National Gallery of Art Acquires Its First Painting by a Native American Artist

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s work addresses questions of identity and appropriation

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d3/de/d3de5016-de45-4617-ac20-9b0afb30747b/smith.png)

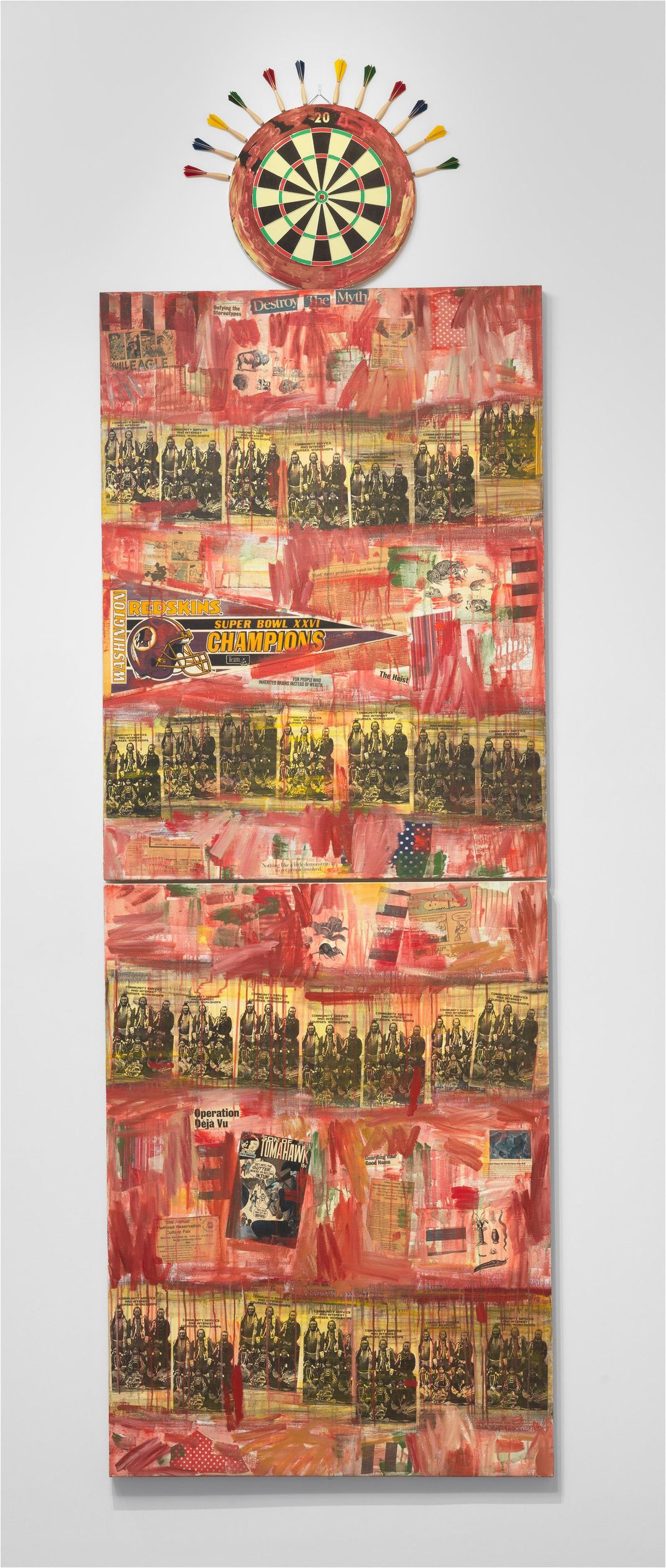

The National Gallery of Art has made a landmark addition to its collections: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s I See Red: Target (1992), an 11-foot-tall mixed media work on canvas. The acquisition—the first major painting by a Native American artist to enter the museum’s collections, according to a statement—comes nearly eight decades after the Washington, D.C. cultural institution opened its doors in 1941.

“The staff and I take very seriously our public mission and the mandate to serve the nation,” the gallery’s director, Kaywin Feldman, tells the Washington Post’s Peggy McGlone. “In order to serve the nation in its broadest sense, we have to attract and reflect [its] diversity.”

Born on Montana’s Flathead Reservation in 1940, Smith is an enrolled member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Over the course of her 40-year career, she has created paintings, prints and mixed-media collages that critique and riff on themes of identity and history, particularly in relation to the representation of Native Americans in popular culture.

As the artist tells Kathaleen Roberts of the Albuquerque Journal, she is shocked to be the first Native American artist whose work enters the gallery’s collections.

“Why isn’t [it] Fritz Scholder or R.C. Gorman or somebody I would have expected?” Smith says. “On the one hand, it’s joyful; we’ve broken that buckskin ceiling. On the other, it’s stunning that this museum hasn’t purchased a piece of Native American art [before].”

Speaking with Marketplace’s Amy Scott, Kathleen Ash-Milby, curator of Native American art at the Portland Art Museum, adds, “What is really jarring specifically about the National Gallery is that it is supposed to represent the art of the nation, and Native American art is a big part of that,”

Smith created I See Red: Target as part of a series responding to the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the Americas. The work consists of two canvases topped by a circular dartboard “head.” The motif references Jasper Johns’ Target (1958), which now hangs across the room from Smith’s painting. Per the statement, the artist arranged the board’s darts in a formation that alludes to a headdress.

The “body” of the work consists of a mixed-media collage featuring bright red paint, clippings from newspapers including the Char-Koosta News (the Flathead Reservation’s local outlet) and a comic book cover. Its “stain-like drips of bloodred paint” evoke a sense of rage compounded by the work’s layered references to historical appropriation of Native American imagery, according to the statement.

I See Red is about “Indians being used as mascots,” the artist explains to the Journal. “It’s about Native Americans being used as commodities.”

Near the top of the work, Smith includes a pennant emblazoned with the racist name of Washington D.C.’s football team—an inclusion that feels particularly relevant today, as the team faces increasing pressure to change its name amid widespread anti-racism protests across the United States.

The National Gallery houses 24 other works by Native American artists, including photographs and works on paper by Sally Larsen, Victor Masayesva Jr. and Kay WalkingStick, in its collections. But the paper holdings are very fragile and have never actually been exhibited at the museum, writes budget and administrative coordinator Shana Condill in a blog post.

“I think it’s fair to say that Native artists have not been well represented at the Gallery,” she adds.

Condill, a citizen of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, had the chance to examine I See Red up close before the museum closed its doors in March due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It hangs in the East Building’s Pop Art galleries alongside works by Jasper Johns and Andy Warhol, reports Artsy.

“Reaching up to the ceiling, the scale and the intense redness of the painting immediately catches your attention,” says Condill. “ … It’s like a punch, but it draws you in. And then you notice all the pieces, the scraps of newspaper, the comic book. It’s clear—the topic is racism. But the painting is full of discoveries for you to make—the artist is inviting a conversation.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)