Why the First Monument of Real Women in Central Park Matters—and Why It’s Controversial

Today, New York City welcomed a public artwork honoring three suffragists. But some scholars argue that the statue obscures more than it celebrates

:focal(3274x1496:3275x1497)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7b/b4/7bb43928-545b-43a1-b853-591181f1cee1/gettyimages-1268825339.jpg)

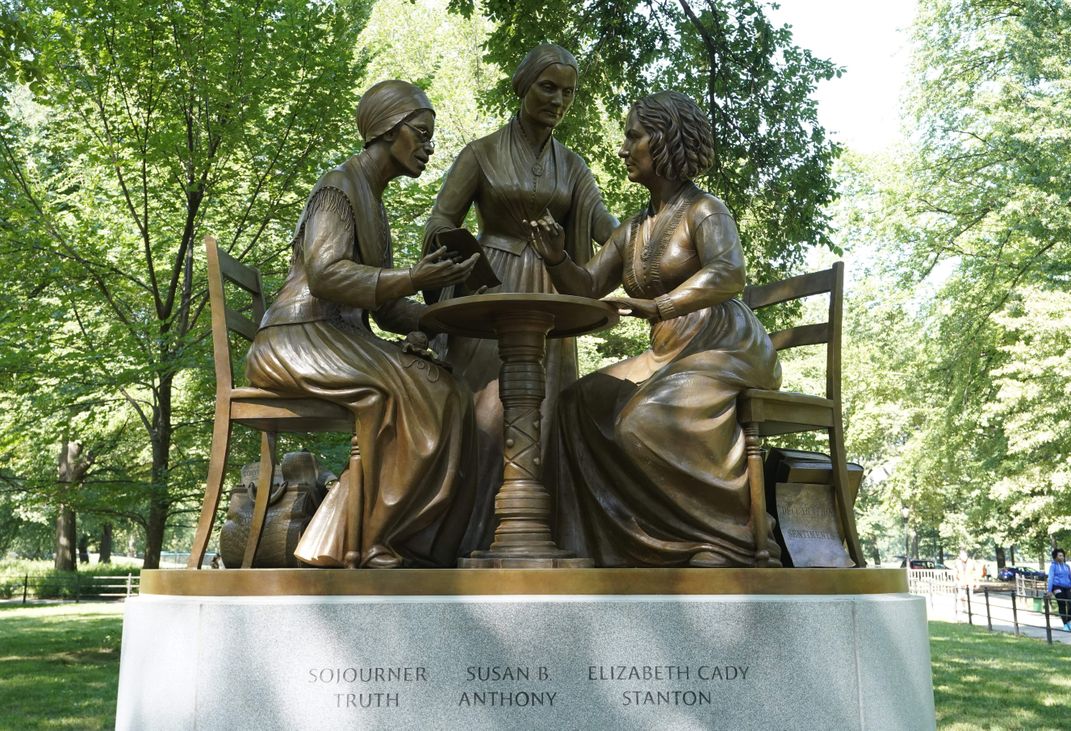

On Wednesday, a 14-foot-tall bronze statue depicting famed suffragists Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton made its debut in New York City’s Central Park. The monument is the first sculpture of real women—several statues honor such fictional figures as Alice in Wonderland, Juliet and Mother Goose—installed in the park’s 167-year history.

“You’ve heard of breaking the glass ceiling,” Meredith Bergmann, the artist who designed the statue, tells CNN. “This sculpture is breaking the bronze ceiling.”

Unveiled in a livestreamed ceremony featuring suffragist writings recited by actors Viola Davis, Meryl Streep and America Ferrera, as well as an in-person address by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument has been in the works since 2014. Today’s ceremony was planned to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which enfranchised many—but not all—American women upon its August 18, 1920, ratification.

The nonprofit Monumental Women organization, also known as the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Statue Fund, launched its campaign in response to the overwhelming number of public works centered on white men. As reported in the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s 2011 Art Inventories Catalog, just 8 percent of the 5,193 public outdoor sculptures then scattered across the country depicted women.

According to Alisha Haridasani Gupta of the New York Times, the “journey from concept to creation” has been a “long and winding one,” with numerous scholars and writers criticizing the project’s alleged whitewashing of black suffragists’ contributions to the movement. In recent months, the debate has taken on increased urgency as communities reckon with the racist, colonialist legacies of public monuments in their shared spaces.

Widespread criticism had led Bergmann to revise the sculpture’s design several times, reported Zachary Small for Hyperallergic last year. The original proposal showed Stanton and Anthony standing near an unfurled scroll bearing the names of 22 other women suffragists, including Truth, Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells. But after members of the public—among them feminist activist Gloria Steinem, who told the Times’ Ginia Bellafante that the layout made it seem as if Stanton and Anthony were “standing on the names of these other women”—objected, the scroll was removed.

Later in 2019, Brent Staples, an editorial writer for the Times, criticized the planned sculpture for presenting a “lily-white version of history.” Solely featuring Stanton and Anthony in a monument dedicated to the entire suffrage movement would “make the city seem willfully blind to the work of black women who served at the vanguard of the fight for universal rights—and whose achievements have already shaped suffrage monuments in other cities,” he added.

Staples and other critics argue that the statue glosses over Stanton and Anthony’s own beliefs on race, as well as the racism that black suffragists faced within the movement.

