This Fancy Footwear Craze Created a ‘Plague of Bunions’ in Medieval England

Elite Europeans who wore pointed shoes toed the line between fashion and fall risk, a new study suggests

:focal(772x492:773x493)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/65/8e/658e3d18-e34c-476b-8d3f-db1a2331e373/screen_shot_2021-06-11_at_84704_am.png)

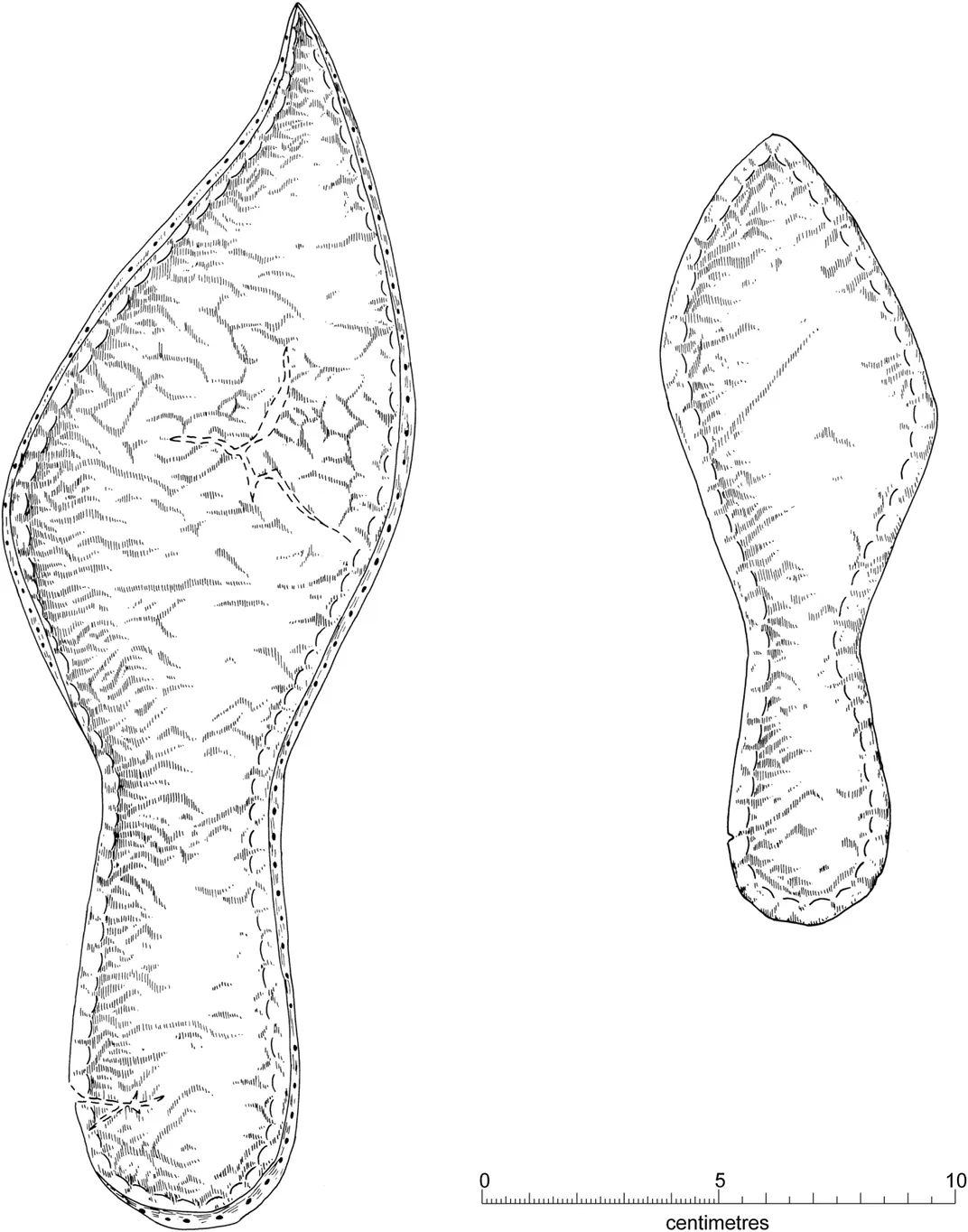

During the 14th century, a quirky fashion craze swept Europe’s wealthiest off their feet. Rejecting the functional, round-toed footwear of the past, lords and ladies donned crakows, or poulaines—shoes with extraordinarily long toes that tapered to an elegant point.

