A Modernist Sculpted Ceiling Was Uncovered in a U-Haul Showroom

The Isamu Noguchi work is being shown once again

For decades, a famed sculptor's work was hidden by one of the most mundane features of modern buildings: the drop ceiling. Now, after decades of lurking just out of sight, U-Haul has restored a sculpted ceiling designed by Isamu Noguchi that's been lying just out of sight in the company's St. Louis showroom.

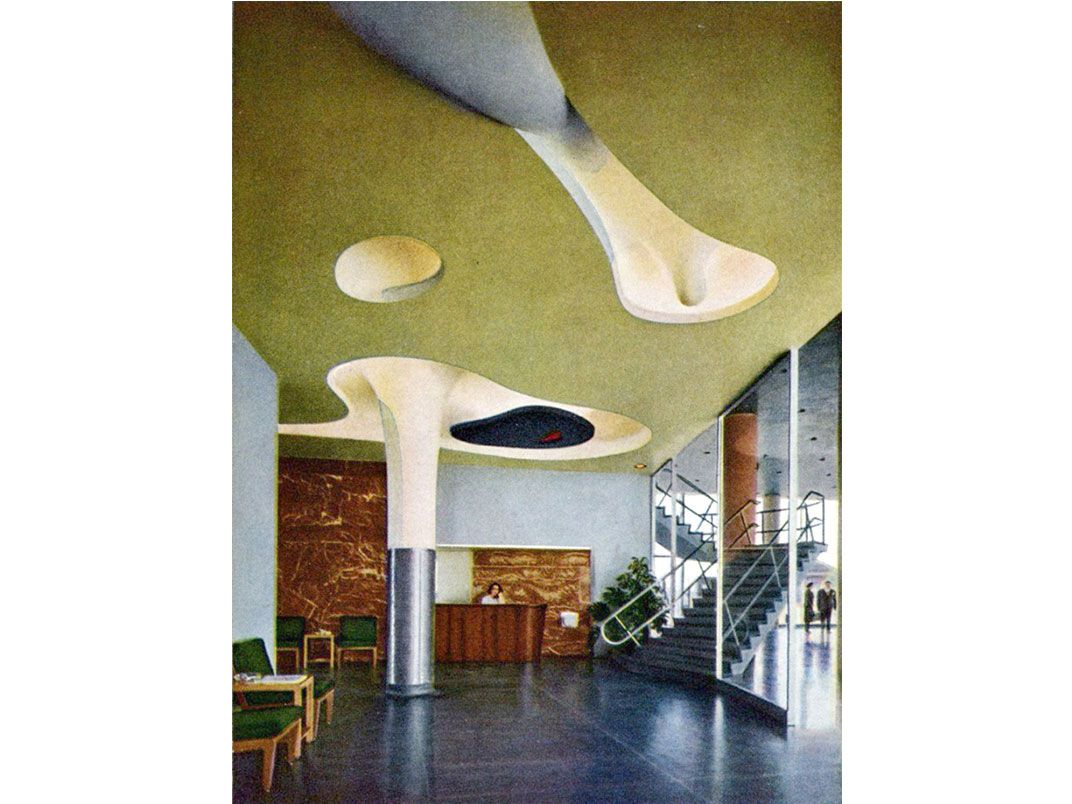

An acclaimed sculptor, Noguchi was known in the American art scene throughout the 20th century for his large-scale biomorphic sculptures and public works. In 1946, Noguchi was contracted to construct a custom lobby ceiling for the American Stove Company-Magic Chef Building, the brand-new St. Louis headquarters of the company, Robert Duffy and Kelly Moffitt report for St. Louis Public Radio. Nicknamed a “lunar landscape,” Noguchi’s sculpted ceiling featured undulating waves of plaster that hid light bulbs in its curving forms. The striking example of mid-century modern architecture was hidden away when the building was eventually acquired by U-Haul, which installed a drop ceiling during the 1990s, covering the work.

For years, the few people who remembered Noguchi’s lost ceiling assumed that it had been destroyed or damaged beyond repair. However, during a recent renovation of the lobby, U-Haul decided to reveal and restore the long-lost sculpture to its original state, Eve Kahn reports for the New York Times. Now, for the first time in decades, the last surviving example of Noguchi’s “lunar landscapes” is back on display.

"Visually striking and fundamentally practical, the plaster ceiling's undulating curves, characteristic of Noguchi's biomorphic sculpture of the 1940s, provided discreet signage, lighting, and a welcome burst of color for visitors,” Genevieve Cortinovis, the St. Louis Art Museum’s assistant curator of decorative arts and design said in a statement, Amah-Rose Abrams reports for artnet News. "Noguchi held that by lending punctuation and dimension to space, these large-scale sculptures, an extension of the architecture itself, could make people 'feel better, feel happier to be there.'"

While the work was largely forgotten by the public, curators had puzzled over how to handle the artwork for years. As David Conradsen, Cortinovis’ co-curator at the St. Louis Art Museum, tells Kahn, several experts had considered ways of removing the ceiling and transplanting it to the museum. They abandoned the plan, though, after they deemed that it would be too risky to try to move the sculptural structure.

“It would be basically destroyed in removal,” as Conradsen tells Kahn.

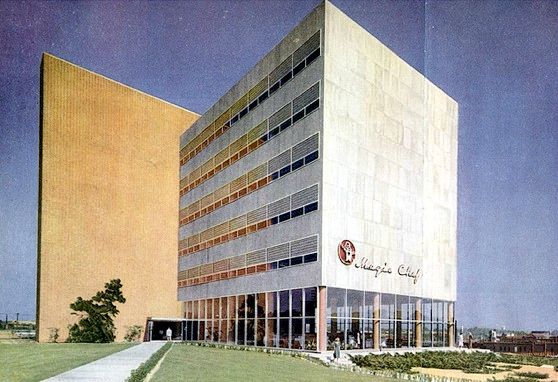

The ceiling isn’t the only feature of note. The building itself was designed by the architect Harris Armstrong, who left his mark on many buildings in mid-century St. Louis. While its interiors were altered to serve U-Haul’s need for storage facilities, its exterior is still mostly the same as when Armstrong first designed it and includes a bold brickwork facade reminiscent of the city’s prevailing architectural style, Duffy and Moffitt write.

Now that the renovations and restorations are complete, U-Haul is welcoming the public to come into the showroom to see the surviving structure. While anyone is welcome to come during business hours, U-Haul is hosting a community open house to view Noguchi’s restored work on May 19 at 7 P.M.