As Brigit Katz points out for Smithsonian magazine, no black women attended the Seneca Falls convention. And in 1913, white suffragists reportedly instructed black activists to walk in the back of a women’s march on Washington. According to the NAACP’s journal, Crisis, “telegrams and protests poured in” following initial attempts to segregate marchers, “and eventually the colored women marched according to their State and occupation without let or hindrance.”

Stanton and Anthony were two of the many wealthy white women who argued that their enfranchisement should take precedence over that of African American men. Although the pair had collaborated with Frederick Douglass closely on various abolitionist endeavors, their friendship soured when Stanton and Anthony refused to support the 15th Amendment. Per the National Park Service, the women took issue with the legislation, which was ratified in 1870, because it enfranchised black men before white women they believed were more qualified to vote.

In 1866, after Douglass reportedly said he viewed voting rights as “vital” for black men and “desirable” for women, Anthony replied, “I will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work for or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.”

Stanton, meanwhile, “stands for an impoverished vision of equality that never admitted that black Americans, male and female, were her equals,” wrote historian Martha S. Jones—who previously chronicled the history of black suffragists for Smithsonian—in a 2019 Washington Post op-ed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/24/17/24171e05-0c0d-4b38-9fee-536fa4559e90/truthr.jpg)

Issues of race proved central to Congressional debates over the 19th Amendment. As historian Kimberly Hamlin wrote in a 2019 Washington Post op-ed, senators arguing against the amendment cited “states’ rights, their hatred of the 15th Amendment and their desire to keep African Americans from the polls” as their primary reasons for opposing the law.

White leaders feared that the amendment would force the government to enforce the 15th Amendment, which enfranchised African American men, in addition to encouraging African American women to vote.

“By the 1910s, many white suffragists had come to believe that focusing on white women voting was the only way they could get the 19th Amendment through Congress,” Hamlin explains.

Speaking with Jessica Bliss and Jasmine Vaughn-Hall of USA Today, historian Carole Bucy says that white suffragists essentially ensured the amendment’s passage by telling Southern legislators, “Look there are already laws that keep African American men from voting. Those will still be intact. So if you are afraid women voting will bring in all these black people voting, it won’t.”

Ahead of the Central Park sculpture’s unveiling, Myriam Miedzian, a writer, public philosopher and activist who serves on Monumental Women’s Board of Directors, defended Anthony and Stanton in a Medium blog post headlined “The Suffragists Were Not Racists: So Cancel the Cancel Culture and Celebrate An Accusation Free Suffrage Centennial.”

“U.S. history is tainted by the rabid racism of prominent politicians, [S]upreme [C]ourt justices, and organizations. Stanton, Anthony, and the Suffrage movement do not belong on this list, or even in its vicinity,” Miedzian said. “This is not to deny that there were racist suffragists, especially in the South. How could there not be during a deeply racist historical period. Nor is it to deny that after the Civil War, Stanton and Anthony used some racist language. But it is to deny that these characteristics were in any way universal or dominant.”

Last August, in response to widespread criticism, Monumental Women announced plans to add Truth—the abolitionist and suffragist perhaps best known for her groundbreaking “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech—to the sculpture.

Originally, Bergmann’s design depicted Truth sitting at a table next to Stanton and Anthony with her hands resting in her lap. When some criticized the statue for portraying Truth as “merely listening” to the suffragists, the sculptor updated Truth’s body language to make her a more “active participant” in the scene, writes Erin Thompson for the Nation.

Monumental Women maintains that the three suffragists would have worked together during their lifetimes, making it reasonable to depict them gathered around a table.

“They all were contemporaries,” the nonprofit’s president, Pam Elam, tells CNN. “They all did share a lot of the same meetings and speech opportunities. They were on the same stages, so why not have them all on the same pedestal.”

After the updated design was announced last summer, a group of more than 20 leading academics penned an open letter outlining their lingering concerns with the monument.

“If Sojourner Truth is added in a manner that simply shows her working together with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Stanton’s home, it could obscure the substantial differences between white and black suffrage activists, and would be misleading,” wrote the signatories, who included Todd Fine, president of the Washington Street Advocacy Group; Jacob Morris, director of the Harlem Historical Society; and Leslie Podel, creator of the Sojourner Truth Project.

“While Truth did stay at Stanton’s home for one week to attend the May 1867 meeting of the Equal Rights Association, there isn’t evidence that they planned or worked together there as a group of three,” the letter—published in its entirety by Hyperallergic—continued. “Additionally, even at that time, Stanton and Anthony’s overall rhetoric comparing black men’s suffrage to female suffrage treated black intelligence and capability in a manner that Truth opposed.”

Historian Sally Roesch Wagner tells the Nation that she believes monuments to individuals meant to celebrate the feminist movement “are a standing historic lie,” as no single individual or group of individuals brought about the 19th Amendment.” Instead, says Wagner, women’s rights have been won “by a steady history of millions of women and men … working together at the best of times, separately at the worst.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/df/66df67ea-5e7d-401e-93b6-9b40cd75b5a3/da4_7035_082620_womens_rights_monument_cp.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d4/86/d48662bf-0019-4107-8d51-ae8806073fe8/da5_3933_082620_womens_rights_monument_cp.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nora.png)