A new study from scholars in England and Scotland suggests that high society’s statement footwear toed the line between fashion and injury. Writing in the International Journal of Paleopathology, the team reports that the rise of elongated shoes in late medieval Cambridge led to a sharp increase in hallux valgus of the big toe, or bunions.

In other words, write study co-authors Jenna Dittmar and Piers Mitchell for the Conversation, “[i]t seems clear that the increasing pointiness of shoes unleashed a plague of bunions across medieval society.”

Hallux valgus is a small deformity that finds the big toe angled outward with a bony protrusion at its base—a development that makes walking painful. Some people have a genetic predisposition for the affliction, but most form bunions by wearing constrictive boots or shoes, according to a statement. (High heels are notorious in this regard.)

For the study, Dittmar, Mitchell and their colleagues analyzed 177 skeletons unearthed at burial sites in and around Cambridge. They found that just 6 percent of individuals buried between the 11th and 13th centuries bore evidence of bunions on their feet. Meanwhile, 27 percent of individuals buried in the 14th and 15th centuries suffered from bunions, some for their entire lives.

The skeletal remains exhibit “very clear osteological signs that the toes were pushed laterally,” Dittmar tells CNN’s Katie Hunt. “And there’s basically holes in the bone suggesting that the ligaments were pulling away.”

She adds, “[It’s] painful to look at the bone.”

Poulaine wearers also ran the risk of tripping over their own feet. Skeletons with evidence of hallux valgus were more likely to have fractures on their upper arms—likely the result of attempting to catch oneself after stumbling over complicated footgear, per the statement. Both the shoes and the accumulated bony bumps would have greatly affected medieval people’s balance, making them more prone to falls.

“We were most impressed by the fact that older medieval people with hallux valgus also had more fractures than those of the same age who had normal feet,” Mitchell adds in an email to Isaac Schultz of Gizmodo. “This matches up with modern studies on people today who have been noted to have more falls if they have hallux valgus.”

The poulaine trend may have first emerged in the fashionable royal courts of Krakow, Poland, around 1340, as Sabrina Imbler reported for Atlas Obscura in 2019. Shoemakers fashioned the footwear out of leather, velvet, silk, metal and other fine materials, stuffing them with moss, wool, hair or whalebone to make sure they didn’t lose their shape. (Speaking with Guardian’s Nicola Davis, Mitchell compares the historical shoes to the “ridiculously long, pointy shoes” seen in the 1980s British comedy show “Blackadder.”)

Most poulaine adherents were wealthy men who wore cumbersome shoes to advertise their leisure and emphasize their inability to partake in physical labor. The extravagant footwear was sometimes considered offensive or racy and, writes Andrew Millar of the Museum of London, was even associated with sodomy. Discourse surrounding poulaines reached such heights that in 1463, England’s Edward IV passed sumptuary laws in London that limited toe length to a mere two inches, per Atlas Obscura.

While few intact examples of the shoes survived to the present day, depictions of the sharp footwear abound in the pages of illuminated manuscripts. Scribes often depicted long-toed shoes as extending beyond the border of an image so as to visually emphasize their length, noted Ruth Hibbard in a 2015 blog post for the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Earlier this year, Dittmar and her colleagues published a separate survey of 314 individual skeletons unearthed in medieval burial sites around Cambridge. Writing in the Journal of Physical Anthropology, the researchers reported that social inequality was literally “recorded on the bones” of lower-class medieval workers, who suffered traumatic fractures, breaks and other injuries at a higher frequency than their wealthier neighbors.

In a similar vein, Dittmar and Mitchell’s more recent study found that the prevalence of bunions broke down along socioeconomic lines—but in the opposite direction. Just 3 percent of the people interred in the poorer, rural graveyard bore signs of bunions; comparatively, a staggering 43 percent of the wealthy individuals buried in an Augustinian friary were hobbled by the deformity.

Five of 11 clergy members bear the telltale marks of having worn tight-fitting shoes throughout their lives. This fits with what researchers know about clergy customs at the time, the researchers note. According to the statement, the church explicitly forbade clergy from wearing pointy shoes in 1215—but the trend proved so popular that the Magisterium was forced to issue similar decrees in 1281 and 1342.

As Mitchell adds in the statement, “The adoption of fashionable garments by the clergy was so common it spurred criticism in contemporary literature, as seen in Chaucer’s depiction of the monk in the Canterbury Tales.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)