At the Met, Two New Monumental Paintings Foreground the Indigenous Experience

Cree artist Kent Monkman borrows from European artists while reframing problematic narratives about indigenous people

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4b/db/4bdb25ea-298c-4a46-86e0-8c47863cc554/gettyimages-630616112.jpg)

Starting tomorrow, visitors entering the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Great Hall will be greeted by two monumental paintings. These artworks echo the style of Europe’s Old Masters, but quite unlike paintings of centuries past, the new pieces depict the gender-fluid, time-traveling alter ego of an indigenous artist.

As Adina Bresge reports for the Canadian Press, the Met is set to unveil two dynamic new commissions by Toronto-based Cree artist Kent Monkman. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, a second persona who features prominently in Monkman’s body of work, appears on both sprawling canvases. Her inclusion is just one of the ways Monkman reimagines colonial-era paintings and foregrounds the indigenous experience.

Monkman’s commissions are the first in a series that invites contemporary artists to create new works inspired by pieces in the Met’s collection, according to the CBC’s Jessica Wong. Although Monkman is trained as an abstract artist, he was reportedly drawn to the representational style seen in the paintings that adorn the Met’s walls.

“There are many incredible things in the vaults, but I really wanted viewers to connect with some of the ‘greatest hits’ here at the Met,” the artist, as quoted by Wong, told reporters during a preview event. “I love the Old Masters. I love [Peter Paul] Rubens. I love Titian. I love Delacroix. ... These were striking images to me because it’s about this tension, these relationships, the dynamism of their poses.”

The resulting installation, titled mistikosiwak (Wooden Boat People), borrows from the European masters while simultaneously subverting them.

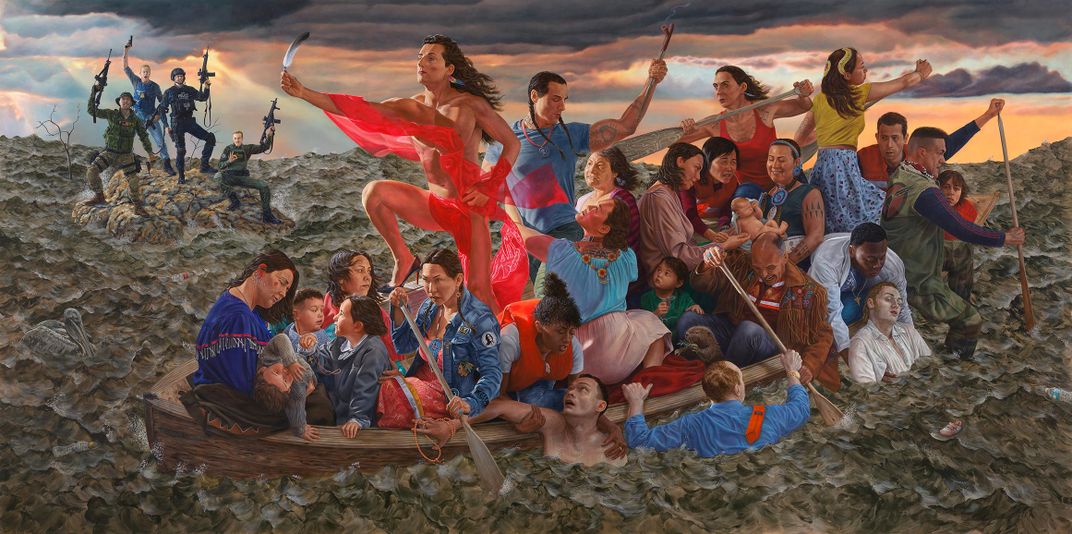

One painting, Resurgence of the People, was inspired by Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware, an 1851 commemoration of the general’s surprise attack on the Hessians during the Revolutionary War. In Leutze’s painting, colonial soldiers on their way to the attack are crammed into a boat; in Monkman’s interpretation, the boat is piloted by indigenous people. Miss Chief, resplendent in a red sash, leads the way. Some of the figures in the boat grasp people afloat in the sea. Standing on a rock behind them are men in combat gear, their guns raised to the sky.

