How Japanese Artists Responded to the Transformation of Their Nation

Two new exhibitions at the Freer|Sackler vividly illustrate Japan’s arrival to the modern age

Not long after Japan formally decided to start trading with the West in the 1850s, photography also came to the island nation. Both signaled a new era of modernity.

The quest to understand and depict the soul of Japan as it evolved from Imperialist, agrarian and isolationist, to more populist, global and urban is the theme of two exhibitions now on view at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C. The two shows, “Japan Modern: Photography from the Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck Collection” and “Japan Modern: Prints in the Age of Photography,” share much, says Frank Feltens, curator of the print show.

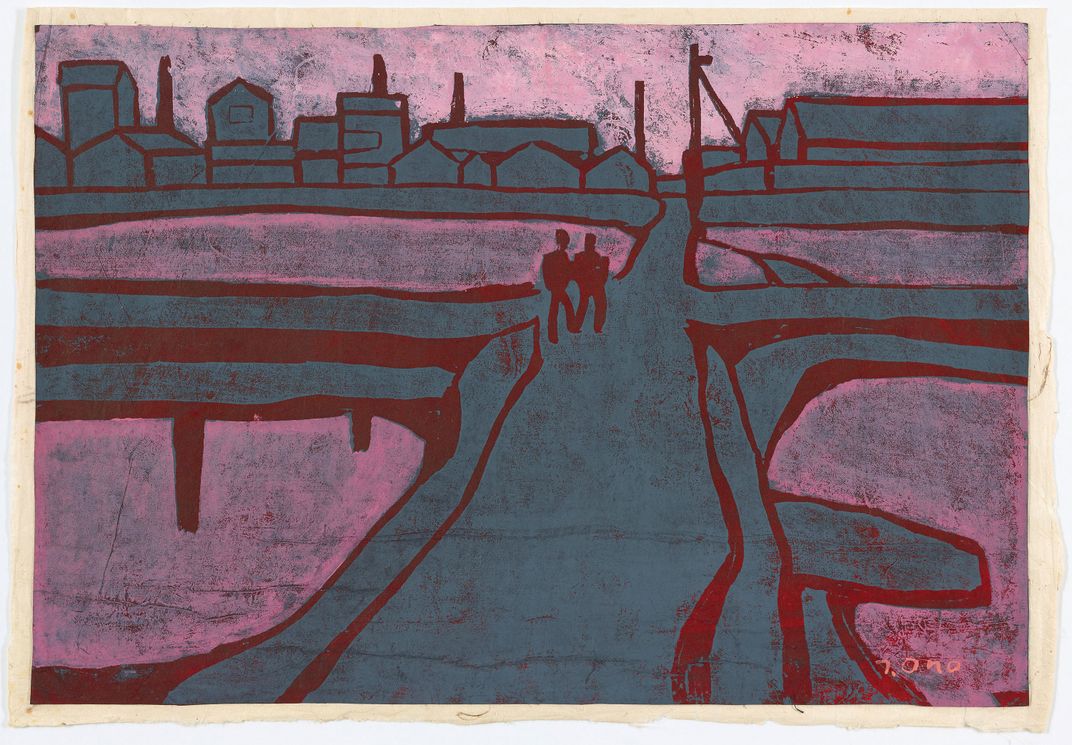

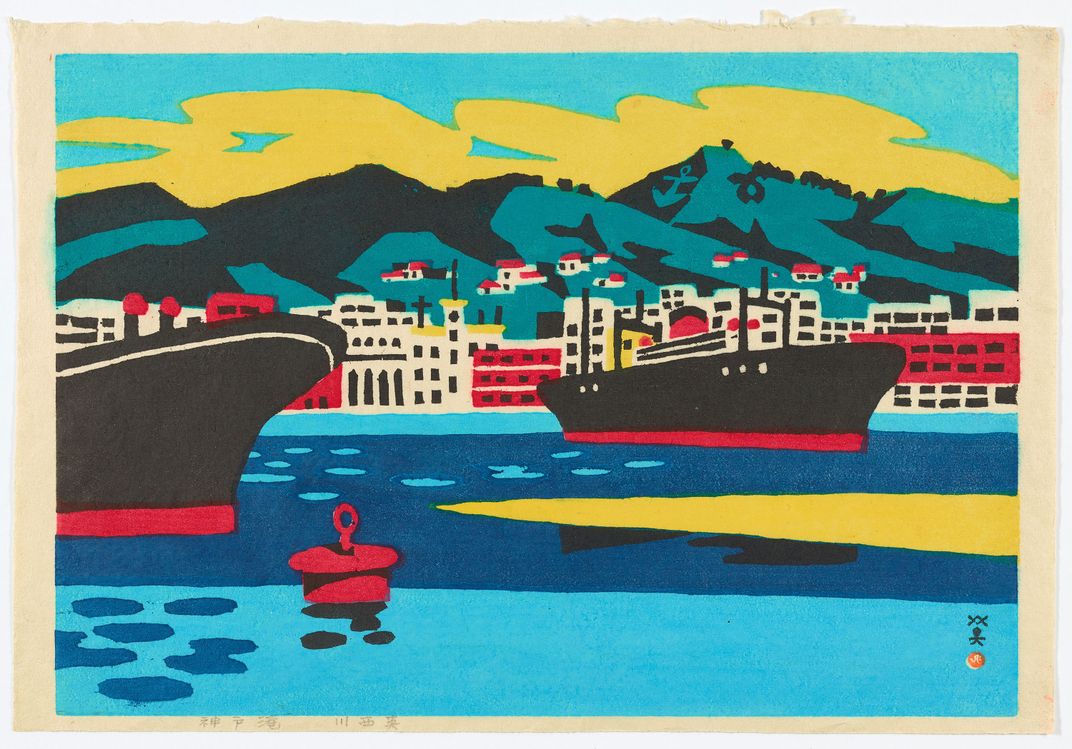

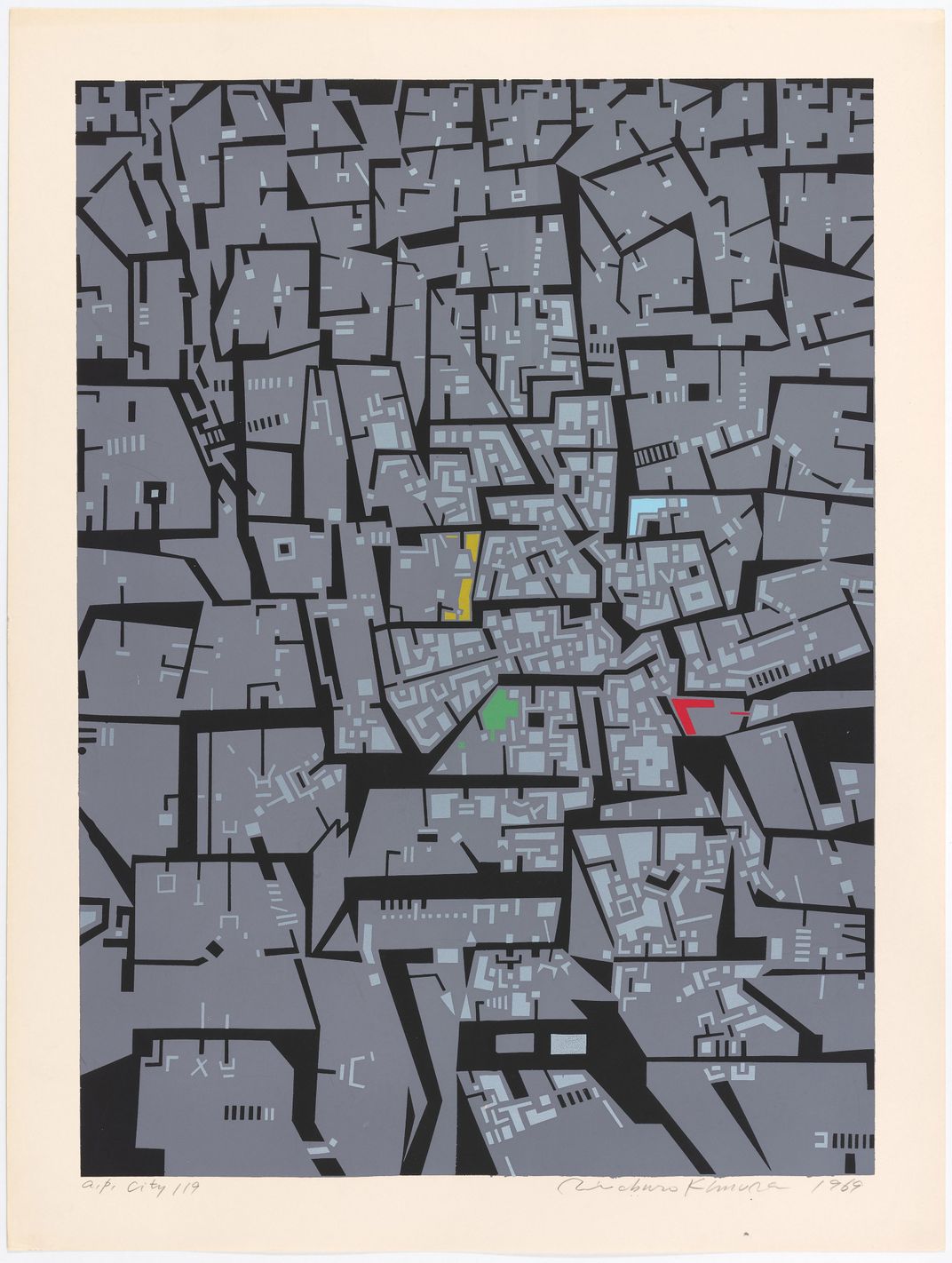

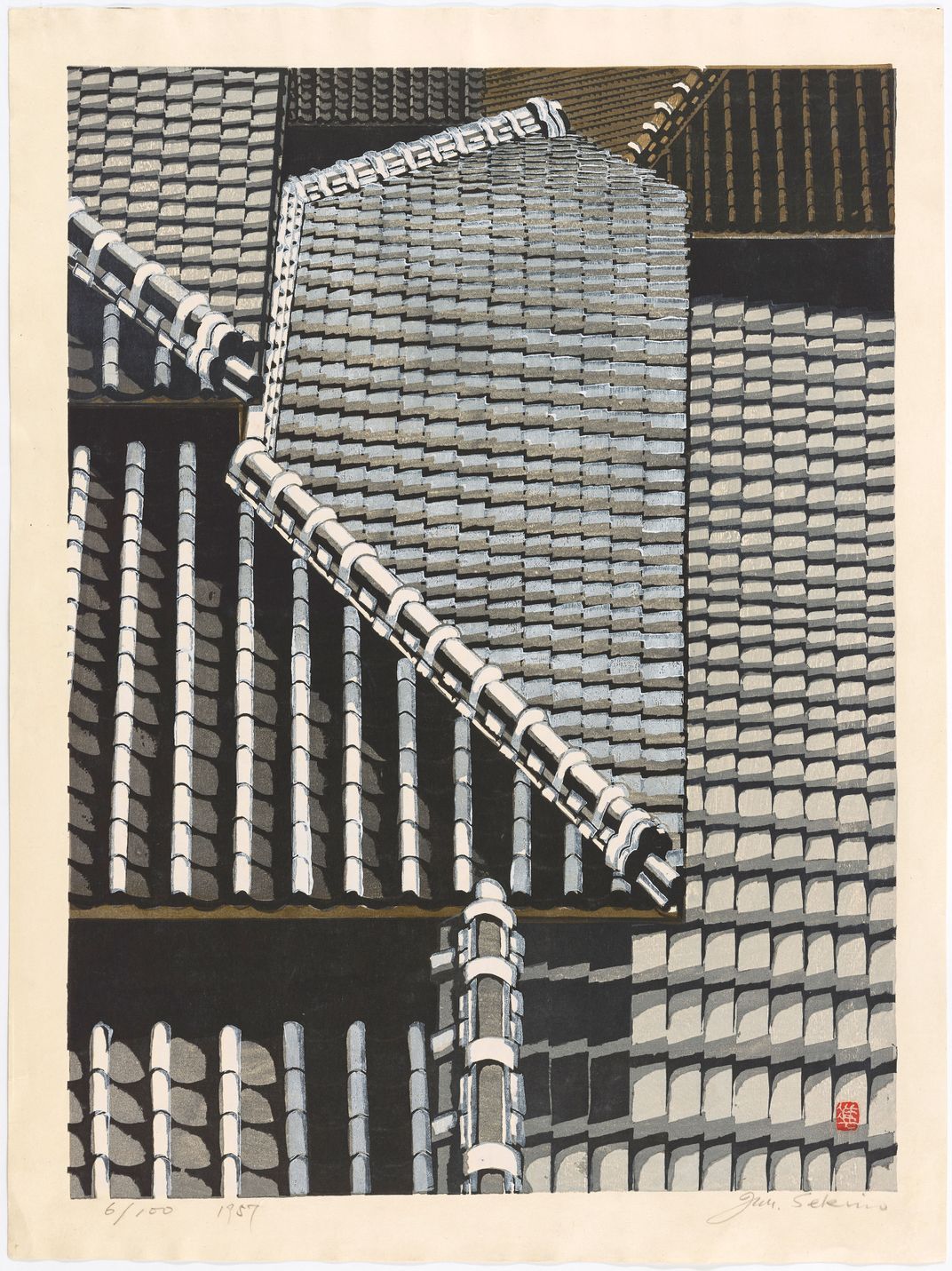

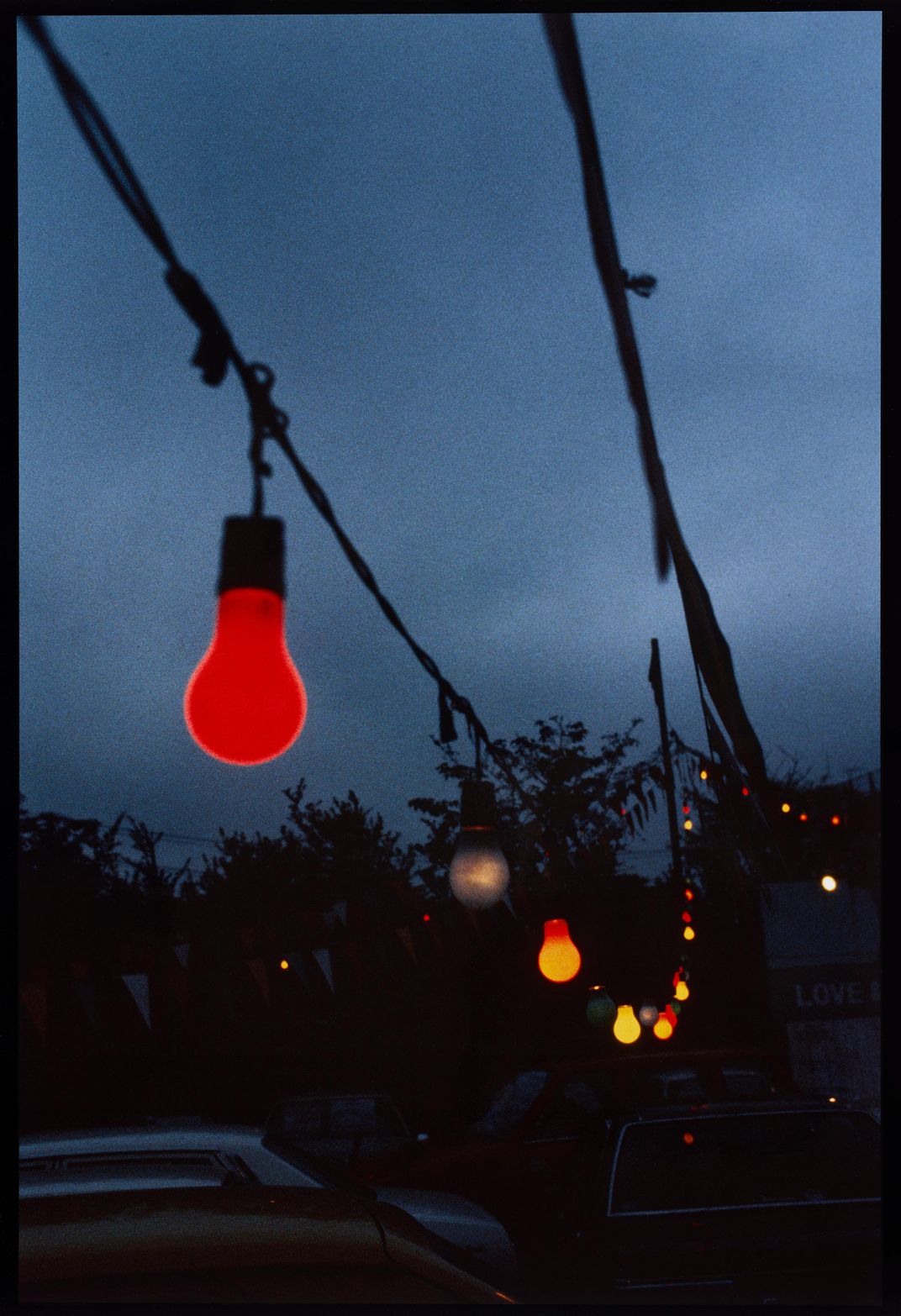

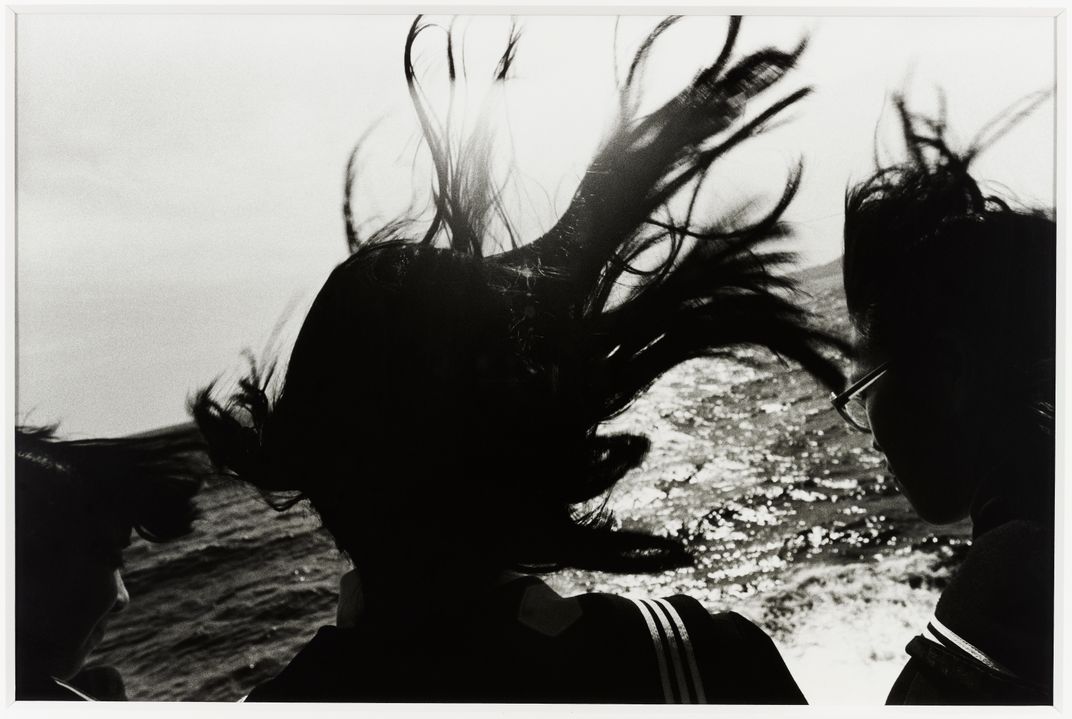

Neither are in chronological order, but both group images in common themes—with city and country dominating. The photography show is highly documentary; many are in black and white. The prints, made with carved wood blocks, are bold, visual and colorful. But, says Feltens, “between the two shows, you start finding more and more commonalities”—an interest in surfaces, angles, fragments.

