The Library of Congress Has Digitized 155 Persian Texts Dating Back to the 13th Century

Offerings include a book of poetry featuring the epic Shahnameh and a biography of Shah Jahan, the emperor who built the Taj Mahal

:focal(396x354:397x355)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08/88/088828d7-5f7b-4bb7-bce8-7316faf3833b/image_1.jpg)

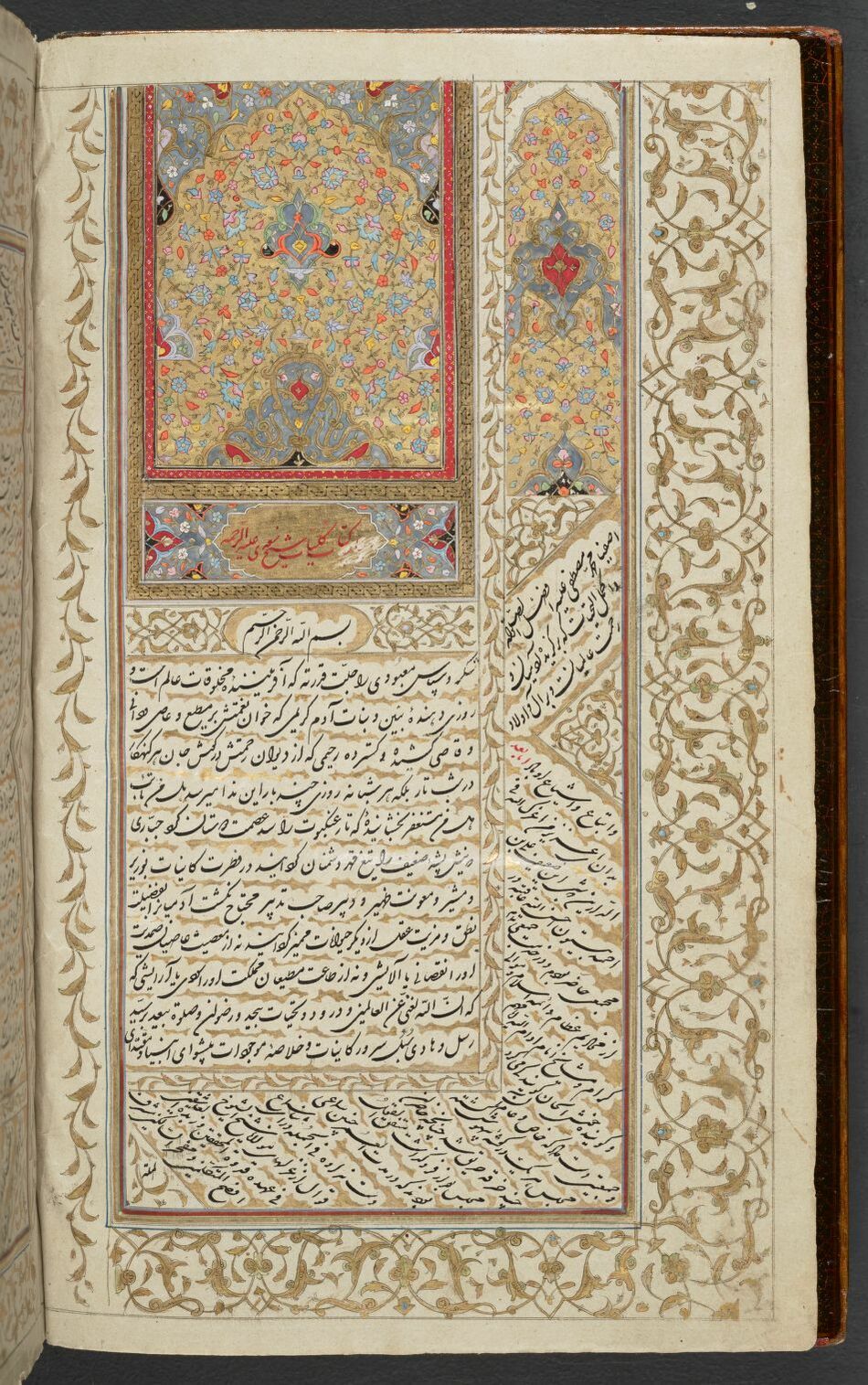

A sumptuously illustrated edition of classic Persian poetry by such luminaries as Saadi Shirazi and Jami, a 16th-century gold leaf map found in a volume chronicling the “wonders of creation,” and a 17th-century prayer book filled with colorful floral patterns are among the 155 Persian language texts now available via the Library of Congress’ online catalogue.