“The themes are of displacement and migration: Indigenous people are being displaced again, and they’re setting sail,” Monkman tells Jarrett Earnest of Vulture. “But it also refers to other populations around the world that are being displaced now, not just for political reasons but because of the shifting climate as well.”

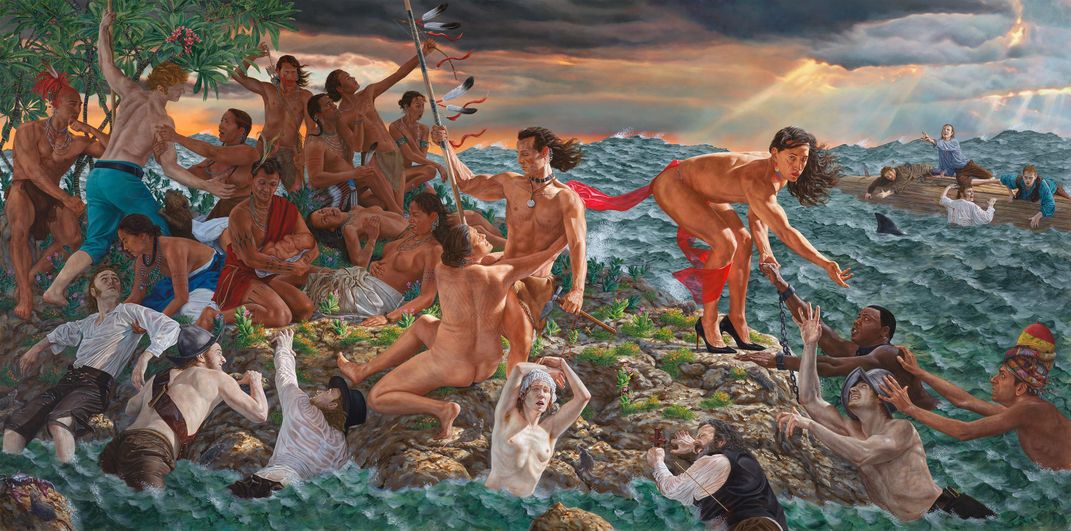

The second work, Welcoming the Newcomers, features Miss Chief and other indigenous figures pulling settlers from the sea onto the shores of North America. Monkman incorporated a number of influences into this painting, among them The Natchez by Eugène Delacroix. This 19th-century work is based on the popular Romantic novel Atala, which chronicles the fate of the Natchez people following attacks by the French in the 1730s. Delacroix’s scene shows an indigenous mother, father and newborn on the shores of the Mississippi River.

“In the story, the newborn baby dies shortly after birth because his mother’s milk is tainted by the grief of losing her people,” Monkman explains to Earnest. “The perception that indigenous people were dying out was mistaken, as the Natchez people and their culture continue to survive today. I use the image of a young indigenous family, echoed in both paintings (in the second as a same-sex couple), to emphasize indigenous resilience and survival.”

Mistikosiwak represents the Met’s latest attempt to bolster and diversify the representation of minorities within its hallowed halls. Earlier this year, for instance, the museum announced that it was hiring its first full-time curator of Native American art—a move that came not long after the Met launched an exhibition of Native American art in its American Wing, thus situating indigenous works within the broader narrative of the country’s art history.

“The Met is really taking a look at itself about art history, the kinds of stories we need to be telling,” Randy Griffey, a Met curator of modern and contemporary art, said during the press event, according to Wong.

With mistikosiwak, Monkman hopes to reframe problematic narratives about indigenous people while cementing their place within one of the world’s foremost art institutions.

“You want an audience to feel that we are very much alive and well,” he tells Bresge of the Canadian Press. “That's the message I like to carry with my work is that it’s about honoring indigenous people for our incredible resilience through some very dark chapters of history.”