This Jane Austen Letter Highlights the Horrors of 19th-Century Dentistry

The missive, penned after the author accompanied her nieces on a visit to the dentist, will be up for auction later this month

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/cb/8dcb07d9-d9b5-4baa-9f9b-4f53e1f905e9/image.jpeg)

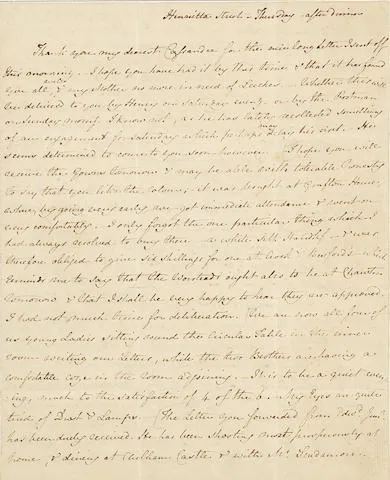

Visiting the dentist is one of life’s necessary evils. It’s often uncomfortable, sometimes a little painful, and, once you reach adulthood, no longer rewarded with a sticker. But modern-day dental treatments are a downright picnic compared to the procedures patients endured in centuries past. Take, for example, the dental visit experienced by Jane Austen, who recorded a rather horrifying day at the dentist in an 1813 letter to her sister Cassandra.

By the time Austen sat down to compose the missive, she and her family members had settled in comfortably for the evening. The author painted a vivid scene for her sister, explaining, “We are now all four of us young Ladies sitting round the Circular Table in the inner room writing our Letters, while the two Brothers are having a comfortable coze” —or chat—“in the room adjoining.” Earlier in the day, however, Austen noted that she had accompanied her three nieces on a visit to the dentist (one Mr. Spence) and was rather perturbed by what she saw.

“The poor Girls & their Teeth!” she wrote. “[W]e were a whole hour at Spence’s, & Lizzy’s were filed & lamented over again & poor Marianne had two taken out after all. ... We heard each of the two sharp hasty screams.”

The author, who had published Pride and Prejudice two years earlier, was particularly unsettled by what she viewed as unnecessary treatment inflicted upon her favorite niece, Fanny.

“Fanny’s teeth were cleaned too—& pretty as they are,” Austen added, “Spence found something to do to them, putting in gold & talking gravely—& making a considerable point of seeing her again before winter.”

The dentist, she concluded, “must be a Lover of Teeth & Money & Mischief.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/60/2b/602be401-e19e-403a-8ee4-6336748319e2/484px-jane_austen_coloured_version.jpg)

This letter, tinged with Austen’s signature sardonic wit, will be up for auction next week. It is expected to fetch between $80,000 and $120,000—no small price, but plausible given the fact that the note is a significant relic. Only 161 of the estimated 3,000-odd letters Austen wrote during her lifetime survive; Cassandra and other members of the author’s family destroyed most of them following her death, perhaps in an effort to stop any embarrassing personal details from coming to light. The letter also offers insights on dental procedures during England’s Regency period—procedures that, as Austen makes clear, were not particularly pleasant.

Dentistry only started to emerge as a distinct profession after French physician Pierre Fauchard, known as the “Father of Modern Dentistry,” published a comprehensive scientific treatise on the practice. Prior to Fauchard’s 1728 intervention, so-called “barber surgeons” tended to Europeans’ dental ailments, performing treatments ranging from extracting teeth to leeching and giving enemas. Other advancements—including the use of nitrous oxide as an anesthetic—arrived during the 19th century.

In Austen’s day, Jessica Leigh Hester writes for Atlas Obscura, the field of dentistry was still “painfully unstandardized,” and dental problems ran rampant.

According to the Jane Austen Center, oral hygiene was “not a well advocated practice” during the author’s lifetime. Simple tools such as toothpicks and toothbrushes made with hog’s hair were available, but as Lindsey Fitzharris reports for the Guardian, they “often caused more problems than they prevented.” The same can be said of the pulverized charcoal, salt, brick and chalk used as toothpaste.

When cavities inevitably arose, dentists could do little except extract the problematic tooth, performing a Little Shop of Horrors-esque procedure with instruments known as “pelicans” and “keys.”

“The pelican was a brutal instrument with a pad or bolster, which was placed on the side of the gum below the tooth to be extracted and a beak or claw which engaged the opposite side,” the Jane Austen Center explains. “A downward twist of the handle tore the tooth out of the mouth. The key was similar, but had a handle similar to that of a corkscrew and enabled the instrument to be used more comfortably from the front of the mouth instead of the side.”

Those with sufficient funds might fill gaps in their teeth with porcelain from willing donors in need of cash, but Fitzharris notes that replacement teeth were also pulled from dead bodies. Dentures, which were often ill-fitting and uncomfortable, came from similarly disturbing sources: George Washington—who, contrary to popular legend, did not boast false teeth made of wood—likely relied on dentures made from various materials, including metal alloys, cow and horse teeth, and human teeth.

“[He] probably gave his inaugural speech with teeth that were from people who were enslaved," Kathryn Gehred, a research specialist at the University of Virginia, told Live Science’s Stephanie Pappas in 2018. “It's grim.”

Filing, as experienced by Austen’s niece Lizzy during her trip to the dentist, was used to smooth out uneven teeth. Some believed it could also help prevent cavities. In reality, Rachel Bairsto, head of museum services at the British Dental Association Museum, tells Hester, “Overzealous filing [threatened to] make the teeth more sensitive.”

All of this is to say that bad, missing and aching teeth were simply a fact of life in the centuries before modern dentistry. So, when you find yourself dreading your next dental appointment, perhaps think of poor Lizzy, Marianne and Fanny. By comparison, you might consider yourself lucky.