The Inventor of the Telegraph Was Also America’s First Photographer

The daguerreotype craze took over New York in the mid-nineteenth century

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/aa/63aa861a-57c9-44a3-af3a-b620528fdd72/3c10084u.jpg)

On this day in 1839, the French Academy of Sciences revealed the results of many years of work by Louis Daguerre: a new kind of image called —you guessed it—the daguerreotype.

Daguerre’s first picture was a (today somewhat creepy-looking) still-life of an artist’s studio, complete with carved store cherubs and other sketchable items. But the meaning of his invention was immediately evident: being able to reproduce an accurate, lasting picture of something in minutes, was revolutionary.

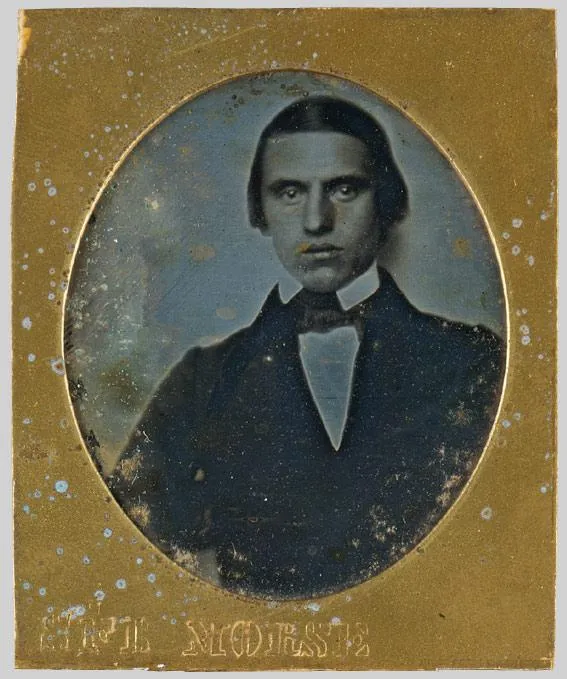

One of the first to actually learn from Daguerre was inventor Samuel Morse, whose own daguerreotype portrait still exists. He’s responsible for the telegraph and Morse code, and was also a skilled painter, writes David Lindsay for PBS.

“Morse happened to be in Paris just as the daguerreotype craze was blooming,” he writes. The inventor and artist met with Daguerre twice in March 1839. On viewing one of Daguerre's images, the level of detail moved him to declare that the work was "Rembrandt perfected," writes Lindsay.

Back in New York, he set himself up to teach others how to make the images. His pupils “came to include Mathew Brady, whose Civil War photographs achieved lasting fame, and Edward Anthony,” Lindsay writes.

But though Samuel Morse arguably brought the daguerreotype craze to America, only one image that he took survives. The unknown sitter “clearly strains to keep his eyes open during the long, twenty-to-thirty minute exposure,” writes the Met.

Morse's daguerreotype camera also survives, and is owned by The National Museum of American History.

Daguerre didn’t publicly reveal how he made daguerreotypes until August of 1839. Initially, he hoped to sell it by subscription, writes Randy Alfred for Wired. But after the Academy lobbied the government, he writes, Daguerre and Isidore Niepce, the widow of his deceased collaborator Nicephore Niepce, received pensions so they could afford to take the process open-source.

It was the beginning of a daguerreotype craze on both sides of the Atlantic. By 1841, Lindsay writes, New York City had 100 studios, “each set up after the fashion of elegant parlors.” And by 1853, he writes, “there were 37 parlors on Broadway alone, and on the banks of the Hudson, a town one mile south of Newburgh had been named Daguerreville.”

By 1860, though, the time of the daguerreotype was over. Although its speed made it a viable method for doing commercial photography, daguerreotypes fixed an image to a single metal plate, writes Tony Long for Wired. Because of this, there were no “negatives” from which a second copy could be made. It was replaced by the albumen print, Long writes, which was the first commercially available way to produce photographs on paper, rather than on metal.