Jurassic-Era Insect Looks Just Like a Modern Butterfly

Jurassic “butterflies” helped pollinate ancient plants millions of years before the butterfly even existed

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/98/94/98948007-d2bd-4cc0-af9e-da693c707e7d/kalligramma-cover-graphic-v1-2-17-15_6.png)

During the Jurassic period, which ended roughly 145 million years ago, a little insect flitted about sipping nectar and pollinating plants. It might have looked and behaved strikingly like a butterfly, but this long-extinct lacewing existed 40 to 85 million years before the earliest butterflies ever stretched their wings.

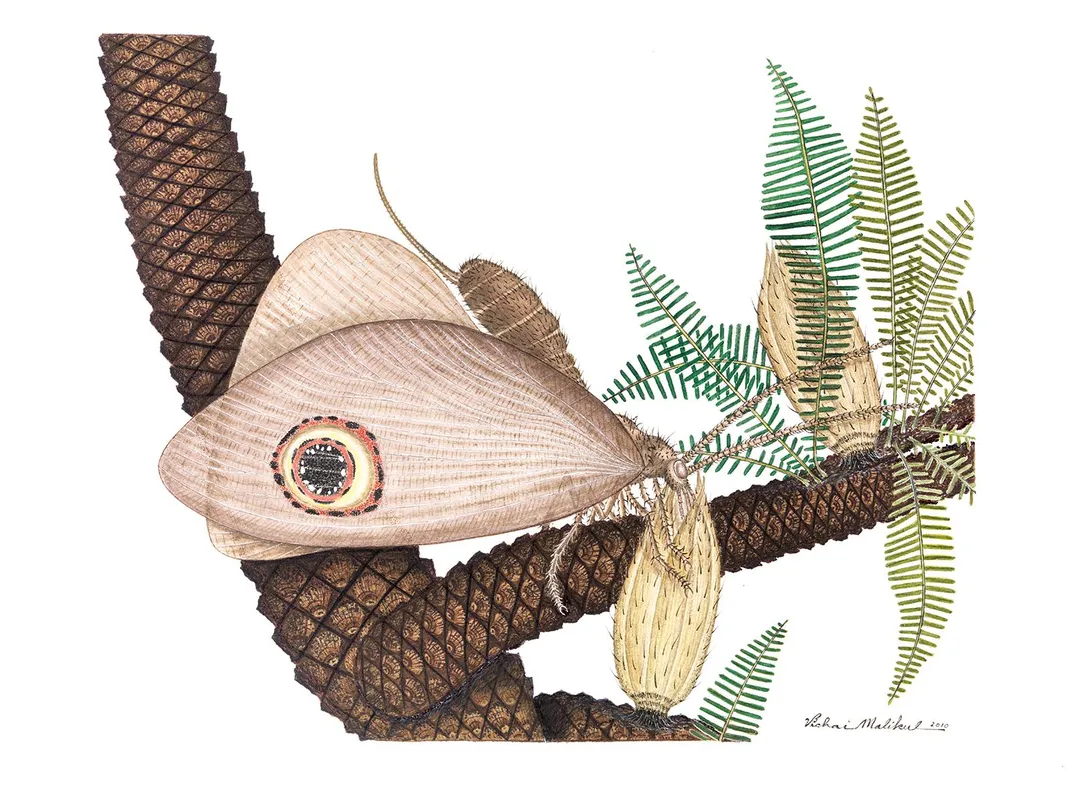

When you put a picture of a kalligrammatid fossil next to a modern owl butterfly, the resemblance is uncanny: Both bugs have large wings decorated with a single spot that looks like an eye. These ancient insects may have even pollinated distant relatives of pine trees and cycads as they sipped on the plant’s nectar, Nala Rogers writes for Science magazine. But while they may look similar, the kalligrammatid lacewings are more closely related to insects like snakeflies and mayflies, according to a new study published this week in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Because the kalligrammatid lacewings were relatively fragile insects, few fossils were preserved well enough for a detailed analysis. However, a team of scientists, including several from the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, examined a set of 20 well-preserved fossils uncovered in ancient lakes in northeastern China and discovered the remarkable resemblance.

“Upon examining these new fossils, however, we’ve unraveled a surprisingly wide array of physical and ecological similarities between the fossil species and modern butterflies, which shared a common ancestor 320 million years ago,” Indiana University paleobotanist David Dilcher said in a statement.

The similarities go beyond just coloration and feeding habits, Conrad Labandeira, paleobiologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, explains to John Barrat of Smithsonian Science News. “If you look at a modern butterfly wing at very high magnification, the colors that you see are actually determined by very small scales that are pigmented differently,” he says. “It looks like kalligrammatids had these same type of wing scales.”

Convergent evolution, a phenomenon where two distantly related animals evolve similar physical features, is not uncommon. However, many think of it more in geographical terms—development of a feature that can help a creature survive in a particular type of habitat.

In this case, instead of being separated by distance, butterflies and kalligrammatids were separated by millions of years, demonstrating that convergent evolution can happen even across massive timescales, Becky Ferreira writes for Motherboard.

While the kalligrammatid may look just like a butterfly, there are some differences between the two bugs. For one, while kalligrammatids might have had similar tastes in food as their distant cousins, they didn’t sip on nectar from flowers. In fact, the first flowers didn’t even appear until about 100 million years ago.

Though the kalligrammatid lacewings used similar tube-shaped mouthparts to feed, analysis of microscopic flecks of pollen preserved on the faces of the fossilized insects showed that they likely fed on an extinct seed plant called a “bennettitale.” They likely used that tube-shaped protrusion to probe the bennettitale insides for a taste of nectar, Rogers writes.

Evolution may be an innovative process, but this example just goes to show how some animals can arise to fill a niche left behind by another.

“If it worked once, why not try it again,” Dilcher said.