Meet Four Japanese American Men Who Fought Back Against Racism During WWII

“Facing the Mountain,” a new book by author Daniel James Brown, details the lives of four 20th-century heroes

:focal(1411x931:1412x932)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/58/bf58d39e-9e80-44c6-a3b9-973cc1900814/43_review.jpg)

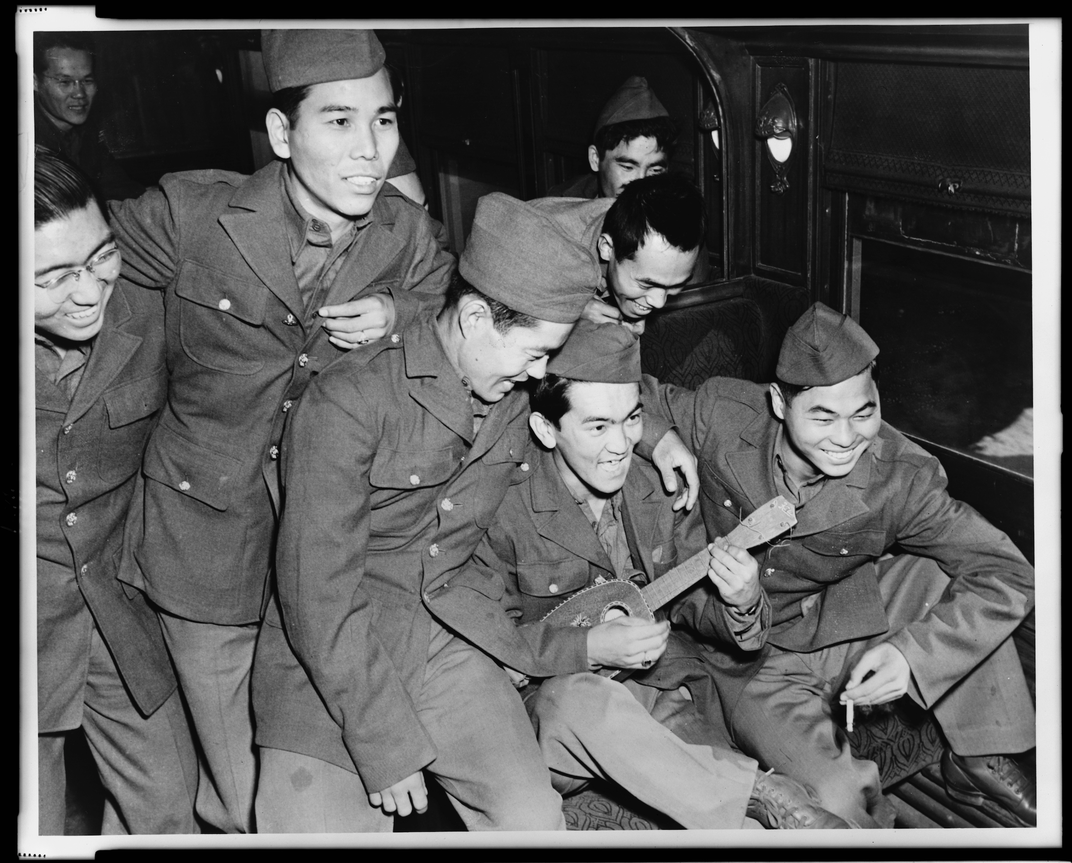

During World War II, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was the most decorated unit of its size in the United States Army. Comprised almost entirely of Japanese Americans, the regiment fiercely fought fascism across Europe while enduring racist rhetoric at home.

A new book by writer Daniel James Brown examines the courage and determination of four Nisei, or American-born children of Japanese immigrants, including three who fought in the 442nd. Brown is the bestselling author of Boys in the Boat, a narrative history of nine working-class Americans who rowed their way to the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II chronicles the lives of soldiers Rudy Tokiwa, Fred Shiosaki and Kats Miho, who distinguished themselves under fire in Italy, France and Germany, and conscientious objector Gordon Hirabayashi, who was imprisoned for protesting U.S. policies that saw some 120,000 Japanese Americans incarcerated in internment camps.

Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II

A gripping saga of patriotism, highlighting the contributions and sacrifices that Japanese immigrants and their U.S.-born children made for the sake of the nation

Published this month, the book arrives at a time of heightened violence against Asian Americans. The racism its subjects faced nearly eight decades ago often parallels the prejudice witnessed today. As Brown tells Mary Ann Gwinn of the Seattle Times, anti-Asian racism in the U.S. “started with the gold rush—Chinese workers being beaten, cabins burned down, lynching, the concept of a ‘yellow peril.’ It was really a general anti-Asian feeling.”

He adds, “By the 20th century it was more directed at Japanese immigrants, who were portrayed with images of rats and snakes and cockroaches. When Pearl Harbor happened, those images got pulled out and recycled, and during the Trump administration, some of those images were recycled again, associating Asians with illness and disease and plague.”

