Explore Dorothea Lange’s Iconic Photos With These Online Exhibitions

Digital hubs from the Oakland Museum of California and the Museum of Modern Art showcase the American photographer’s oeuvre

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3c/0d/3c0d7f7f-25c4-477d-9660-6ebfec95b50f/crossroads_general_store_north_carolina_1938.jpg)

In 1936, photographer Dorothea Lange made headlines with her stunning portrait of Florence Owens Thompson, a 32-year old pea picker in Nipomo, California. The image—known as Migrant Mother—brought national attention to the plight of migrant workers and eventually became one of the most recognizable symbols of the Great Depression.

Lange’s work documenting the economic downturn was just one chapter in her prolific, four-decade career. Now, two online exhibitions—a newly debuted digital archive from the Oakland Museum of California and a digitized retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City—enable users to explore the full range of Lange’s oeuvre, from her 1957 series on an Oakland public defender to her portraits of wartime shipyard workers and her later snapshots of Irish country life.

The Oakland Museum is home to Lange’s personal archive, which contains memorabilia, field notes, 40,000 negatives and 6,000 vintage prints, according to a statement. More than 600 of these items are on display in the digital archive, reports Matt Charnock for SFist.

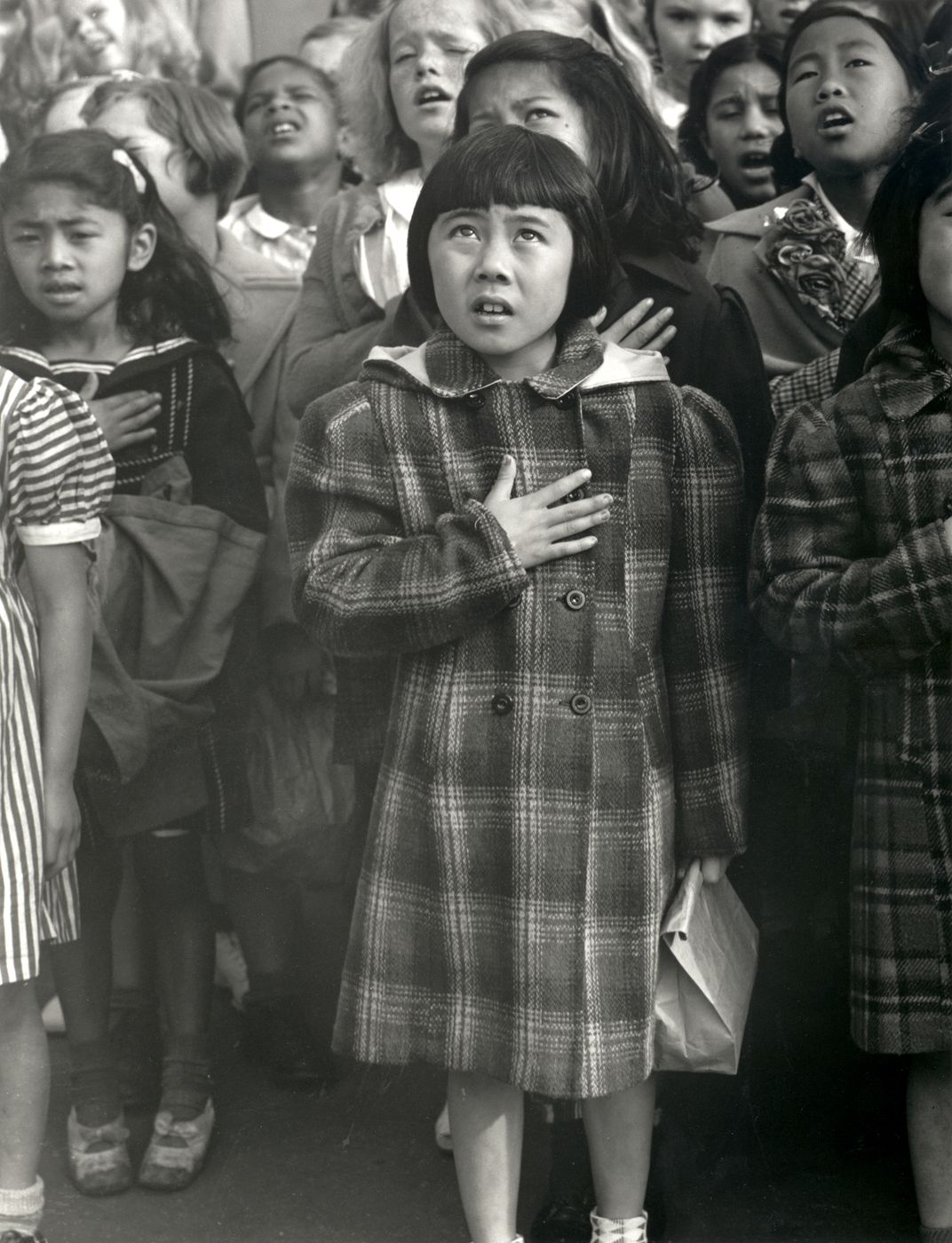

Tracing Lange’s work from the Great Depression through the 1960s, the archive explores the racist roots of poverty experienced by farm workers in the Jim Crow South and the harsh inequities faced by incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II. It also features artifacts from the photographer’s personal life, such as intimate portraits of husband Paul Schuster Taylor and their children.

Ephemera and personal photographs reveal Lange’s friendships with other great artists and photographers of her day, including Ansel Adams and Anne Brigman. In a handwritten letter from John Steinbeck dated to July 3, 1965—just three months before Lange’s death—the author thanks her for sending along a print, writing, “We have lived in the greatest of all periods.”

Steinbeck adds, “There have been great ones in my time and I have been privileged to know some of them and surely you are among the giants.”

The MoMA exhibition highlights Lange’s interest in the written word: As the the museum notes in a statement, the artist once commented that “[a]ll photographs—not only those that are so called ‘documentary’ … can be fortified by words.” For Lange, words added essential context to images, clarifying their message and strengthening their social impact.

Reviewing “Dorothea Lange: Words and Pictures” for the New York Times in February, Arthur Lubow noted that Lange was one of the first photographers to incorporate her subject’s own words into her captions. In American Exodus, a photo anthology she created with Taylor in 1938, the couple documented the American migration crisis by pairing photos next to direct quotes from the migrants themselves.

“At a moment of contemporary environmental, economic, and political crisis, it feels both timely and urgent to turn to artists like Lange, who documented migration, labor politics, and economic inequities—issues that remain largely unresolved today,” wrote curator River Bullock for the MoMA magazine in February. “Lange was needed in her time, but we may need her even more urgently now.”

Lange, for her part, understood that her work played a critical role in recording and remedying the social ills of her day.

“You see it’s evidence. It’s not pictorial illustration, it’s evidence,” she once told an interviewer. “It’s a record of human experience. It’s linked with history.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d1/c1/d1c16818-a03d-4208-b04f-a09521924b8e/screen_shot_2020-08-11_at_20828_pm.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)