Long-Forgotten Monument to Prison Reformer Will Be Reinstalled in New York Courthouse

Rebecca Salome Foster was known as the “Tombs Angel” in recognition of her work with inmates housed at a Manhattan prison known as “The Tombs”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/70/1d700241-cde2-4f14-8bc5-88c953aa21f8/rebecca-salome-foster-marble-pano_copy.jpg)

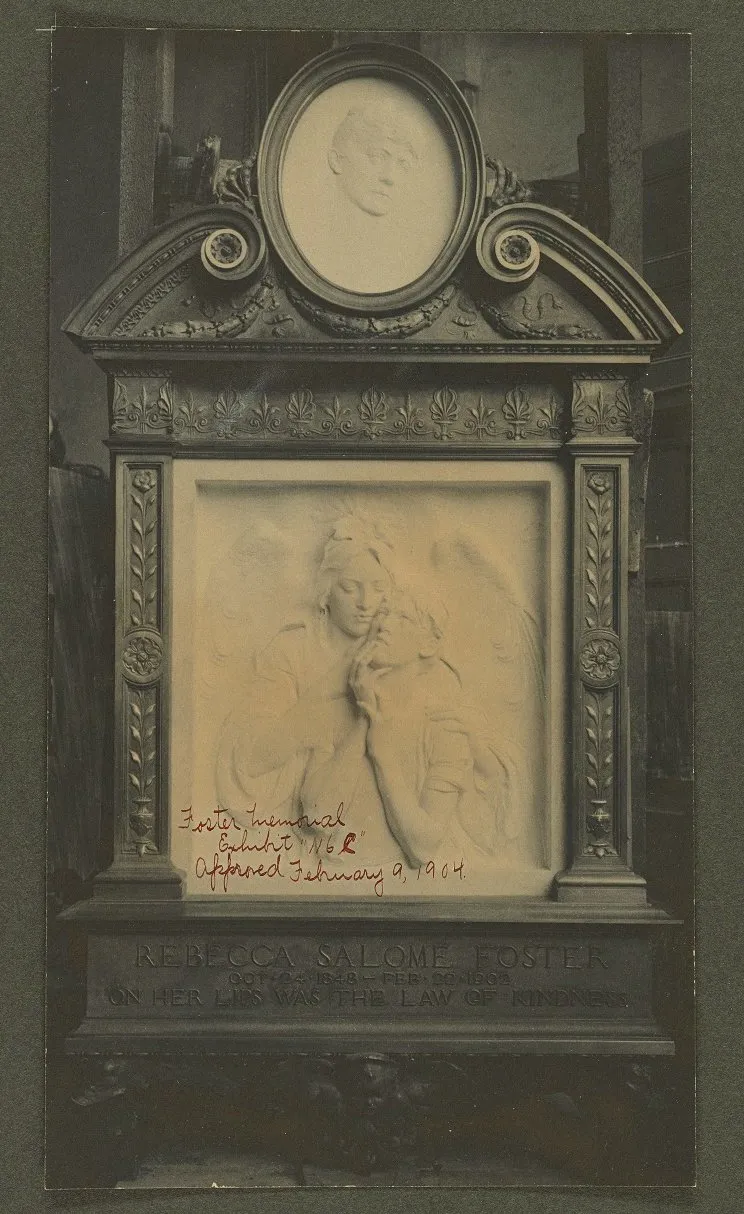

After Rebecca Salome Foster, a prison reform advocate dubbed the “Tombs Angel” in recognition of her work with inmates at a Manhattan detention center colloquially called “The Tombs,” died in a 1902 hotel fire, prominent judges and politicians—including then-President Theodore Roosevelt—lobbied for the creation of a memorial recognizing her contributions. Two years later, the resulting 700-pound monument was installed in the city’s old Criminal Courts building, where it remained until the space was torn down around 1940.

As Peter Libbey reports for The New York Times, the “Tombs Angel” monument languished in storage for nearly 80 years, occasionally appearing on officials’ radar but never returning to public view. Later this month, however, the central bas-relief section of the three-part memorial will resume its rightful place, standing newly refurbished in the lobby of the New York State Supreme Court.

The marble bas-relief, sculpted by Austrian-American artist Karl Bitter, once stood alongside a medallion likeness of Foster in a Renaissance-style bronze frame created by American architect and sculptor Charles Rollinson Lamb. Depicting an angel ministering to an individual in need, the scene is the only surviving element of the original 20th-century structure. According to Libbey, the frame and medallion both disappeared at some point during the monument’s long stretch in storage.

Foster’s philanthropic efforts began in 1886 or '87. As the widow of lawyer and Civil War General John A. Foster, she enjoyed a greater degree of influence with local judges and magistrates than a reformer without her connections would have had. Initially, Foster worked mainly with women and girls facing charges on petty offenses, but in the later years of her life, she dedicated herself almost exclusively to the Tombs, according to The New York Tombs: Inside and Out by author John Munro.

The Tombs, an overcrowded jail with severe structural issues affecting its sewage, drainage and water systems, was “a total hellhole,” in the words of Greg Young, co-host of New York City history podcast “The Bowery Boys.” The original building, dating to 1838, was replaced with a new City Prison the same year Foster died. This second iteration was, in turn, supplanted by a high-rise facility in 1941 and the still-surviving Manhattan Detention Complex in 1983, but the jail retains its macabre nickname to this day.

According to Herbert Mitgang’s biography of Samuel Seabury, a New York judge who collaborated with Foster on a number of cases, the reformer was dedicated to contributing “her services to protect and aid the unfortunate who found their way into the criminal courts.” Acting as a probation officer of sorts, she strove to help released inmates readjust to society, offering resources such as food, money, clothing and career advice. Working in tandem with Seabury, who served as chosen defendants’ counsel on a pro bono basis, Foster offered what Libbey describes as “a sympathetic ear, a zeal to investigate … cases, and a willingness to plead [the accused’s] cause with judges.”

Per a Los Angeles Herald article published shortly after Foster’s untimely death in February 1902, inmates and prison staff alike mourned the loss of their ardent supporter, reflecting on her “self-sacrifice and the place she had filled in the hearts of hundreds whom she had rescued.” In a letter endorsing the construction of a memorial to Foster, politician F. Norton Goddard echoed these sentiments, telling Judge William T. Jerome of those who admired “the thorough excellence of her work, and the great beauty of her character.”

John F. Werner, chief clerk and executive officer of the civil branch of the New York State Supreme Court, was instrumental in the 1904 monument’s restoration and reinstallation. As Libbey writes for The New York Times, Werner connected with Jeremy Ann Brown, a descendant of Foster who had previously inquired about the memorial’s status, and worked with the Municipal Art Society of New York, the New York Public Design Commission and the Department of Citywide Administrative Services to return the long-forgotten relief to its former glory.

“Timing is everything, and there’s all this interest now in the dearth of tributes to deserving women,” Werner says to Libbey, “and here we had one that dates back to 1904.”

The official rededication, scheduled for June 25, is sponsored by the Municipal Art Society’s Adopt-a-Monument program. To date, MAS notes on its website, the initiative has funded the conservation and maintenance of 53 works of public art found across all five of New York City’s boroughs.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)