With Climate Change, Washington, D.C. Will Feel More Like Arkansas by 2080

Map predicts how climate change will feel in the city where you live by matching with a future climate twin

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5c/cc/5ccc5513-30b1-41b3-96b7-41b88524ed3a/cambio-climatico.jpg)

The threat of climate change is big, yet nebulous enough that it can be easy to ignore despite mounting evidence that humanity faces a future with more extreme heat waves, floods, drought and food shortages. Those hazards may just affect someone else. But a new study aims to make the effects personal by showing how the climate may change in your city.

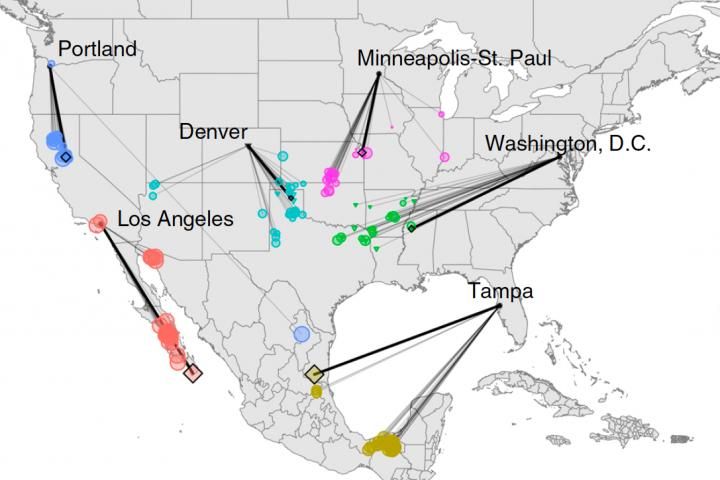

Philadelphia in 2080 will feel a bit more like the climate of current day Memphis, for instance. Researchers analyzed rainfall and temperature trends and compared them to climate models for 540 cities across the U.S. and Canada. Their results forecast a climate change "twin city" for the future of each urban area, writes Robinson Meyer for The Atlantic.

"Everything gets warmer," researcher Matt Fitzpatrick tells The Atlantic. Fitzpatrick is an associate professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. "I don't think I've seen a place that doesn't."

Wondering what the future may hold for a particular city? The researchers created a web tool that allows people to play around with locations and climate change scenarios and see for themselves. The cities analyzed are home to 75 percent of the population of the U.S. and 50 percent of the population of Canada.

Summers in Washington, D.C., for example, are already pretty hot and sticky—but just wait until the 2080s. Even with reduced carbon emissions, the nation's capitol is predicted to feel more like Paragould, Arkansas, where July temps regularly hover just above a sultry 90 degrees Fahrenheit, warmed by tropical air from the Gulf of Mexico. By comparison, Washington, D.C.'s July average high is just below 80 degrees. Say goodbye to the occasional snowpacolypse; Paragould currently gets an average of two inches of snowfall a year, according to U.S. Climate Data.

And keep in mind this is basically a best case scenario. If the world continues to put out unchecked emissions, D.C. residents could expect to experience weather currently seen by the people in Greenwood, Mississippi, where it's way hotter and more humid than Paragould.

Overall, cities in the northeast will tend to feel more like the subtropical climes found in the modern southeastern U.S., the researchers report in the journal Nature. Western cities should expect to feel more like the desert Southwest.

If the world doesn't cut back on emissions and climate change predictions hold true, the cities in the study will have conditions most similar to locations that are, on average, nearly 530 miles away from their modern day location.

One difficult finding is that many cities will experience change to a climate that doesn't look like anything currently in North America. "It really underscores this dramatic transformation of climate that occur over the next 60 years, in the lifetime of children alive today," Fitzpatrick tells Rachel Becker at The Verge.

The analogy isn't perfect, particularly where rainfall is concerned. The researchers had to pick the analogous city with the best fit to the predictions. Also, the results only offer a picture of the average climate. Cold snaps, heatwaves and more complicated phenomena—such as the effect of urban heat islands, where cities absorb more heat than surrounding areas—aren't part of this model, reports Matt Simon at Wired.

The point of the paper is to try and get people to think about how climate change may affect them. Fitzpatrick and his co-author Robert R. Dunn, an applied ecologist at North Carolina State University, write:

"Translating and communicating these abstract predictions in terms of present-day, local, and concrete personal experiences may help overcome some barriers to public recognition of the risks (and opportunities) of climate change."

The study could even spur action, suggests Kevin Burke, a climate scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who was not involved in the new study. “One notable outcome of this work is the potential for cities and their analog pairs to transfer knowledge and coordinate climate adaptation strategies," Burke tells Wired.

The changes mapped in the tool only account for the actual conditions people might experience when they step outside. The other effects of climate change remain to be seen. Maybe future tools could help people see how floods and heatwaves could come to their hometown. Or what new invasive species, weeds, pests or diseases may become their neighbors. What tools like this cannot do is predict the unexpected challenges a warming climate may force upon us.