Born in California, Tokiwa was 16 when Japanese airplanes bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941. His family was forced to leave its farm and was eventually sent to an internment camp in Arizona. After he turned 18, Tokiwa answered the government’s provocative “loyalty questionnaire,” which sought to determine his allegiance, and joined the U.S. Army. He was assigned to the 442nd and shipped out for Europe.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/7a/8a7a31b0-4314-40fa-8ce6-e044d9a4cea8/screen_shot_2021-05-12_at_123904_pm.png)

Tokiwa saw combat in Italy, France and Germany, once single-handedly capturing four German officers while out on patrol, according to the Densho Encyclopedia. He also took part in the rescue of the so-called Lost Battalion (the 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry Regiment), whose men found themselves surrounded by German troops in France’s Vosges Mountains in October 1944. Per the Go For Broke National Education Center, the 442nd suffered hundreds of casualties as it fought for six consecutive days to reach the trapped unit. Tokiwa received the Bronze Star for his actions.

Shiosaki’s family, meanwhile, lived in a military district that did not force Japanese Americans into internment camps. Born in Spokane, Washington, he joined the U.S. Army when he turned 18 in 1943 and trained as a rifleman in Company K of the 442nd.

Like Tokiwa, Shiosaki took part in the rescue of the Lost Battalion. During the attack, he was struck in the stomach by shrapnel but was not seriously wounded. By the end of the rescue, he was one of 17 men in his company of 180 who was still able to fight. Shiosaki also earned the Bronze Star, as well as the Purple Heart.

Miho was enrolled at the University of Hawaii when Pearl Harbor was attacked. He could see the explosions from the campus and stood guard as a member of the school’s ROTC program. As Facing the Mountain notes, Miho joined the Hawaii Territorial Guard but was later dismissed because of his Japanese ancestry. His father was arrested and sent to an internment camp on the mainland U.S.

In 1943, Miho enlisted in the U.S. Army and was assigned to an artillery unit in the 442nd. While supporting the 3rd Army in Germany, his battalion traveled 600 miles and fired 15,000 rounds over just 55 days. Miho suffered permanent hearing loss as a result of repeated cannon firing.

For these men and others like them, serving their country during its time of need was a point of pride.

Speaking with the Seattle Times, Brown says, “[I]t honestly was Japanese tradition to various degrees. Many of them were also essentially American, so it was a compounded sense of motivation. They were convinced that it was better to die on a battlefield in Italy or France than to come back having shamed the family.” (As Damian Flanagan explained for the Japan Times in 2016, Japanese Bushido code condemned surrender to the enemy and instructed adherents “to fight to the very last man and woman.”)

Though not involved in active combat, Hirabayashi’s wartime odyssey was just as arduous as the other three’s. He was born in Seattle to Christian parents from Japan and later became a Quaker. Before Pearl Harbor, Hirabayashi registered for the draft but declared himself a conscientious objector due to his religious beliefs.

When the U.S. entered World War II, Hirabayashi believed that his citizenship would protect him. He protested Executive Order 9066, which enabled the U.S. government to forcibly relocate people of Japanese ancestry to the West Coast, and was arrested by the FBI for his defiance. Hirabayashi had to hitchhike to Arizona to begin his sentence and convince prison officials to accept him, as they had not yet received his paperwork.

“The dilemma that draft-age Japanese American men had, they reacted to it in different ways,” Brown tells the Seattle Times. “There were many, many resisters in the camps, but Gordon Hirabayashi was so careful in his reasoning. He made the perfect person to represent that point of view. He carefully laid out the principles as to why this should not be happening.”

Lawyers fought the conviction all the way to the Supreme Court, which upheld the sentence in Hirabayashi v. United States. In 1987, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reopened and reviewed the case, vacating Hirabayashi’s conviction with a writ of coram nobis, which allows a court to overturn a ruling made in error.

All four men are gone now—Shiosaki was the last survivor, dying last month at age 96—but they all lived to witness the U.S. government making amends. The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 addressed the “fundamental injustice” of what happened during the war and provided compensation for losses sustained by incarcerated Japanese Americans.

“The sacrifices of our parents and the sacrifices of the men in the 442nd were our way of earning that freedom,” Shisoki told Spokane’s KXLY 4 News in 2006. “The right to be called an American, not a hyphenated American and I guess that’s my message to everybody; that you don’t—this stuff doesn’t get given to you, you earn it. Every generation earns it in some way or another.”

At a difficult time in the country’s history, each of the four men followed the path that he believed was right. In the end, their faith in their country was rewarded with the acknowledgement that their rights had been violated.

As Brown writes in Facing the Mountain:

[I]n the end it’s not a story of victims. Rather, it’s a story of victors, of people striving, resisting, rising up, standing on principle, laying down their lives, enduring, and prevailing. It celebrates some young Americans who decided they had no choice but do what their sense of honor told them was right, to cultivate their best selves, to embrace the demands of conscience, to leave their homes and families and sally forth into the fray, to confront and conquer the mountain of troubles that lay suddenly in their paths.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/dave.png)