Landmark Exhibition Takes You Inside the Exuberant, Diverse World of the Fatimid Dynasty

Toronto’s Aga Khan Museum brings together 87 pieces from collections across the globe

Between the 10th and 11th century, the Fatimid dynasty ruled over a vast and formidable empire that stretched across swaths of North Africa and the Middle East. After the Fatimids conquered Egypt, they chose Cairo as their capital city, and built it into a thriving metropolis filled with sumptuous architecture and a diverse culture. But by the end of the 11th century, the dynasty had started to crumble.

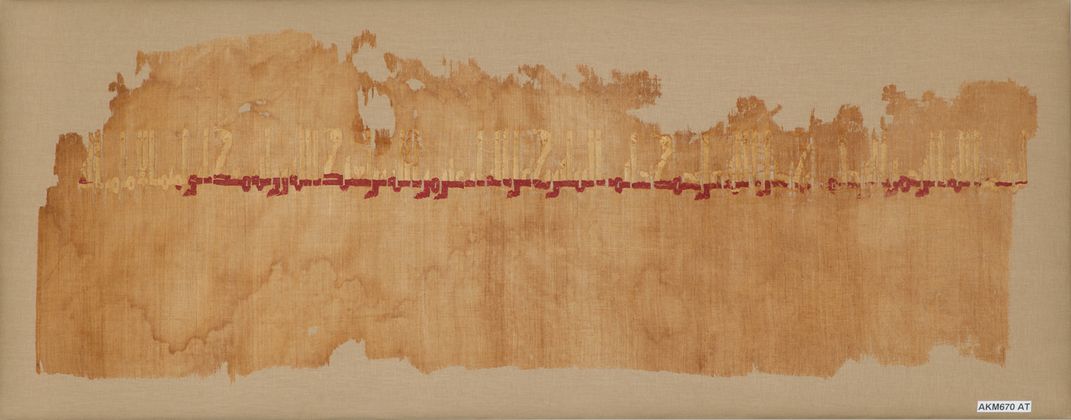

Political and economic turmoil left Fatimid caliphs unable to pay their soldiers, who responded by pillaging the royal palaces. After the great Islamic military leader Saladin finally brought an end to the dynasty in 1171, Fatimid art and architecture were deliberately destroyed. As a result of these cataclysmic events, very little of Fatimid material culture survives today—an unfortunate reality that makes a new exhibition on Fatimid art on view at Toronto’s Aga Khan Museum all the more remarkable.

The World of the Fatimids brings together 87 pieces from collections across the globe. Some, like a series of engraved marble panels from a Fatimid palace in Cairo, have never been publicly displayed before. The World of the Fatimids also marks the first major exhibition on the Fatimid dynasty to go on view in North America.

Hints of the Fatimids’ downfall lurk in various corners of the gallery. The aforementioned panels, for instance, are engraved with swirling foliage and large peacocks—one of which is starkly unfinished, possibly because construction on the palace was interrupted by the invasion of 1171. The dearth of surviving Fatimid objects presented a unique challenge for the curators of the exhibition.

“If you want to tell a story, you have to look very carefully which of these surviving objects to choose,” Ulrike Al-Khamis, director of collections and public programs, tells Smithsonian.com.

The narrative that unfolds through the artifacts on display reveals an opulent, sophisticated culture, with an influence that stretched all the way to Europe and the Near East. On view are elaborately engraved metal items, among them banquet trays, an oil lamp, and a gem box in the shape of a hare-like mythical creature, with a hole cut into its top so jewels could come tumbling out.

The Fatimids owned thousands of items made from rock crystal, some of which can be seen at the new exhibition. There is, for instance, a twinkling chess set made entirely from crystal, and a thick crystal crescent that was later taken to Europe and incorporated into the finial of a priest’s chair. Another highlight is a large ivory wine horn, its surface packed with engravings of animals.

“I love it so much,” Al-Khamis says of the artifact. “There are so many stories it tells us about early globalization, if you like, with the Fatimids being part of an enormously wide-reaching international network of trade routes into the very heart of sub-Saharan Africa, to bring things like ivory."

That it's unclear whether the horn itself originated in Cairo, Palermo or Southern Italy, she explains, speaks to that vigorous exchange of artifacts and ideas.

While the Fatimids were intimately connected to foreign cultures though trade, they set themselves apart with their figural art, which is detailed and expressive—humorous, even. At the Aga Khan exhibition, pottery fragments bear the faces of a heavily browed woman, her mouth set into a displeased squiggle, and a turban-clad man with his eyes rolling upward. An intact bowl, overlaid with a golden glaze, shows a valet attending to a cheetah; the animals were trained by the Fatimids to hunt gazelle. With his hands in close proximity to the cheetah’s gaping mouth, the valet looks mildly terrified.

The Fatimids’ proclivity for exuberant, winking figural art speaks to “a certain kind of intangible culture that lends itself to satire and to comedy,” Al-Khamis explains. She attributes the Fatimids’ distinct artistic style to the unique environment of the empire’s major cities, which were thrumming hubs of diversity.

The Fatimids adhered to the Ismaili branch of Shi’i Islam. While they notably clashed with Sunni Muslims of the Abbāsid dynasty, which was based in Baghdad, at home in Egypt, which boasted large populations of Jews and Coptic Christians, the Fatimids co-existed peacefully with other religions—a reality born out in the artifacts on view at the Aga Khan.

An 11th-century bowl, adorned with gold paint and covered with a shimmering glaze, shows a Coptic priest swinging an incense burner. The bowl is clearly a luxury item, suggesting that the Coptic clergy enjoyed elevated status in the Fatimid world. The exhibition also features an ornate wooden mihrab, or prayer niche, from the Cairo mausoleum of a Muslim holy woman. Nearby is a photograph of an arch from the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo, which is very similar in design. Craftsmen of the Fatimid era, it seems, were executing grandiose works of architecture for multiple religious denominations.

These relics from centuries past offer modern viewers “starting points to think about this issue of pluralism and … tolerance,” Al-Khamis says. “It would be wonderful if people realized that history can actually offer up a lot of interesting departure points to contemplate the present in which we live—and even into the future.”

Update, April 10, 2018: Due to an editing error, the curator of this exhibition was incorrectly referred to as "he." The piece has been updated.