Hidden Microbes and Fungi Found on the Surface of Leonardo da Vinci Drawings

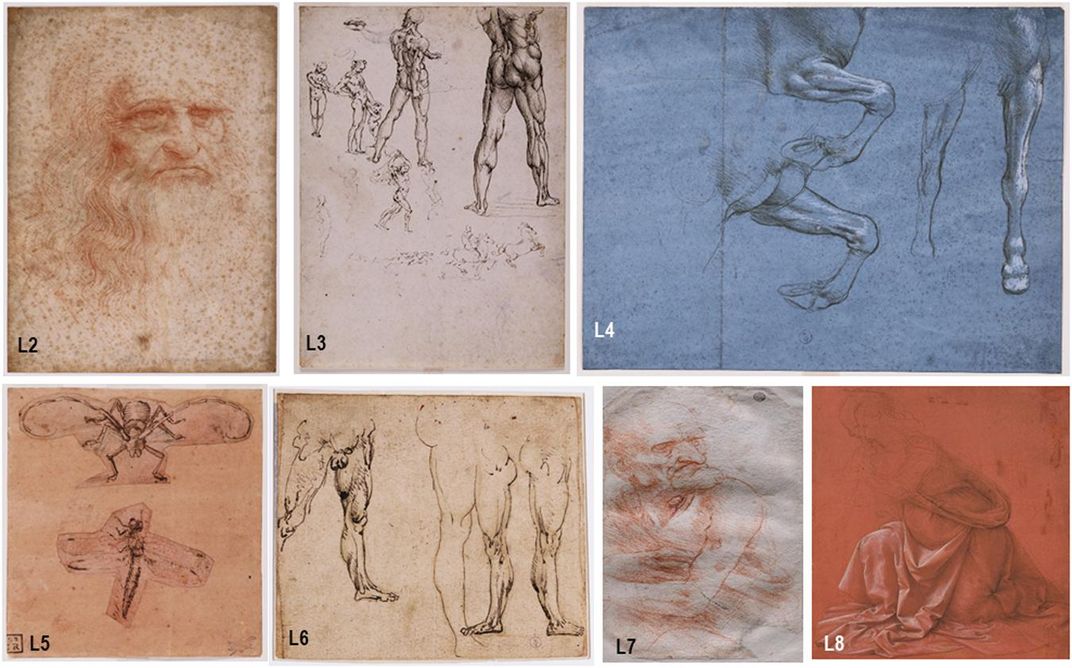

Researchers used new DNA sequencing technology to examine the “bio-archives” of seven of the Renaissance master’s sketches

:focal(906x663:907x664)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/71/56/71568228-8f60-4d38-ac53-6f22c096f80a/frontiers-microbiology-microbiome-original-artwork-leonardo-da-vinci.jpg)

Leonardo da Vinci produced a stunningly diverse oeuvre, from the Mona Lisa to codices discussing the possibility of human mechanical flight and groundbreaking anatomical sketches. But while the archetypal Renaissance man’s surviving works have been carefully preserved and studied for centuries, another Leonardo archive remains relatively unexplored: the troves of microbes and fungi that rest on the surfaces of his works, countless in number but invisible to the human eye.

A team of microbiologists in Italy and Austria recently took a closer look at the “bio-archive” that rests on seven of Leonardo’s 500-year-old sketches, reports Rafi Letzter for Live Science. Led by microbiologist Guadalupe Piñar of Vienna’s University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) and aided by new DNA sequencing technology, the researchers uncovered hidden traces left behind by curators—and even insects—on the priceless paper works over the centuries. The team published its findings this month in Frontiers in Microbiology.

