This Map Shows the Scale of 16th- and 17th-Century Scottish Witch Hunts

The interactive tool tells the stories of 3,141 men and women accused of practicing witchcraft

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/42/9242da4e-0d60-4d56-9e8f-2df42038a5f0/screen_shot_2019-09-26_at_115013_am.png)

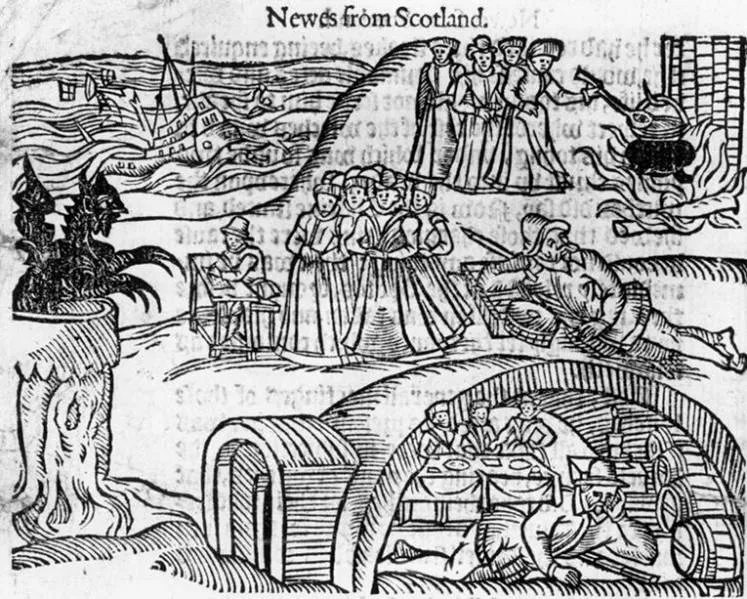

In 1629, an elderly Scottish woman named Isobel Young was strangled and burned at the stake on charges of witchcraft. As neighbors and relatives testified, Young—the wife of a tenant farmer based in a small village east of Edinburgh—was prone to “patterns of verbal and sometimes physical aggression,” as well as “odd magical characteristics.” Her husband, George Smith, added fuel to the fire claiming that his wife had attempted “to kill him with magic after quarreling about an unsavory house guest.” In total, court records show, 45 witnesses raised complaints against Young, “telling a story that unfolded over four decades.” The verdict was unanimous: guilty.

Young’s case is one of 3,141 recorded in a new interactive map created by researchers at the University of Edinburgh. Drawing on data collected for an earlier university project titled the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft, the tool visualizes an array of locations linked with Scotland’s 16th- and 17th-century witch hunts: among others, accused individuals’ places of residence; sites of detention, trial and execution; and spots targeted by infamous “witch-pricker” John Kincaid, who traveled the country in search of suspects bearing the "Devil’s mark."

“There is a very strong feeling out there that not enough has been done to inform people about the women who were accused of being witches in Scotland,” Ewan McAndrew, the University of Edinburgh’s Wikimedian in Residence, tells the Scotsman’s Alison Campsie. “… The idea of being able to plot these on a map really brings it home. These places are near everyone.

As Neil Drysdale of the Press and Journal reports, the map features an array of previously unpublished data, much of which was extracted from historical records by undergraduate Emma Carroll and uploaded to Wikidata, a public database created by the team behind Wikipedia. While some entries remain limited in scope, outlining little beyond the accused’s name and locality, others are replete with information.

Consider, for instance, the case of Janet Boyman, a healer who was charged with sorcery, witchcraft and consorting with fairies. Per the Survey of Scottish Witchcraft, Boyman, who was executed in 1572, predicted the death of the country’s regent, bore “five bairns” allegedly without feeling any pain and appealed to elvish spirits in hopes of curing a sick man. Today, historians consider Boyman’s trial one of the earliest and most comprehensive examples of witchcraft prosecution in Scotland.

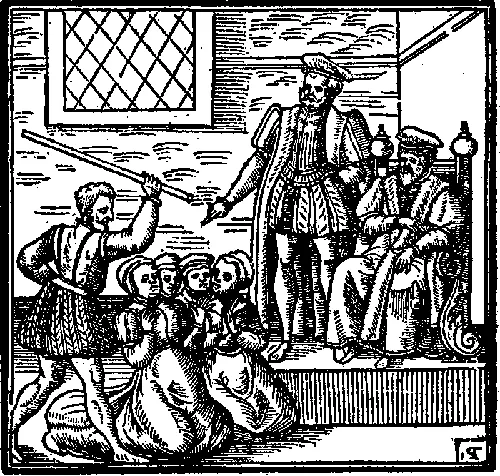

According to Edinburgh Live’s Hilary Mitchell, Scotland experienced four major witch hunts between roughly 1590 and 1727, when Janet Horne, the last Scot to be executed for witchcraft, was burned at the stake. Much of this ongoing mania can be attributed to the passage of a 1563 act that declared the practice of witchcraft a capital offense. James VI’s notorious witch-hunting fervor also contributed to the movement’s prevalence; in 1597, the king, soon to be crowned James I of England, published a treatise condemning witchcraft and encouraging vigorous prosecution of suspected practitioners.

As historian Steven Katz explains, Europe’s witch hunts stemmed from “the enduring grotesque fears [women] generate in respect of their putative abilities to control men and thereby coerce, for their own ends, male-dominated Christian society.” Ultimately that hysteria claimed as many as 4,000 lives in Scotland—double the execution rate seen in neighboring England, as Tracy Borman points out in History Extra. Although the majority of victims were women (per Mitchell, five times as many women were executed for witchcraft in Scotland than in England), men also faced trial and execution.

Speaking with the Scotsman’s Campsie, McAndrew says, “The map is a really effective way to connect where we are now to these stories of the past.”

He adds, “There does seem to be a growing movement that we need to be remembering these women, remembering what happened and understanding what happened.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)