The artists are “looking at the world outside, but reimagining it through one time, the lens and then through the wood blocks,” Feltens says.

As it did in the Western world, photography cast a large shadow. Wood block prints had been around for at least a millennium, primarily as a means of communicating something about the culture—telling stories. By the late 19th century, printmaking was dead—a casualty of the easier, cheaper photography.

The first known photograph taken in Japan dates to 1848, says Feltens. Daguerrotypes were popular in Japan—as they were in Europe and America—but photography really took off in the 1920s, with the rise of more portable equipment like Kodak’s vest pocket camera, says Carol Huh, curator of the photography show. The vest pocket, which is about the size of a modern camera, with a lens that pulls out, accordion style, was made between 1912 and 1926, and became extremely popular in Japan, giving rise to camera clubs and the Besu-Tan School photographic style.

The photo show was made possible by the partial gift in May 2018 of a trove of some 400 photographs collected by Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, Japan aficionados and screenwriters, best known for American Graffiti and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The collection had largely been displayed on the walls of their Brentwood, California, home. Huh selected for the show 80 prints from two dozen artists, focusing on those that influenced the trajectory of Japanese photography.

The initial gallery—with prints from the 1920s and 1930s—shows how Japanese photographers were so keenly influenced by European contemporaries, especially the soft-focus pictorialists. “We’re hitting a kind of peak of affirming photography as a medium of expression—an art medium, and also a transition towards a more modernist aesthetic,” says Huh. Early photos documented the city and country—a canal; wheat waving in the breeze. The transition is seen in Ishikawa Noboru’s 1930s-era light-and-shadow study, Barn Roof, which hones in on a fragment of a cupola with a misty background.

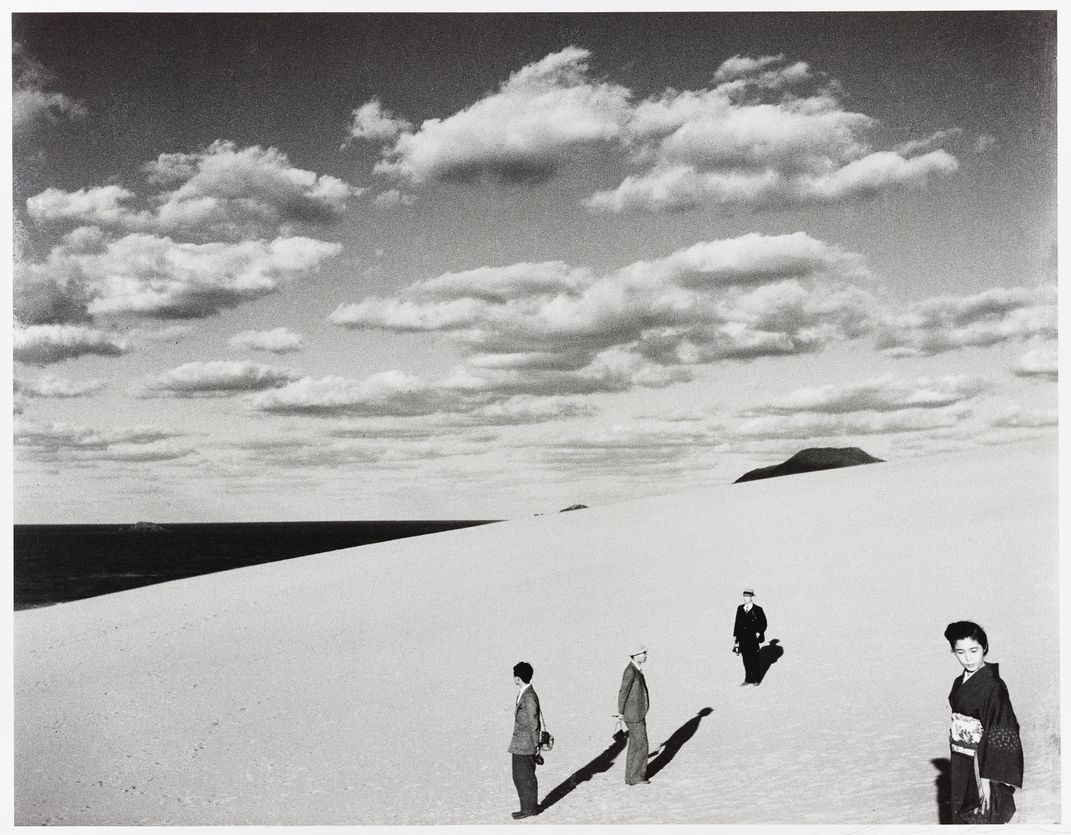

An Afternoon on the Mountain, a 1931 gelatin silver print by Shiotani Teiko, could be an abstract painting. A lone, tiny skier looks to be fighting his way up the sharply angled gray slope that slashes across the bottom quarter of the photograph, dividing it from the equally gray sky. Teiko largely shot in Tottori Prefecture on Japan’s western coast, creating from its huge dunes and mountains. “The landscape becomes an opportunity for these studies of form,” says Huh.

