Follow Dante Into Purgatory With Online Exhibition of ‘Divine Comedy’ Drawings

The Uffizi Gallery’s digital show features 88 illustrations by 16th-century artist Federico Zuccari

:focal(750x502:751x503)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/bf/1dbf753f-2c6e-44f0-9f04-5a7b85d0c6bf/dante_domenico_di_michelino_duomo_florence.jpg)

For centuries, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy—a lengthy narrative poem describing the author’s vision of the afterlife—has earned plaudits as one of the greatest works of Western literature, inspiring esteemed authors and artists from Geoffrey Chaucer to T.S. Eliot, Sandro Botticelli and William Blake.

In honor of the 700th anniversary of the Italian poet’s death, Florence’s Uffizi Gallery is hosting a free, online exhibition of 88 drawings depicting the seminal work. Titled “To See the Stars Again”—a reference to the last line of Inferno, the opening section of The Divine Comedy—the show features illustrations by artist Federico Zuccari, who created the works while living in Spain between 1586 and 1588.

As the Associated Press reports, the fragile drawings, which entered the Uffizi’s collections in 1738, have only been shown publicly twice before: in Dante’s hometown of Florence in 1865, the 600th anniversary of his birth, and in Abruzzo, a region in southern Italy, during a 1993 exhibition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/2b/ea2b953a-cd0c-4cea-8e00-a79267b55639/960x0.jpg)

“So far, these beautiful drawings have been seen by [only] a few scholars,” the Uffizi’s director, Eike Schmidt, tells the Art Newspaper’s Gareth Harris. “[This is] precious material not only for those doing research but also for those who are passionate about Dante’s work and interested in following, as Alighieri says, [ideas around] virtue and knowledge.”

According to the Uffizi, the online exhibition portal preserves Zuccari’s handwritten notes, which he penned on the backs of the drawings. Artworks are presented alongside the cantos, or sections, they illustrate, as well as scholarly commentary.

Often described as the father of the Italian language, Dante was born in Florence in 1265 and died in Ravenna in 1321. His Divine Comedy is divided into three sections that follow the poet as he travels through hell, purgatory and heaven. Of the 88 drawings in the exhibition, 28 portray hell, while 49 depict purgatory and 11 show heaven.

Writing for Forbes, Matthew Carey Salyer deems Zuccari’s focus on the poem’s middle section, Purgatorio, “unusual.”

The purgatory drawings “involve a change in medium, abandoning the series’ pencilwork in favor of a pen and watercolor technique,” he adds. “The aesthetic shift makes sense. In Dante’s cosmology, Purgatory is a temporal condition, one in which souls are still capable of change and development after death.”

One highlight of the exhibition is Zuccari’s depiction of Lucifer, who is shown as a monster with three faces—likenesses of Judas, who deceived Jesus Christ, and Brutus and Cassius, who betrayed Julius Caesar. The symmetrical sketch somewhat resembles Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, albeit with a hellish twist, notes Forbes.

“The observer’s imagination is forced to recreate the terrible features of the Antichrist and the lake of ice in which he has sunk up to his chest,” the accompanying exhibition text reads, per Google Translate.

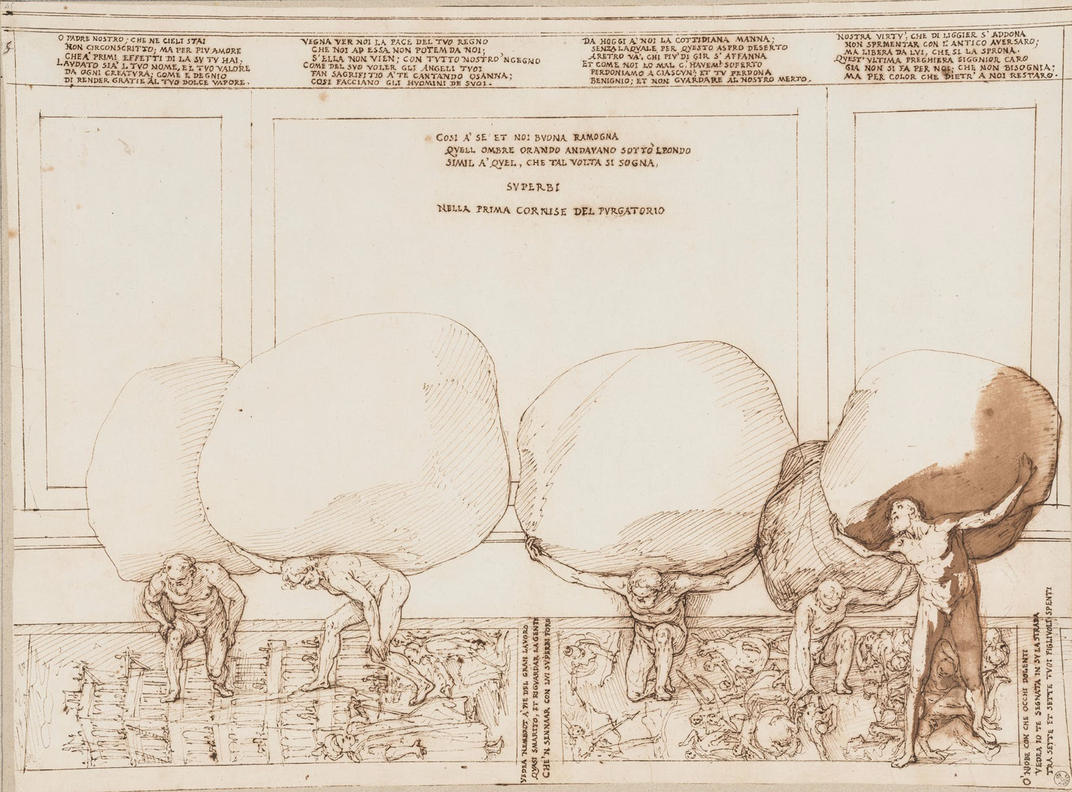

Other pieces, like First Frame: Prayer of the Proud, illustrate punishments that people are forced to undergo in purgatory. The four men shown carry enormous boulders on their shoulders; examples of pride—like the construction of the tower of Babel—and its consequences—the killing of Niobe’s sons—appear in the background.

Born in Italy in 1540, Zuccari was a distinguished late Mannerist painter. (The artistic movement focused on creating elongated, stylized figures rather than realistic depictions.) He created works for Popes Pius IV and Gregory XIII, painted portraits of Elizabeth I and her court, and helped design Spanish king Philip II’s citadel-like El Escorial.

Zuccari completed his Divine Comedy drawings while working at Philip’s court. Following his death in 1609, the illustrations came into the possession first of the noble Orsini family and later the Medici family, which donated them to the Uffizi in 1738.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)