Libraries Used to Chain Their Books to Shelves, With the Spines Hidden Away

Books have been around a long time, but the way we store them—stacked vertically, spines out—is a relatively recent invention

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2013090609002709_05_2013_strahov-monastery.jpg)

We’re going to go out on a limb and make you a bet: if you’ve got any bookshelves at all in your house, your books are standing up with the spines facing out, stacked together so they don’t tip over. But why are your books stacked this way? Well, the book title is printed on the spine. Fair enough. But, in the long history of storing books, shelving the way we do is a relatively modern invention.

For the Paris Review last year Francesca Mari dove into the surprisingly rich history of book storage, in which books have been tethered and piled every which way.

For the record, when you tuck a book away with the title-bearing spine pointing out, you’re carrying on a tradition that began roughly 480 years ago. “The first spine with printing dates from 1535, and it was then that books began to spin into the position we’re familiar with,” says Mari.

But before book, there were scrolls, and that’s where Mari’s story starts.

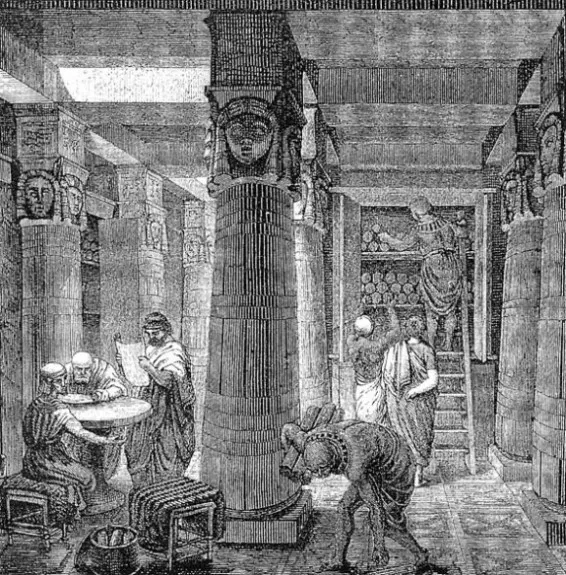

As it turns out, for a great deal of their history, shelves were much more haphazard than they are today. Before they even displayed books, they supported piles of scrolls. In the first century BC, Atticus loaned Cicero two assistants to build shelves and to tack titles onto his collection. “Your men have made my library gay with their carpentry work,” Cicero reported. “Nothing could look neater than those shelves.”

As scrolls gave way to books, new shelves and a new organizational system were in order.

For the next fourteen hundred or so years, books, as Henry Petroski, a professor of civic engineering and history at Duke, writes in The Book on the Bookshelf, were shelved every which way but straight up, spine out. Engravings of private studies show books piled horizontally, standing on the edge opposite their spine (their fore edge), as well as turned fore edge out.

Before the printing press books were ornate constructions, and in comparison to what came after they were both highly valuable and in short supply.

In the Middle Ages, when monasteries were the closest equivalent to a public library, monks kept works in their carrels. To increase circulation, these works were eventually chained to inclined desks, or lecterns, thus giving ownership of a work to a particular lectern rather than a particular monk.

When space got tight the monks moved their books to shelves, but they stacked them with the spines hidden. Which, as you can imagine, would have been quite confusing. The solution, Mari says: “Sometimes an identifying design was drawn across the thick of the pages.”

So, despite today’s prevailing norms, there’s no “right way” for shelving books. Rest assured, if you’re the kind of person who opts for the modern age’s second most popular method of organizing books—keeping towering stack near the bedside—your style of storage has roots stretching back to the dawn of books.

More from Smithsonian.com:

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/smartnews-colin-schultz-240.jpg)