Spanning nearly 1,000 years and encompassing subjects as varied as literature, philosophy, religion, science and history, the newly digitized trove draws on documents from Persian-speaking countries including Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan, as well as places like India, Central Asia, the Caucasus and regions formerly controlled by the Ottoman Empire. The texts’ wide-ranging origins, in the words of reference specialist Hirad Dinavari, speak to the collection’s “diversity and cosmopolitan nature.”

“We nowadays are programmed to think Persia equates with Iran, but when you look at this it is a multiregional collection,” Dinavari expands in an interview with Atlas Obscura’s Jonathan Carey. “It’s not homogenous, many contributed to it. Some were Indian, some were Turkic, Central Asian. Various people of various ethnic groups contributed to this tradition.”

According to a press release, the digital catalogue includes a copy of the Shahnameh, an epic exploration of pre-Islamic Persia consisting of 62 stories divided into 990 chapters of 50,000 rhyming couplets, and a biography of Shah Jahan, the 17th-century Mughal emperor best known for building the Taj Mahal. Materials written in multiple languages, including Arabic and Turkish, are also present.

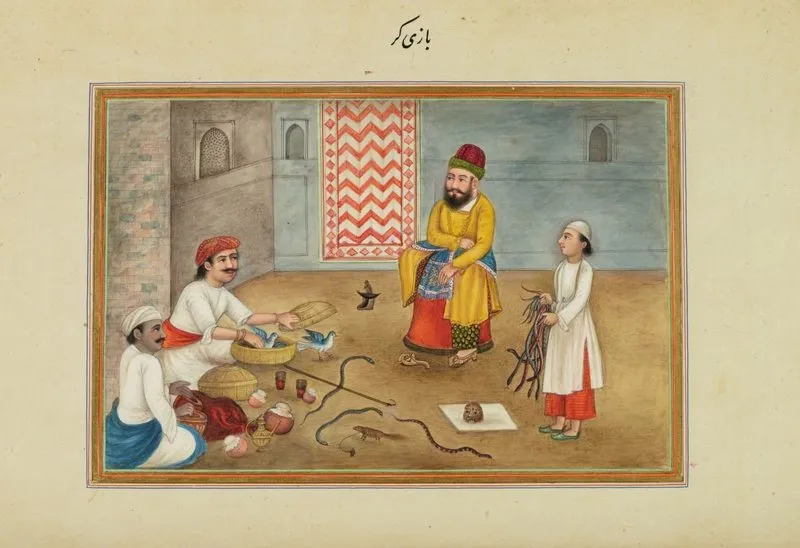

Another highlight is the History of the Origin and Distinguishing Marks of the Different Castes of India, an 1825 text penned by James Skinner, a Scottish-Indian lieutenant-colonel who served in the British military. The “voluminous treatise,” according to the Perso-Indica database, focuses on the Indian caste system, as influenced by profession and religious order, and is based on Sanskrit sources later translated into Persian.

Dinavari tells Carey that the book is a prime example of the “cultural fusion” fostered by Persian’s widespread use. (As a 2014 Library of Congress exhibition titled A Thousand Years of the Persian Book pointed out, Persian was once a lingua franca, or common cultural language, across a diverse swath of Asia and the Middle East.) Although the majority of Skinner’s work details the tribes, traditions and professions of Hindu India, it is still a Persian text—albeit one peppered with terms more commonly heard in the regional vernacular of India. The volume is even more unusual for its emphasis on everyday locals’ lives over the exploits of those at the top of society.

Much of the LOC’s rare Persian language collection stems from the efforts of Kirkor Minassian, an antiquities dealer and collector who specialized in Islamic and Near-Eastern artifacts and procured texts for the library during the 1930s. Since that time, the LOC has acquired a small number of additional manuscripts at auction, as well as through donations.

According to the library’s website, researchers from the Near East Section, spurred the popularity of a 2014 exhibition of more than 40 rare manuscripts and lithographic books, began digitizing the LOC’s Persian texts in 2015.

The collection’s digital debut was timed to coincide with Persian New Year, or Nowruz, which takes place during the vernal equinox and marks the dawning of a new chapter in life.

Manuscripts representing the majority of texts are currently available online. Assorted lithographs, early imprint books and Islamic book bindings are set to follow over the next several months.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)