Kerry James Marshall’s New Paintings Consider Blackness and Audubon’s Legacy

New series explores black erasure in art and John James Audubon’s own racial identity

:focal(804x329:805x330)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/22/81220f61-46a4-4a38-bbb4-92ceffda5088/crow.jpg)

A new series by Kerry James Marshall offers a vivid reimagination of blackness in the Western canon of art and ecology.

In two works, Marshall plays on John James Audobon’s seminal Birds of America. Audubon’s collection of 435 watercolors, created in 1827, is considered foundational as both a source of ecological knowledge and artistry.

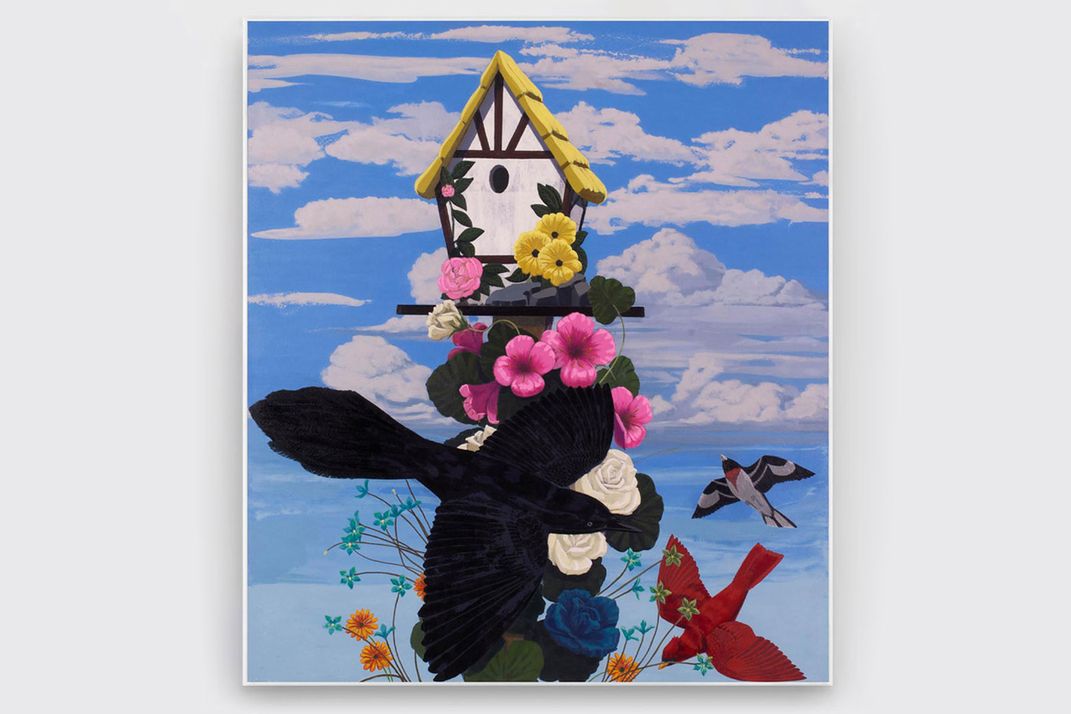

One memorable encounter with a crow a decade ago and Marshall’s own love of birding inspired the paintings. The works, Black and part Black Birds in America: (Crow, Goldfinch) and Black and part Black Birds in America: (Grackle, Cardinal & Rose-breasted Grosbeak), debuted in the David Zwirner Gallery online viewing rooms last week. They are the beginning of a series in which Marshall plans to continue developing.

In one, a crow perches precariously on a birdhouse that is too small to accommodate it. In the other, a black grackle flies past a brightly colored arrangement of flowers, crossing paths with a cardinal and grosbeak. Both images include colorful birds with dark markings—“part Black Birds.” While these other birds fit naturally into the birdhouse scene, the grackle and crow seem awkward in the same space.

“There’s a disconnect between the house that’s built and the birds,” Marshall tells Ted Loss of the New York Times. The image considers “the pecking order.”

According to the gallery overview, Marshall uses chromatic black paint, which appears as a pure black though it contains various different pigments.

“I have to be able to show that it’s not just a silhouette; it has volume, it breathes,” Marshall tells the New York Times. “And so I had to figure out how to make that happen but not diminish the fundamental blackness of the thing.”

From a young age, Marshall was interested in birding and Audubon’s work in particular.

Audubon was born Jean Rabin in Haiti in 1785. His father was a French plantation owner and his mother a chambermaid. There is a theory that his mother was a biracial Creole woman, though some scholars have rejected this idea, reports Katherine Keener of Art Critique.

He moved to the United States at 18 years old and changed his name to John James Audubon in 1785, obscuring his foreignness. To advance his work, he befriended presidents James Harrison and Andrew Jackson, and his work inspired Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation efforts. At the time, slavery remained legal and efforts to classify people and animals were popular among pseudo-scientists. In his series, Marshall highlights parallels between the categorization of people and animals by race or species both in Jefferson’s time and today.

In the first of a series exploring the Audubon’s legacy, historian Gregory Nobles writes that Audubon himself was an enslaver and staunch anti-abolitionist. To create his famous Birds of America, Audubon relied on the labor of enslaved black workers and Native Americans to collect specimens and gather ornithological information, though he took pains to distance himself from them socially and racially. He is also known to have raided Native American graves, reports Hannah Thomasy for Undark.

According to Nobles, Audubon described his mother as a wealthy “lady of Spanish extraction” who was killed by a Black Haitian in the revolution, though neither story is true.

“In an American society where whiteness proved (and still proves) the safest form of social identity, what more could Audubon need?” Nobles writes.

Still, the theory of his racially-mixed descent inspired Marshall and others to consider his role as a “part Black” artist. Artist David Driskell included some of Audubon’s works in his 1976 exhibition “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950.” Marshall viewed the exhibit and claims it contributed to his intrigue with Audubon in following decades.

“His paintings have been filled with birds all along,” she added. “If you wanted to go birding in a Kerry James Marshall show, you could. People were paying so much attention to the human figure in his work, the birds may have gone unexamined,” Helen Molesworth, who was co-organizer of a 2016-17 retrospective of Marshall’s work, tells the New York Times.

Marshall began painting the new series in March, as coronavirus cases in the U.S. began to surge. In May, a white woman threatened to call the police on Christian Cooper, a black man and director of the New York City Audubon. Marshall tells the New York Times he felt an affinity to Cooper as a fellow birder.

This new series contributes to a reconsideration of the role of blackness in the Western canon of art and ecology, in his career-long effort to build a “counter-archive” to black invisibility.

“None of us works in isolation. Nothing we do is disconnected from the social, political, economic, and cultural histories that trail behind us. The value of what we produce is determined by comparison with and in contrast to what our fellow citizens find engaging,” Marshall says in a David Zwirner statement.

The works are available online at the David Zwirner Gallery through August 30, 2020.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_1578_copy_copy.jpg)