A New Museum of West African Art Will Incorporate the Ruins of Benin City

Designed by architect David Adjaye, the museum will reunite looted artifacts currently housed in Western institutions

:focal(407x293:408x294)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/94/dd/94ddfe59-d2e9-4c0c-a73f-a067022fbdb1/view_of_museum.jpg)

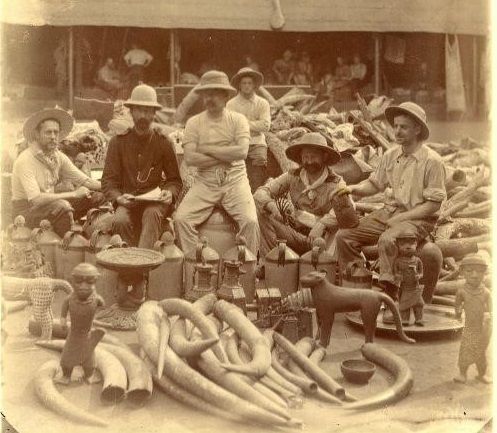

In January 1897, British troops attacked the Kingdom of Benin’s capital in what is now southern Nigeria, exiling the Edo people’s ruler, destroying much of the city and stealing its treasures. More than a century later, the Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA)—a planned cultural institution set to be built on the site of the razed city—promises to not only restore some of Benin City’s ruins to their former glory but also act as a home for the array of looted artifacts being returned to Nigeria by museums around the world.

As Naomi Rea reports for artnet News, the British Museum, home to the world’s largest collection of Benin Bronzes, will help archaeologists excavate the site as part of a $4 million project slated to start next year. Objects discovered during the dig will become part of the new museum’s collections.

EMOWAA’s future home is located in the heart of the old city, next to the palace of the oba, or king, of Benin, which was rebuilt in the 20th century following its destruction in the 1897 attack. Ghanaian-British architect David Adjaye, who previously designed the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History, plans to incorporate Benin City’s surviving walls, moats and gates into the new building.

“From an initial glance at the preliminary design concept, one might believe this is a traditional museum but, really, what we are proposing is an undoing of the objectification that has happened in the West through full reconstruction,” says Adjaye in a statement released by his firm, Adjaye Associates.

The Legacy Restoration Trust, a Nigerian nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting the country’s cultural heritage, is helping to lead the project. Per the statement, the building, which will draw inspiration from Benin City’s historical architecture, will feature a courtyard with indigenous plants and galleries that “float” above the gardens. The museum’s design will echo the shape of the precolonial palace, complete with turrets and pavilions, Adjaye tells the New York Times’ Alex Marshall.

According to a British Museum blog post, EMOWAA aims to reunite loaned “Benin artworks currently within international collections” while investigating the broader histories represented by these artifacts. The museum will feature “the most comprehensive display in the world of Benin Bronzes, alongside other collections.”

Created as early as the 16th century, the Benin Bronzes were the work of artisan guilds employed by Benin City’s royal court. Some of the brass-and-bronze sculptures were used in ancestral altars for past royal leaders. Others decorated the royal palace, documenting the kingdom’s history.

During the destruction of the city in 1897, British soldiers and sailors looted the bronzes, the majority of which ended up in museums and private collections, writes Mark Brown for the Guardian. The British Museum—also home to the Elgin Marbles, a contested collection of classical sculptures removed from the Parthenon—owns more than 900 Benin Bronzes.

According to Catherine Hickley of the Art Newspaper, the London cultural institution is one of several museums involved in the Benin Dialogue Group, a consortium convened to discuss the looted artifacts’ fate. In 2018, members pledged to loan a rotating selection of these objects to the Nigerian museum, then tentatively titled the Benin Royal Museum.

Architectural Record’s Cathleen McGuigan aptly summarizes the arrangement, writing, “The plans for the museum will doubtless further pressure Western institutions to return Benin’s patrimony—though most are not committing to permanently giving back looted pieces but lending them.”

The Edo people of southern Nigeria founded the Kingdom of Benin in the 1200s. Benin became a trading power, selling artwork, gold, ivory and pepper to other countries. It was also involved in the slave trade. During the 19th century, civil wars and British encroachment on Benin’s trading networks weakened the nation’s power. After burning Benin City in 1897, the British claimed the kingdom’s territory and incorporated it into British Nigeria, which gained independence as the nation of Nigeria in 1960.

In addition to housing historical artwork and artifacts, the museum will feature a space for contemporary art. Speaking with the Times, Adjaye says he hopes the institution will help connect local residents with their cultural heritage and support “a renaissance of African culture.”

He adds, “It has to be for the community first, and an international site second.”

Adjaye tells the Times that he expects the museum to be completed in about five years. He says the institution will create the infrastructure and expertise required to handle artwork and cultural objects, which he expects museums in Europe and elsewhere will eventually return.

“Restitution has to happen, eventually,” he says. “The objects need to be returned. In the 21st century, this is no longer a discussion.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Livia_lg_thumbnail.png)