You Can Now Explore the Louvre’s Entire Collection Online

A new digital database features 480,000 works from the Paris museum’s holdings

:focal(1053x663:1054x664)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/80/79/80798363-797c-438b-8a83-737594f2f09f/louvre_museum_228021559.jpeg)

When cultural institutions around the world were forced to shutter last year due to the Covid-19 pandemic, even the most popular art museum in the world felt the effects. The Louvre, home to such masterpieces as the Mona Lisa, welcomed just 2.7 million visitors in 2020—a 72 percent drop from 2019, when 9.6 million people flocked to the Paris museum.

But even as physical museums remained closed, art enthusiasts continued to seek inspiration in new ways: In that same pandemic year, 21 million people visited the Louvre’s website, according to a statement.

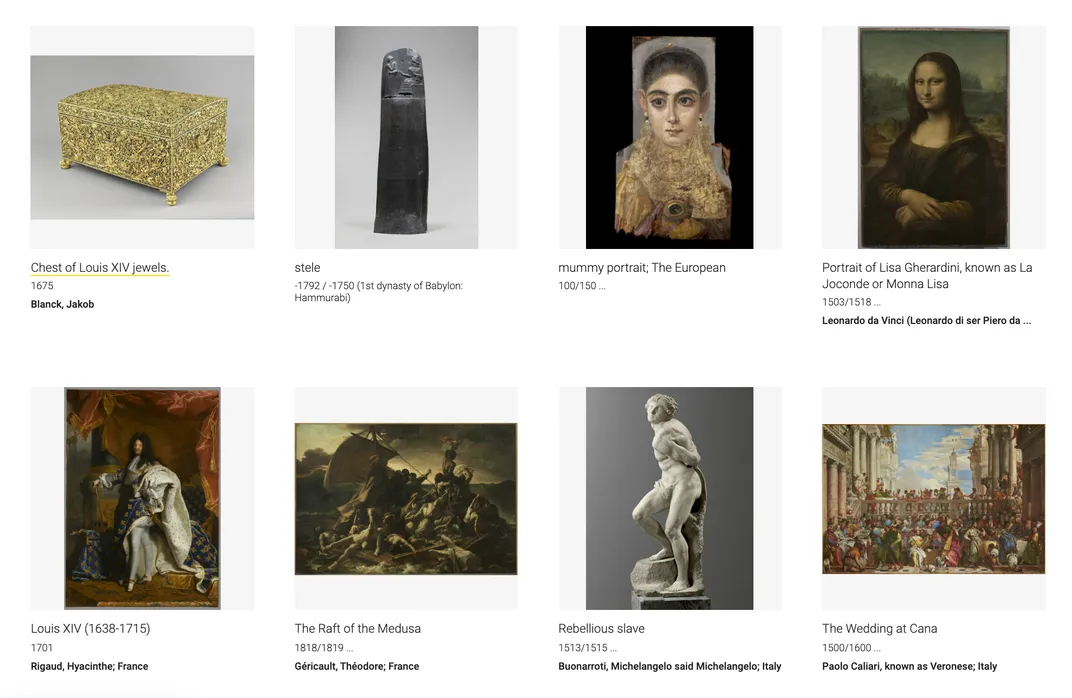

Thanks to a major website redesign and a new online collection database, browsing the historic museum’s holdings from home is easier than ever, reports Alaa Elassar for CNN. For the first time ever, the Louvre’s entire art collection is available to search online. The updated catalogue boasts more than 480,000 entries, from rare items stowed away in storage to the iconic Venus de Milo and Winged Victory of Samothrace. (Though the digital database is free to browse, offerings are not open access, meaning users cannot directly download, share or reuse the images.)

“Today, the Louvre is dusting off its treasures, even the least-known,” says the museum’s president, Jean-Luc Martinez, in the statement. “… [A]nyone can access the entire collection of works from a computer or smartphone for free, whether they are on display in the museum, on loan, even long-term, or in storage.”

Martinez adds, “The Louvre’s stunning cultural heritage is all now just a click away.”

Viewers can also click through an interactive map of the museum, virtually walking through the cavernous halls of the Renaissance castle or the sleek steel-and-glass pyramid designed by American architect I.M. Pei in 1989.

Previously, the public only had access to about 30,000 listings of works in the Louvre’s collections, reports Vincent Noce for the Art Newspaper. Per France24, more than three-quarters of the entries in the Louvre’s online collection contain images and label information. The museum plans to continue to expand and improve the database in the coming months.

The archive also includes the collections of the Musée National Eugène-Delacroix, which is run by the Louvre, and the nearby Tuileries Garden, as well as a number of Nazi-looted artworks that are in the process of being returned to their original owners’ families.

According to the new online catalogue, about 61,000 works stolen by the Nazis were retrieved from Germany and brought back to France after World War II. Of these works, 45,000 have been returned to their rightful owners. A number of others were sold by the French state. The remaining 2,143 unclaimed works were categorized as National Museum Recovery (MNR) and entrusted to French cultural institutions, including the Louvre, for safekeeping.

Despite the Louvre’s involvement in repatriation efforts, lingering concerns remain that Nazi-looted art may have made its way into the Louvre’s permanent collections during the war. Since hiring curator Emmanuelle Polack to lead a wartime provenance research project in January 2020, the Louvre has checked nearly two-thirds of the 13,943 works it acquired between 1933 and 1945, Martinez tells the Art Newspaper.

In the future, the museum plans to debut the findings of this research project on its website. The director notes that he has instructed curators to conduct a similar investigation of the thousands of artworks in the Louvre’s collections that hail from countries formerly under French control, such as Algeria, Tunisia, Syria and Lebanon.

The goal of this long-term project, he says, will be to identify which items in the Louvre’s encyclopedic collections were obtained through looting or colonial violence.

“Our collections are mostly archaeological and come from digs shared with the countries of origin,” Martinez tells the Art Newspaper, adding that the museum often obtained new archives through “bilateral” legal agreements.

At the same time, Martinez adds, “[M]useums like the Louvre served imperial ambitions and we have to deal with this history.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)