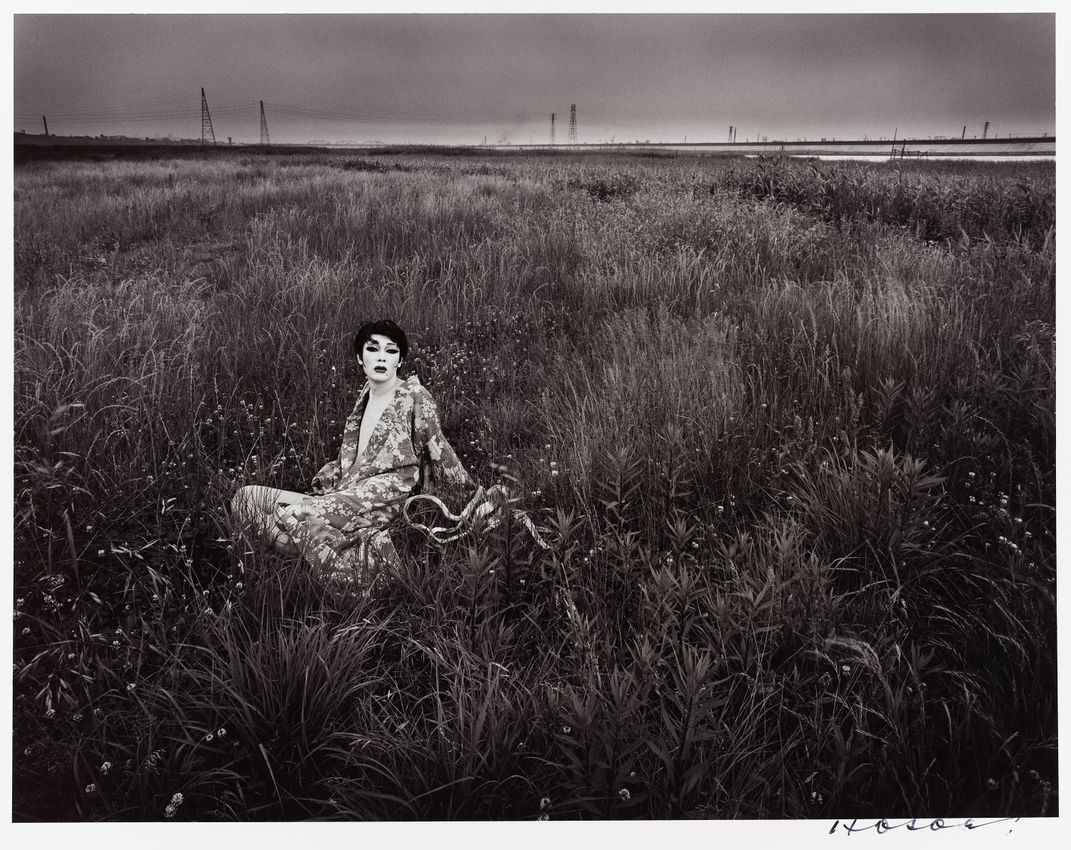

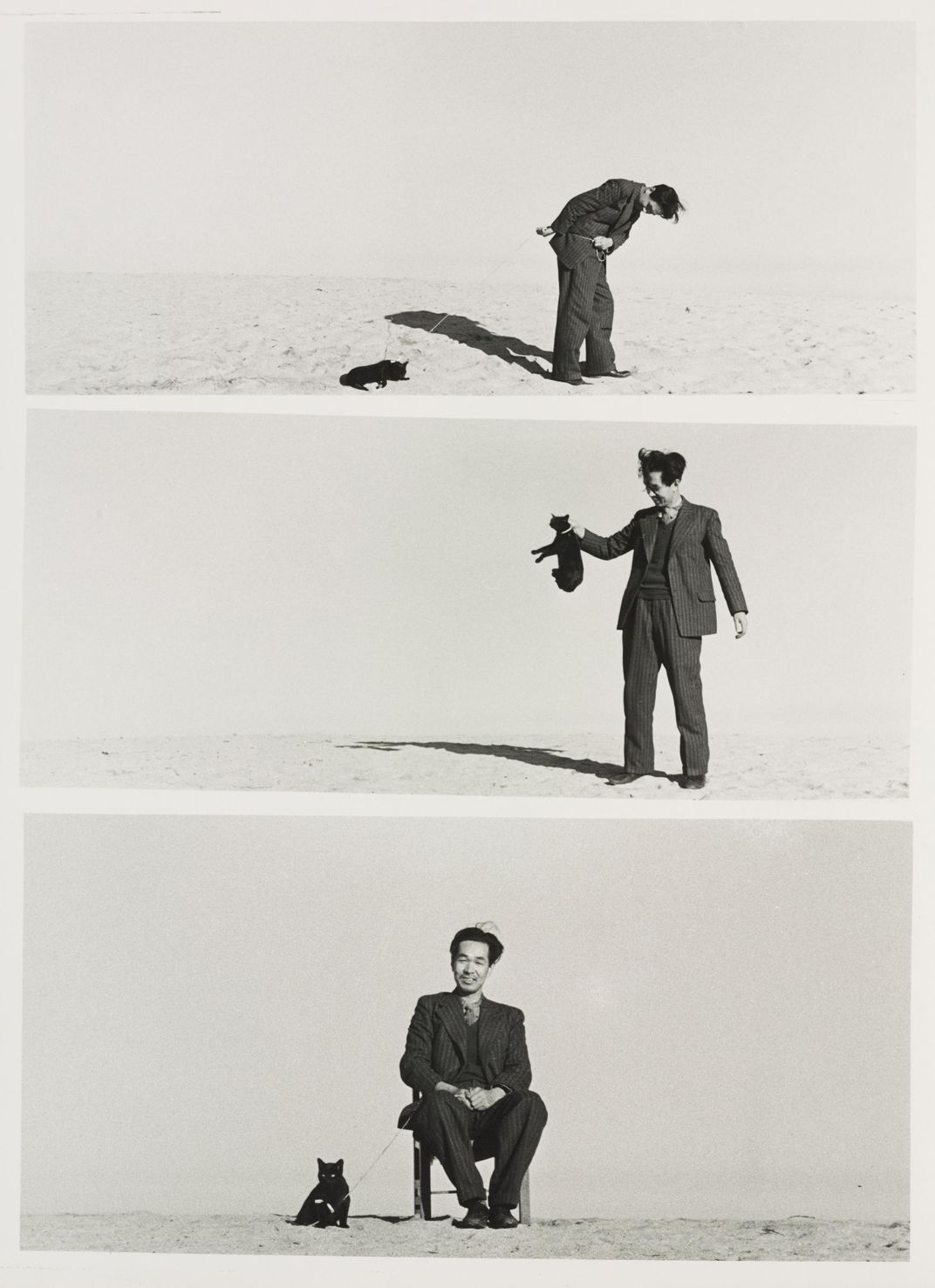

Teiko also shot whimsical prints of unnaturally bent objects—a precursor to the surrealism that became so evident in his student Ueda Shoji’s work. Shoji’s 1950 My Wife on the Dunes features his kimono-clad spouse, cut off at the knees, staring from the right foreground; to her right, stand three men in business suits, facing in different directions with huge shadows looming behind each. Surreal-like, it also depicts a Japan co-existing with its ancient heritage and its modern imagery.

Many of the photos examine that interplay, especially as Japan looked inward and faced the reality of the devastation of World War II and how the country would rebuild and remake itself.

Japan is the only nation to ever have experienced the wrath of an atomic bomb. The show touches on Nagasaki, where the Americans dropped a bomb on the town of 200,000 at 11:02 a.m. on August 9, 1945. Japan barred photography in the aftermath of both Nagasaki and Hiroshima, but some 16 years later—in 1961—the Japan Council Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs commissioned Tomatsu Shomei to document the city’s recovery. “It was not unusual at the time for many Japanese not to have seen actually what happened there,” says Huh. That included Shomei. He delved into Nagasaki’s fabric, photographing current life, bomb survivors and objects at what is now the Atomic Bomb Museum.

One of those, shot on a simple background: a wristwatch stopped at 11:02. A bottle that was distorted by the blast takes on a disturbingly human form. “It looks like a carcass,” says Huh. Shomei’s book 11:02 Nagasaki is a personal reckoning and a key document of that horrific event.

