London’s Lucky Stone—Referenced by Shakespeare, Blake—Set to Return to Rightful Place

It’s been identified as a remnant of an ancient Roman monument, the altar employed in Druidic human sacrifice, even the stone that yielded Excalibur

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/8d/7f8dd07d-36d7-4460-9079-71b693657890/city_of_london_london_stone_-_geographorguk_-_493195.jpg)

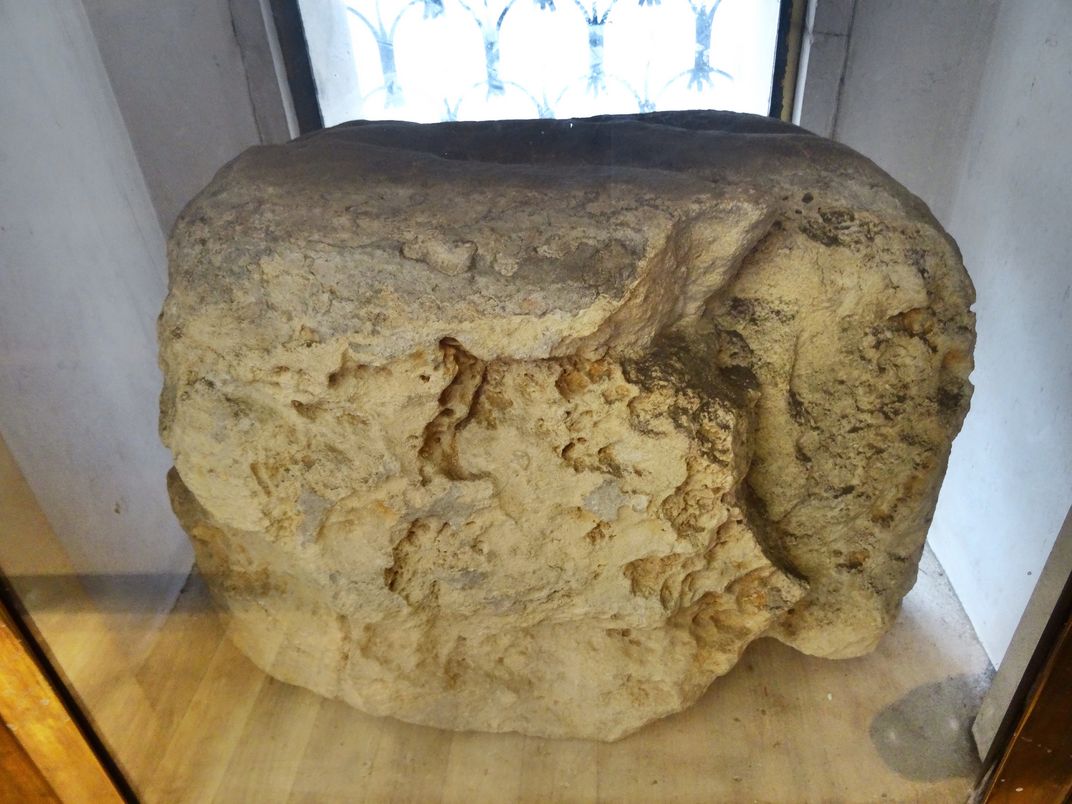

There are a host of theories surrounding the origins of the London Stone—an unassuming, nearly two-foot wide chunk of limestone that’s been linked for centuries with the changing fortunes of England’s capital city. Is it a remnant of a Roman monument? An ancient altar employed in Druidic human sacrifice? Or could it even be the stone that yielded King Arthur’s legendary Excalibur?

Despite all of the enigma surrounding it, the London Stone has lived a relatively quiet life in recent years; as the Guardian’s Charlotte Higgins reports, it has been nestled behind a protective iron grill on a Cannon Street building (which was, in various incarnations, a Bank of China office, a sporting goods store and, most recently, the stationery chain WHSmith) since 1962. In 2016, ongoing construction forced authorities to temporarily move the stone to the Museum of London, but as Mark Brown reports for a separate Guardian story, the historic block of limestone is now set to return to 111 Cannon Street on October 4.

According to a Museum of London blog post written by curator John Clark, the London Stone is entrenched in myth. Although the rock is alleged to have watched over London since prehistoric times, the type of oolitic limestone it’s composed of was first brought to the region during the Roman period. It’s possible the London Stone arrived in the city even later, perhaps during the Middle Ages or the height of the Saxon civilization.

By the mid-19th century, though, the London Stone had become irrevocably linked with Britain’s supposed founder, Brutus. Legend has it that Brutus was the leader of a group of Trojan colonists prior to the formation of the Roman Empire. There is no historical evidence for Brutus’ existence (most scholars attribute the tale’s invention to 12th-century writer Geoffrey of Monmouth), but the idea that Brutus brought the stone to the city took hold in popular imagination; an 1862 article written by Anglican priest Richard Williams Morgan further popularized the connection, giving rise to a “ancient” proverb: “So long as the Stone of Brutus is safe, so long will London flourish.”

In a 2009 paper, Clark notes that the earliest mention of the London Stone dates to between 1098 and 1108. The next significant reference pops up at the end of the 12th century, when the city’s first mayor is described as the son of Ailwin, resident of then-neighborhood “London Stone.”

The rock’s purported link with London’s welfare gained traction after 1450, when Kentish rebel Jack Cade struck his sword on the London Stone and deemed himself “Lord of London.” More than a century later, William Shakespeare dramatized the incident in Henry VI, writing, “Here, sitting upon London-stone, I charge and command that … henceforward it shall be treason for any that calls me other than Lord Mortimer.” The gravity of this threat is underscored by the play’s next lines, which find a soldier immediately struck down after addressing the newly minted lord by the wrong name.

Around the same time Shakespeare composed his account of the last Lancastrian ruler, John Dee, an occultist adviser to Elizabeth I, allegedly became obsessed with the stone. As Emily Becker writes for Mental Floss, Dee was convinced the rock wielded magical powers and even opted to live nearby it for a period of time.

Another William—the beloved British poet Blake—ascribed otherworldly significance to the London Stone during the early 19th century. In his 1810 work Jerusalem, Blake identified the rock as the site of Druid human sacrifice, writing, “And the Druids’ golden Knife / Rioted in human gore, in Offerings of Human Life / … They groan’d aloud on London Stone.”

Compared to the stone’s hazy (and largely unfounded) mythical origins, its longstanding presence on London’s Cannon Street is a historical fact. BBC News’ Sean Coughlan notes that the London Stone has survived “wars, plagues, fires and even 1960s planning,” largely remaining in a “setting not too far from where it [may have] stood when the Romans were building London.”

The last time the London Stone left Cannon Street was in 1960, when a similar bout of renovation prompted a temporary move to the Guildhall Museum. As Museum of London curator Roy Stephenson tells the Guardian’s Brown, it remains to be seen whether the rock’s upcoming restoration will have a positive influence on the city.

“We are hoping all the modern woes of life might be reversed,” Stephenson jokes, before tempering his comment with a nod to the London Stone’s storied past.

“You laugh,” he says, “but the last time it was restored, the Cuban missile crisis was sorted out.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)