on how long the babies stared at each image.

Previous research has shown that when a baby sees something they consider new, they stare longer; objects they are familiar with only merit a passing glance.

The time differences in gaze showed that the three and four month-old babies noticed the the difference in pixel intensity and were less impressed with differences in the surfaces—whether the images were glossy or matte, that is. But by the time the infants were seven to eight months old, their vision was closer to that of adults, and they could no longer see the pixel difference. The team published their findings in the journal Current Biology.

Scientists call this type of change a perceptual narrowing, meaning that attention focuses in and people can miss out on certain differences. It's a normal part of the development of the brain and vision.

Another study showed that babies younger than six months of age could recognize different monkeys by their faces alone, whereas adults and even nine-month-olds could only recognize human faces.

The loss of sensitivity isn't anything to mourn, however. The babies are keying in to a difference that amounts to light changes, not a change in the object itself. Adults instead recognize that this is the same snail, even if the enviroment around it has shifted in some way. Ignoring that relatively meaningless difference is a way that humans "tune our perception to our environment, allowing us to navigate it efficiently and successfully," Martinez-Conde writes for Scientific American. "[E]ven if it left a large portion of reality forever outside our reach," she adds.

In other words, babies might see things that adults can't, but adults more fully understand what they do see.