How Halitosis Became a Medical Condition With a “Cure”

Bad breath wasn’t perceived as a medical condition until one company realized that it could help them sell mouthwash

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bc/c8/bcc87026-8820-4809-a9f0-8f12bca520a7/bad_breath_42-37440218.jpg)

Let’s get one thing straight right off the bat: no one is claiming that Listerine invented bad breath. Human mouths have stunk for millennia, and there are ancient breath freshening solutions to prove it. But, as Esther Inglis-Arkell writes at io9, in more modern days, advertisements for Listerine transformed halitosis from a bothersome personal imperfection into an embarrassing medical condition that urgently required treatment. Treatment that—conveniently—the company wanted to sell.

For decades after Listerine first hit the market in the 1880s, it was kind of a jack-of-all trades product. Originally invented as a surgical antiseptic (and named after the founding father of antiseptics, Dr. Joseph Lister), its uses were varied—they including foot cleaning, floor scrubbing and gonorrhea treating.

It was also marketed to dentists as a way to kill germs in the mouth, but no one paid much attention until the 1920s. That's when, as Inglis-Arkell writes, the owner of the company, Jordan Wheat Lambert, and his son, Gerard, came up with a marketing plan that would forever change the dental aisle. The key was an old Latin phrase that had long dropped out of general usage and which, according to writers over at Cracked, meant “unpleasant breath.”

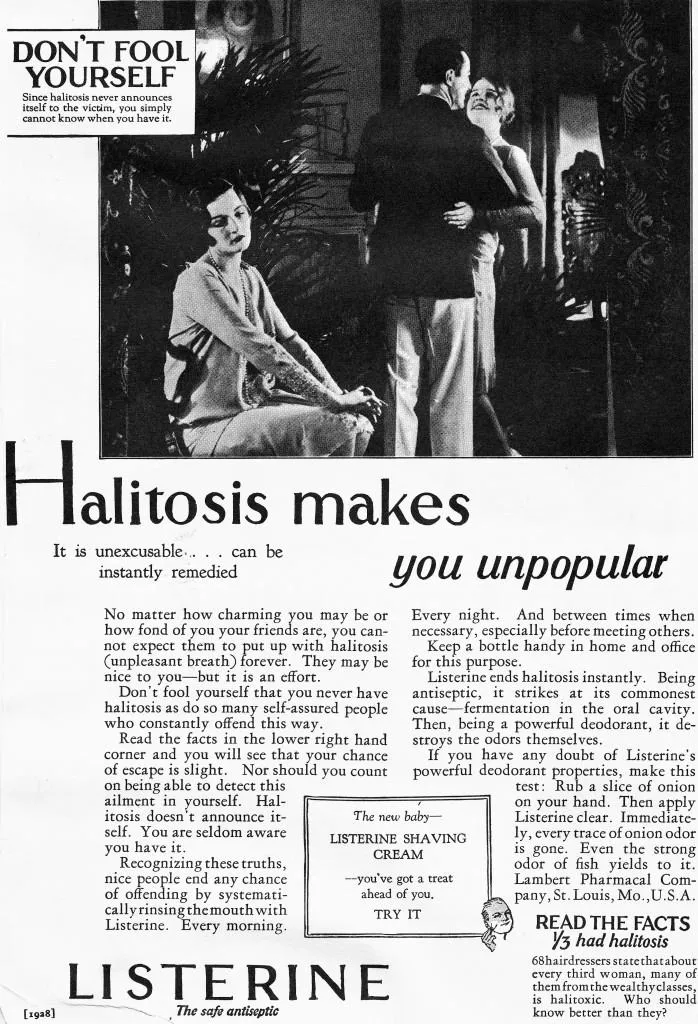

When the Lamberts started putting the vaguely medical sounding "halitosis" in their ads, they framed it as a health condition that was keeping people from being their very best selves. Inglis-Arkell describes the campaign’s direction:

A lot of companies were offering the emerging middle classes ways to cater to their social anxieties. Listerine ran advertisements in many papers talking about the sad, unmarried Edna, who remained single as she watched her friends getting married. It's not that she wasn't a great gal! It's just, she had this condition.

The marketing campaign was wildly successful. Even so, Lambert kept trying to sell the public on new uses for Listerine, making claims that it worked as toothpaste, deodorant and a cure for dandruff. But, with their no-longer-quite-so-stinky mouths, the people had spoken: Listerine was best as a mouthwash.

Ultimately, the bad-breath campaign was so successful that marketing historians refer to it as the “halitosis appeal”—shorthand for using fear to sell product. And, while the modern advertising industry is no stranger to creating a problem to sell its solution, Listerine’s medicalization of mouth odors might just be one of the most successful iterations yet.

But hey, at least there’s a little less bad breath in the world now than there was 100 years ago.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lauraclark.jpeg)