Last Journalists Exit the Birthplace of Modern News

After 300 years, Fleet Street, the London thoroughfare home to dozens of newspapers and thousands of reporters, becomes a tourist stop

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/0e/f60e8264-3fba-4aef-9f95-02e8535bb6b7/1280px-londres_-_fleet_street.jpg)

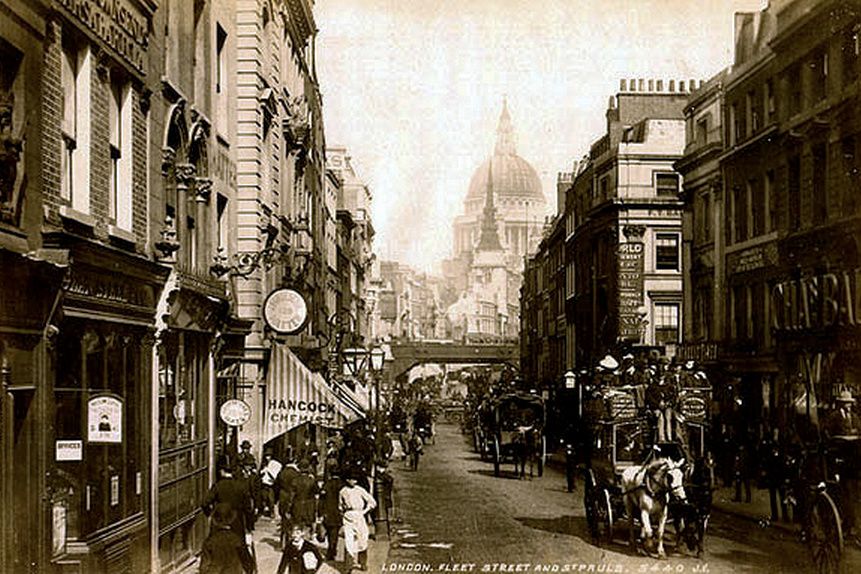

Anyone who picks up a morning paper, browses a news website or shakes their fist at cable news has one place to thank or blame: Fleet Street. The London thoroughfare has been the spiritual home of journalism since 1702 when the first London daily newspaper was printed there. By 1730, Matthew Green at The Telegraph reports the city had six daily papers, 12 tri-weeklies, and 13 weekly papers, most of them written and printed at offices on Fleet Street. But now, after three centuries, the last two ink-stained wretches left on Fleet Street have pulled up stakes.

Last Friday, reporters Gavin Sherriff and Darryl Smith of Dundee, Scotland’s Sunday Post were officially laid off. Their departures officially signaled the end of the run for journalism on the road linking Buckingham Palace to the City of London, reports Mario Cacciottolo at the BBC.

It’s a symbolic moment, but not news to those paying attention, as the street has been on a decline for several decades.

Journalists chose to colonize the street for several reasons, explains Green. It was already the home of book printing and book selling in London when the newspapers came to prominence, so it was a natural choice. As a main thoroughfare through the city, it was also a great place to find out the latest news from arriving travelers. A large number of pubs and mix of highbrow and lowbrow establishments meant it was a ideal for meeting sources, overhearing conversations and arguing about the day’s issues. European visitors to London in the 1700s were shocked by the inhabitants’ obsession with the news, with everyone from gentleman to illiterate workers either reading the paper or squeezing into pubs to hear someone read from the latest edition.

That obsession never died down. Papers chose to stay on Fleet Street and the surrounding area, and as journalism grew in sophistication, the papers built larger offices and printed their papers there. During World War II and the decades following, Fleet Street reached the peak of its prestige and influence. “At its height, Fleet Street was very, very important because television was in its early childhood, and there was no social media,” Robin Esser, who worked as a journalist on Fleet Street for 60 years, at one time serving as executive managing editor for The Daily Mail tells Cacciottolo. She estimates that 85 percent of information being made available to the public was delivered through the newspapers.

In the 1980s, many of the papers in the area were still using “hot metal” printing presses, which Jon Henley at The Guardian reports took up to 18 men to run. When media mogul Rupert Murdoch began buying up British papers, he wanted to get rid of the outdated equipment and replace it with more modern, less labor-intensive printing methods used in the U.S. and Australia. In 1986, Murdoch planned to uproot several of his newspapers and move them to a new, centralized complex in the area of Wapping. That precipitated a year-long event called the Wapping Dispute. Murdoch laid off 6,000 union printers, who picketed for almost a year before giving up. The move broke the back of the printer’s union and other newspapers based on Fleet Street soon began moving to more modern complexes in other parts of the city as well.

Today, Fleet Street is now full of sandwich shops, lawyers and banks, Conor Sullivan at The Financial Times reports. Most of the famous pubs, like the The Ye Old Cheshire Cheese and Punch tavern, once watering holes for hard-drinking journos, are now tourist traps or cater to the office lunch crowd.

It's the end of an era. DC Thomson, the company that owns the Sunday Post, will be keeping some advertising staff at the Fleet Street office, but with the editorial presence gone, the street is now simply just another stop on the London history tour.