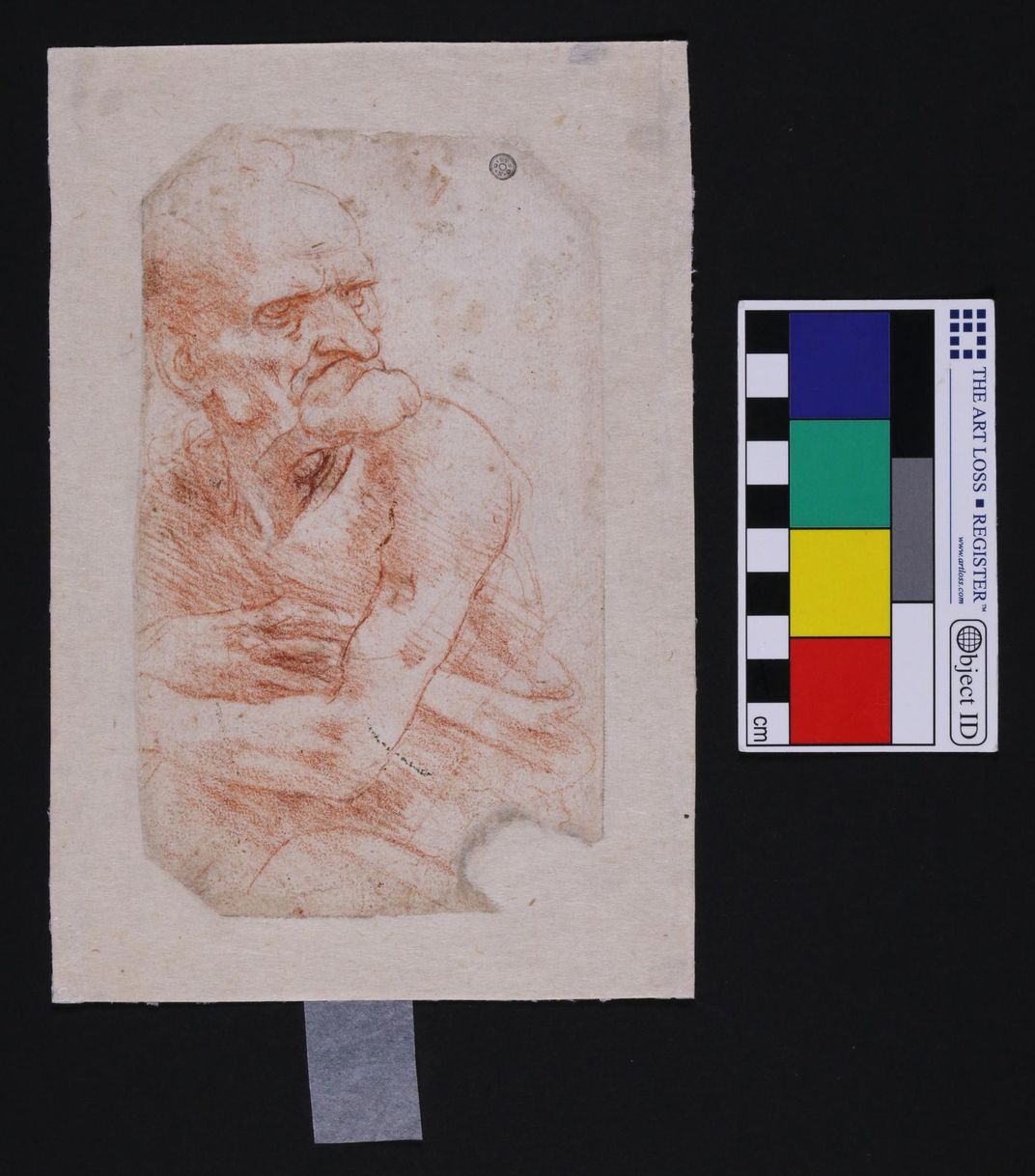

According to Matt Simon of Wired, the researchers studied five sketches held in the Royal Library of Turin and two from the Corsinian Library in Rome, including Autoritratto (also known as Portrait of a Man in Red Chalk, the work is widely thought to be a self-portrait in the artist’s old age) and Uomo della Bitta. Because the drawings are extremely delicate, the team carefully dabbed their surfaces with sterile membranes made of cellulose nitrate and used gentle suction tubes to remove microbes without damaging the paper.

Scientists then processed the samples using “nanopore” genetic sequencing, a new tool developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies that can exploit relatively tiny samples of DNA to identify a large number of microbes.

“In any other environmental study, you can go there, you can take kilos of soil or liters of water. But we cannot take samples,” Piñar explains to Wired. “So we have to live with these tiny samples that we get to obtain all the information.”

To their surprise, the researchers found that bacteria, not fungi, dominated the microbiomes of the sketches’ surfaces. Strains identified on the drawings included several associated with the human gut, like Salmonella and E. coli, as well as bacteria typically found in the guts of fruit flies.

Per a statement, the findings led the team to suspect that bugs may have defecated on the works of art before their archives were upgraded to the sterile, laboratory-like standards of today. All told, the works remained quite well preserved over the years, save for some “foxing”—brown spots of discoloration that are typical on old paper, writes Matthew Taub for Atlas Obscura.

“As the drawings are nowadays conserved, there’s no way that insects can go in and, you know, make their things there,” Piñar tells Wired. “It is not possible anymore. So you have to think this could have come from the times when the drawings were not stored like they are now.”

Speaking with Michelangelo Criado of Spanish newspaper El País, Piñar clarifies that the microbes identified are not necessarily “alive,” since “DNA is not a guarantee of viability.” In other words, the scientists were able to identify the presence of bacteria and fungi, but not whether the samples were dead or alive.

The researchers didn’t examine whether any of the human DNA traces could have belonged to Leonardo himself. No reliable record of the artist’s genetic code exists, and the most likely explanation for the human DNA discovered on the sketches is that it came from individuals who restored the works over the years, according to Live Science.

Still, Piñar tells El País, intact DNA can survive for a very long time, so the possibility that some of the human DNA recovered from the works’ surfaces could belong to Leonardo “can’t be ruled out.”

Piñar says that once widely applied, her team’s technique could play a crucial part in art historical research. The microbiome profiles of Leonardo sketches from Turin and Rome most closely resembled the profiles of others from the same libraries, which indicates that researchers could one day draw on artworks’ microbiomes for clues to their provenance and geographical history.

Microbe analysis could also tip conservators off to the presence of a potentially threatening fungi that is not yet visible on the work’s surface, as Massimo Reverberi, a microbiologist at Rome’s Sapienza University who was not involved in the study, tells Wired.

“It's like saying, OK, there’s an army in your country that has a weapon, and it can use this weapon to spoil your—in this case—artifact,” Reverberi says. “And when there is a trigger—that could be global warming—it could start to do some of its spoiling activity.”

Half a millennium after his death, many mysteries about Leonardo’s art endure. Just last week, Italian scholar Annalisa Di Maria made headlines by asserting that a resurfaced red chalk sketch of Jesus Christ might be a study for the “true” Salvator Mundi. Though most scholars agree that Leonardo created a work titled Salvator Mundi in his lifetime, they disagree whether he created the controversial painting that sold at Christie’s in 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/6b/136b7ba4-820f-446d-982b-8b09389709af/frontiers-microbiology-dna-sampling-microbiome-drawings-leonardo-da-vinci-1.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)