Baseball’s Leading Lady Championed Civil Rights and Empowered Black Athletes

Effa Manley advocated for Black rights as a Negro Leagues team owner in the 1930s and ‘40s

:focal(1490x1005:1491x1006)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/a8/f2a87cfe-7126-428d-b4f7-0bd87219ae9c/gettyimages-73522258.jpg)

In 2006, Effa Manley, co-owner of the Negro Leagues’ Newark Eagles and an ardent civil rights activist, became the first—and, to date, only—woman inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

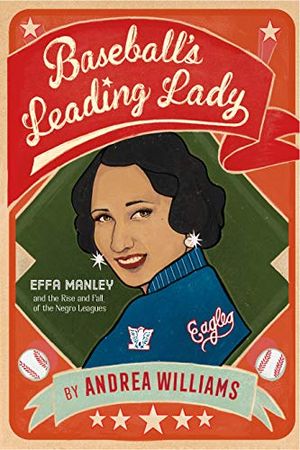

Forty years after Manley’s death in 1981, a new young adult book documents her extraordinary life, examining how she led her team to the Negro League World Series Championship in 1946. Author and journalist Andrea Williams decided to write Baseball’s Leading Lady: Effa Manley and the Rise and Fall of the Negro Leagues after working at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

“Seeing Effa and what she accomplished was really eye-opening,” Williams tells Alison Stewart of WNYC’s “All Of It.” “… There had been female owners before in the Major League Baseball and Negro Leagues. She didn’t just own the team, she did all of the day-to-day stuff, did all the player contracts and negotiations, ordered the equipment and managed the books. And she did it back then.”

Manley began her rise to the top of Negro League baseball after marrying her second husband, Abe, in 1935. The couple established the Newark Eagles the next year, with Manley taking charge of the operation. She was a natural at running the business, scheduling games, developing promotions and assisting players with their problems.

“This is the benefit of having a woman around, right?” Williams tells Evan F. Moore of the Chicago Sun-Times. “Men are one-track-minded, and [women are] thinking about all the things and not just the present ramifications. She really was about that life.”

Baseball's Leading Lady: Effa Manley and the Rise and Fall of the Negro Leagues

The powerful true story of Effa Manley, the first and only woman inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame

Per the Sun-Times, Manley was one of the reasons why baseball lovers today know the records of many Negro League players. She and other team owners insisted that African American newspapers publish statistics from each game; these records now represent a treasure trove for historians.

“We only know what we know about the Negro Leagues because of the work of Black papers and Black writers,” Williams tells the Sun-Times.

As Shakeia Taylor wrote for SB Nation last year, Manley’s race is “a source of quiet controversy”: She “lived as a Black woman, and was known as such by the Black community” for much for her life, but later said that she was actually a white woman. Manley’s mother, who may have been white or biracial, reportedly had an affair with a white man but only revealed her daughter’s true parentage when she was a teenager.

“Effa Manley had a keen awareness of the color line and of how to navigate it. Her slippages in and out of whiteness and Blackness were always strategic,” said Amira Rose Davis, a historian at Penn State University, to SB Nation. “… Ultimately it was the ambiguity that came to define Effa’s racial identity, more than anything else.”

In 1935, Manley walked the picket line as part of a “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaign against companies in New York City that refused to hire African American employees.

Speaking with WNYC, Williams describes an instance when Manley confronted a business owner about this racist practice:

She tells him, “Look, we care about Black girls the way you care about white girls. If you don’t hire them, they are going to become prostitutes.” That moment speaks to Effa and her personality, style and refusal to play by the rules. This is the 1930s. The fact that she is in the meeting is monumental. The fact that she speaks up and says something like that at the time completely shatters everything. That’s what got the owner to change his mind.

Manley also took on the white establishment of Major League Baseball when managers began signing players from the Negro Leagues, starting with Jackie Robinson in 1947. While she supported the integration of baseball, Manley believed that white teams should pay for signing the stars that Negro League owners had invested so much time and effort in developing.

In a blog post for the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Isabelle Minasian discusses the numerous letters Manley sent to team owners, as well as Commissioner of Baseball Happy Chandler, protesting the raids on Negro League rosters. Her efforts paid off when Bill Veeck, owner of the Cleveland Indians, purchased the contract for Larry Doby, the first Black athlete to play in the American League, from her very own Newark Eagles in 1948.

“Manley’s continued advocacy paved the way for fair compensation for Negro League teams, and these letters in the museum’s collection demonstrate the strength and tenacity of the first woman to be inducted into the Hall of Fame,” Minasian writes.

As Williams tells the Sun-Times, she hopes that the book helps younger readers understand the historical context behind ongoing systemic injustice.

“How do we get the next generation on board so that we don’t have to have these issues? That’s the goal of writing this book,” she says. “And if I’m going to help the next generation, I have to write a book for kids that really tells the truth about our past and how the past has created our present. I wanted to tell the whole truth.”

Manley died in 1981 at the age of 84.

Fittingly, her tombstone reads, “She Loved Baseball.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)