Komodo Dragons Have Skin That Looks Like Chain Mail

CT scans show layered bone covers the adult reptile’s body, likely to protect them when fighting for mates and food

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e0/bf/e0bfe715-ff64-49f3-bed8-7b692d4f0d68/komodo_ct_orange.jpg)

No, they don’t breathe fire, but Komodo dragons do have something medieval about them: skin that looks like chain mail, new research shows.

Researchers have known about the bony bits since the dragon was first identified by western scientists in 1910. The armor protected the animals them from the get go; the “osteoderms” as the bone fragments are called, made komodo skin unsuitable for making leather, saving the animals from commercial exploitation. Osteoderms are found in other lizard species as well, but zoologists puzzled over the arrangement and purpose of Komodos’ bony armor.

Komodo dragons are the largest lizard species in the world. The animals, which live on a handful of Indonesian islands, are the top predators in tropical savannahs, where the 150-pound beasts hunt other lizards, rodents, monkeys, deer and even young water buffalo. They have serrated teeth and mobile jaws perfect for gulping down huge chunks of flesh. They’re also one of few reptiles with a poisonous bite, which immobilizes and eventually kills their prey.

If they’re so tough, then why do they need skin that looks like it could withstand the blade of a sword?

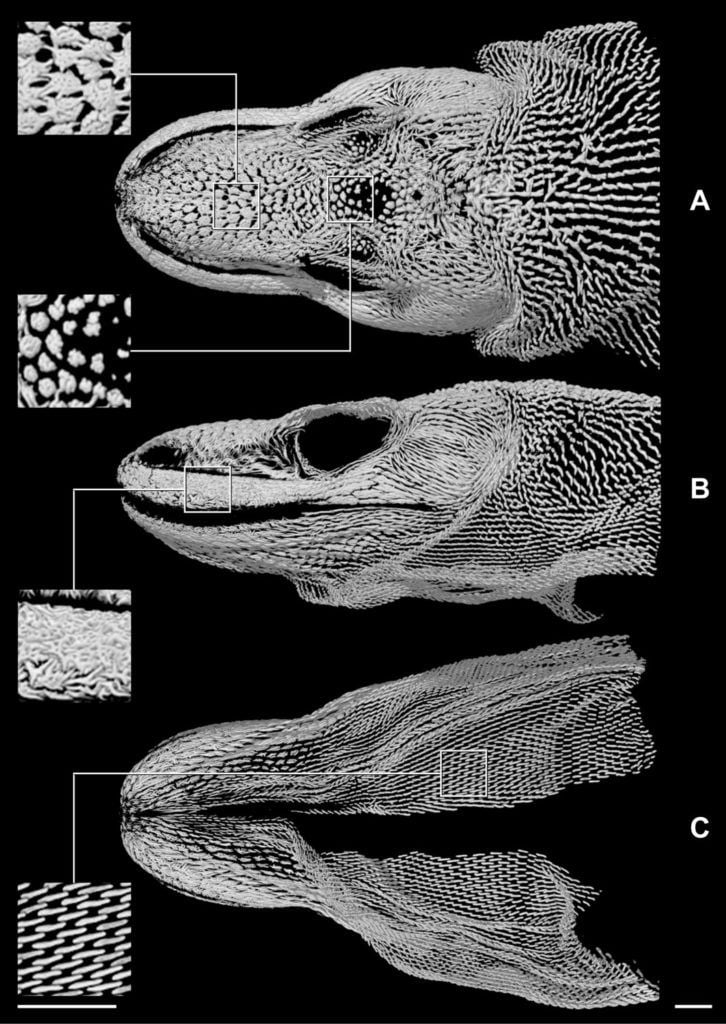

Researchers at the University of Texas at Austin decided to take a closer look. To start, the team took CT scans of two Komodo dragons, according to a press release. They obtained the the remains of a 9-foot-long, 19-year-old Komodo dragon that was donated to the Fort Worth Zoo after it passed away. (Only its head fit into the scanner.) The team also acquired a 2-day-old dragon that had died soon after birth.

They found that the adult dragons' osteoderms are truly next level. While other lizards with the bony armor only have patches of it made up of osteoderms of one or two shapes, the dragon had four distinct shapes of osteoderms that completely covered its head, except around their nostrils, eyes, and a light-sensing organ called the pineal eye on the top of its head. The study appears in the journal The Anatomical Record.

“We were really blown away when we saw it,” lead author Jessica Maisano, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Texas at Austin, says in the release. “Most monitor lizards just have these vermiform (worm-shaped) osteoderms, but this guy has four very distinct morphologies, which is very unusual across lizards.

The baby dragon, however, didn’t have any osteoderms, suggesting that the animals don’t need their armor until they're full grown. If the armor isn’t needed for protection from predators while the dragons are young, it suggests that the bone-mail is used to protect the dragons from one another when they reach sexual maturity. The animals are known to battle one another for mates or over food.

“Young komodo dragons spend quite a bit of time in trees, and when they’re large enough to come out of the trees, that’s when they start getting in arguments with members of their own species,” co-author Christopher Bell, also of the University of Texas at Austin, says. “That would be a time when extra armor would help.”

It’s possible that that not all Komodo armor is as hardcore as the study suggests. The adult that went into the CT scanner was one of the oldest captive dragons on record, and it's well-known that the animals add more and more layers of bone as they age. The team now wants to look at other Komodos of various ages to learn when they start to develop their osteoderms and how quickly their chain mail accumulates.

The dragons have other adaptations that keep them from permanently injuring one another as well. In July, researchers finished an eight year project to sequence the reptile’s genome. They found that the dragon has a unique set of genes that enhances its metabolism, which allows it to have more energy than other lizards during hunting and fighting. It also produces special blood-clotting proteins that protects it from the bite of other dragons, which have venom and blood-thinning agents in their saliva.

But currently, the dragons don’t need as much protection from one another as much as they do from humans. A ring of poachers that sold 41 Komodo dragons abroad was busted earlier this year. Hordes of tourists visiting Komodo National Park, the lizard’s stronghold, have also damaged the dragon’s habitat. That’s why Indonesia is considering closing the park to visitors in 2020 to let the dragons reproduce in peace and allow the trampled vegetation to re-grow—or perhaps to let the dragons add another layer to their already thick skin.