Listen to a Lost Tape by a 23-Year-Old Lou Reed

A new album presents the earliest-known recordings of “Heroin,” “I’m Waiting for the Man” and “Pale Blue Eyes”

:focal(1771x1164:1772x1165)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/9d/ed/9dedfb90-2c80-46be-bb78-6cf8a1101d34/gettyimages-520816457.jpg)

On a shelf behind Lou Reed’s desk in his West Village office, Don Fleming and Jason Stern struck gold. Laurie Anderson, avant-garde artist and Reed’s widow, had enlisted the music producer and technical assistant to help her sort through the belongings of her late husband, following his death in 2013. Reed, a prolific songwriter who fronted the Velvet Underground and transformed New York’s experimental art scene, was a meticulous record-keeper, and he left behind a storage unit “stacked almost floor to ceiling” with unlabeled cardboard boxes, as Stern tells the Guardian’s Alexis Petridis, as well belongings scattered around his office.

What Fleming and Stern came across was a paper envelope, dated May 1965 and addressed by Reed to himself. Inside was a five-inch tape, containing demos that Reed recorded with his Velvet Underground co-founder, John Cale, including early versions of beloved songs like “Heroin,” “I'm Waiting for the Man” and “Pale Blue Eyes.” The package, notarized by a Harry Lichtiger, was presumably an effort by Reed to copyright his songs. (Research has revealed that Lichtiger was a “shonky local pharmacist, convicted of selling barbiturates without prescription,” per the Guardian.)

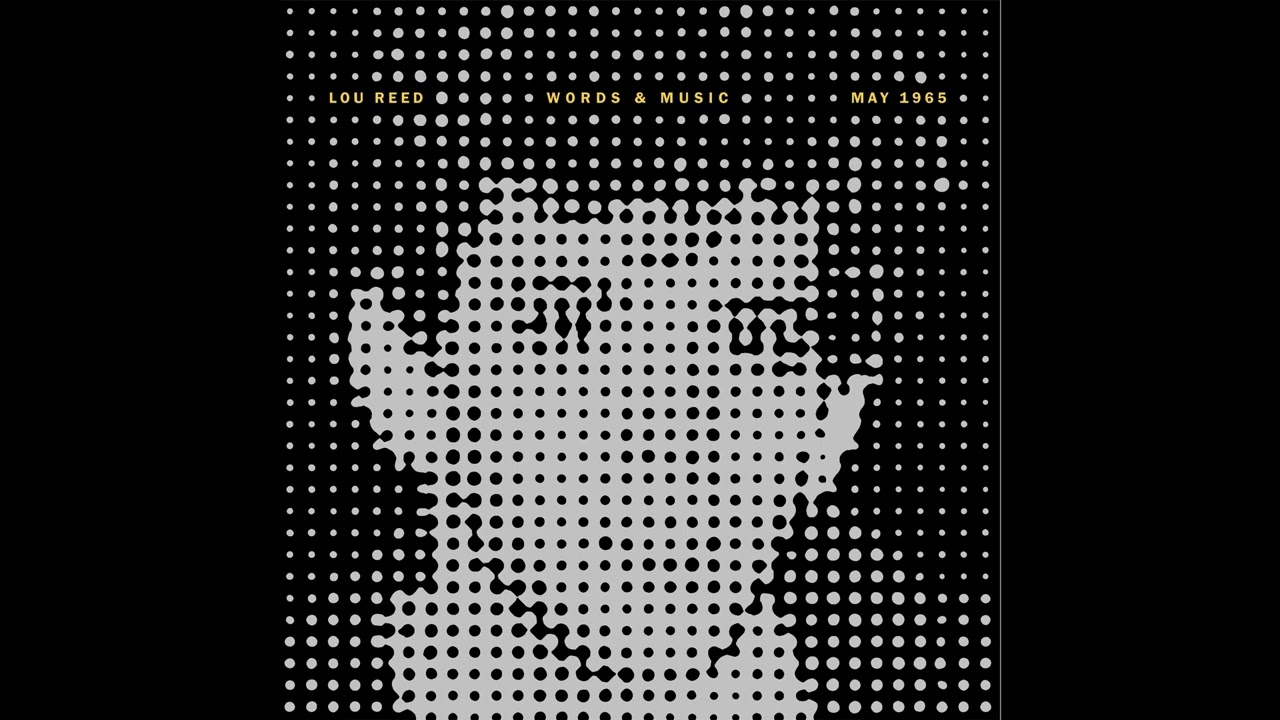

The demos, which include the earliest-known recordings of some of Reed’s most iconic songs, reveal a young man with a folk sensibility and an affinity for Bob Dylan, posing quite a contrast to the experimental rock and roll star Reed went on to become. This month, those precious demos, as well as a few recordings from other years, will be released as an album, Words & Music, May 1965, by record label Light in the Attic.

The album’s release is part of a larger effort led by Anderson to share what Reed left behind with the world, which also includes “Lou Reed: Caught Between the Twisted Stars,” a large-scale exhibition on Reed that draws from his archives. “Any kid starting a band, anyone, can now hear him searching around,” Anderson tells the Washington Post’s John Lingan.

In May 1965, Reed was newly 23 and a recent graduate of Syracuse University, where he majored in English. In his day job, he was a songwriter for pop label Pickwick Records. He’d recently teamed up with Cale, a Welsh classical prodigy who pushed the boundaries of music to strange, ambient places. Initially, Cale paid no mind to Reed, he told Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain for Please Kill Me, their 1996 history of punk.

“I first met Lou at a party and he played his songs with an acoustic guitar, so I really didn’t pay any attention because I couldn’t give a sh*t about folk music. I hated Joan Baez and Dylan—every song was a f***ing question,” Cale said. “But Lou kept shoving these lyrics in front of me. I read them, and they weren’t what Joan Baez and all those other people were singing.”

Somewhat surprisingly, the 1965 demos are delivered with a finger-picked guitar, a little harmonica and a Dylanesque drawl. As Petridis points out in the Guardian, “Cale sounds as if he’s having a high old time singing harmonies.”

When Anthony DeCurtis, author of Lou Reed: A Life, listened to the ’65 demos, the surprising style of music wasn’t the most striking—the skillful writing was. As DeCurtis tells the Washington Post, Reed was “mimicking so many kinds of songs. But on this, the lyrics are infinitely farther along than the music.”

The lyrics to “Heroin,” its demo shows, were effectively completed by 1965 (though the opening line was “I know just where I’m going”—the “don’t” appears to have been added later). The lyrics to other songs, on the other hand, changed drastically: “Pale Blue Eyes,” though musically similar to the released version, had almost entirely different lyrics in ’65 besides the chorus. “Men of Good Fortune” shares only a title with a song Reed later released during his solo career.

Musically and lyrically, Words & Music introduces Reed fans to a side of the artist they’ve never seen. But to Anderson, who was Reed’s partner for two decades before his passing, the young 20-something who recorded those demos sound intimately familiar.

The tape “sounds exactly like the Lou I knew,” Anderson tells the Washington Post. “It’s the ghost of a very ambitious young man who was working songs out. He’s laughing, he’s poking around. It’s the same person. You can hear someone taking chances.”