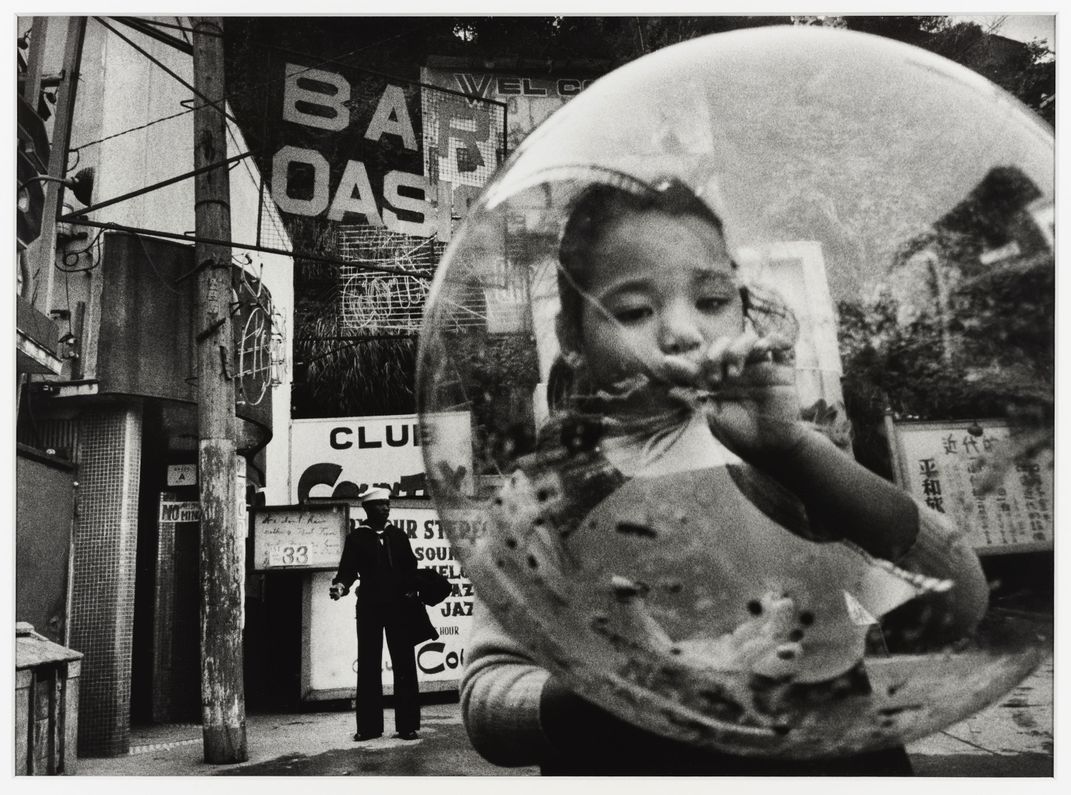

He was also obsessed with—and photographed his take on—the Americans’ post-war occupation of Japan, which officially ended in 1952. The effects, however, were lasting. Many of the images show photographers’ curiosity and dismay with these foreigners who had inserted themselves into their nation. The show includes some prints from Yamamura Gasho’s 1959-62 series on Washington Heights, an American military residential area in Tokyo. In one, a group of mischievous-looking black and white children press up against a chain link fence. Gasho is literally “outside the fence looking in at this strange transplant in the middle of Tokyo,” says Huh.

The show ends with the 2009 Diorama Map of Tokyo, a modernist collage by Nishino Sohei, a 36-year-old artist. He walked Tokyo, snapping street views, echoing a similar project from the late 19th century that created the first measured maps of Japan. Sohei cut out tiny prints from contact sheets, laid them down next to each other and then photographed them again for the final print. “The act of putting them together is remembering that journey,” says Huh.

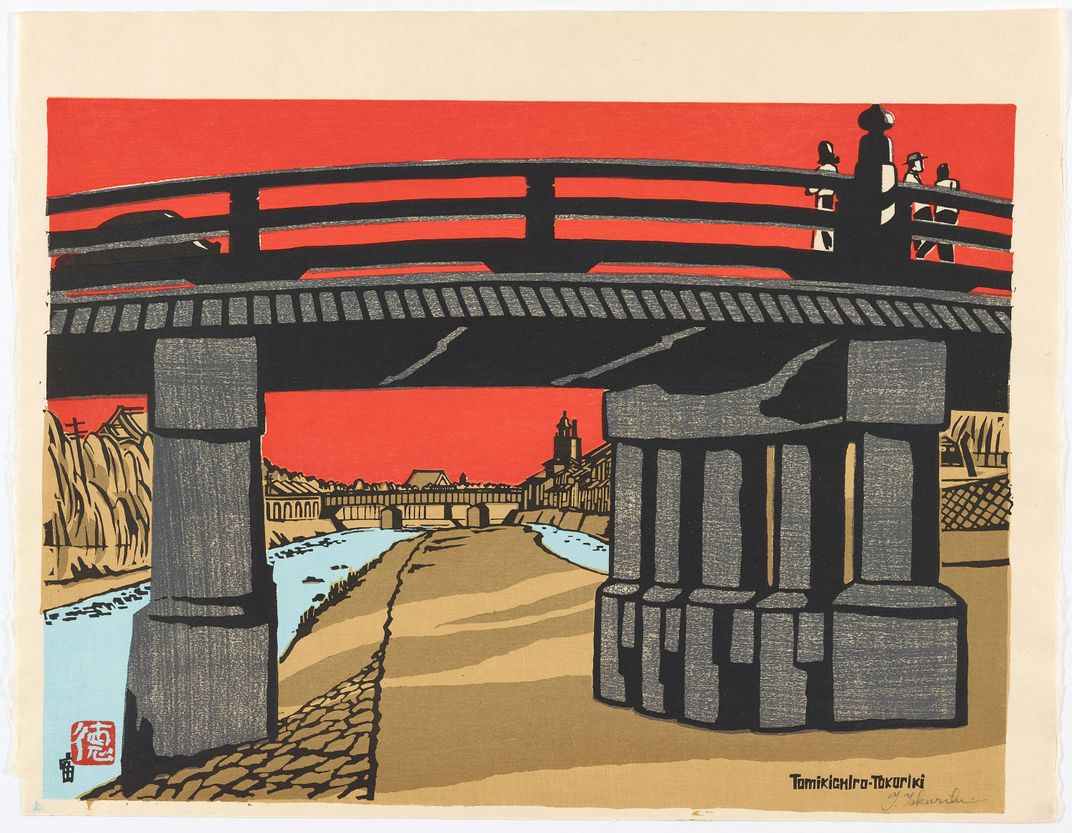

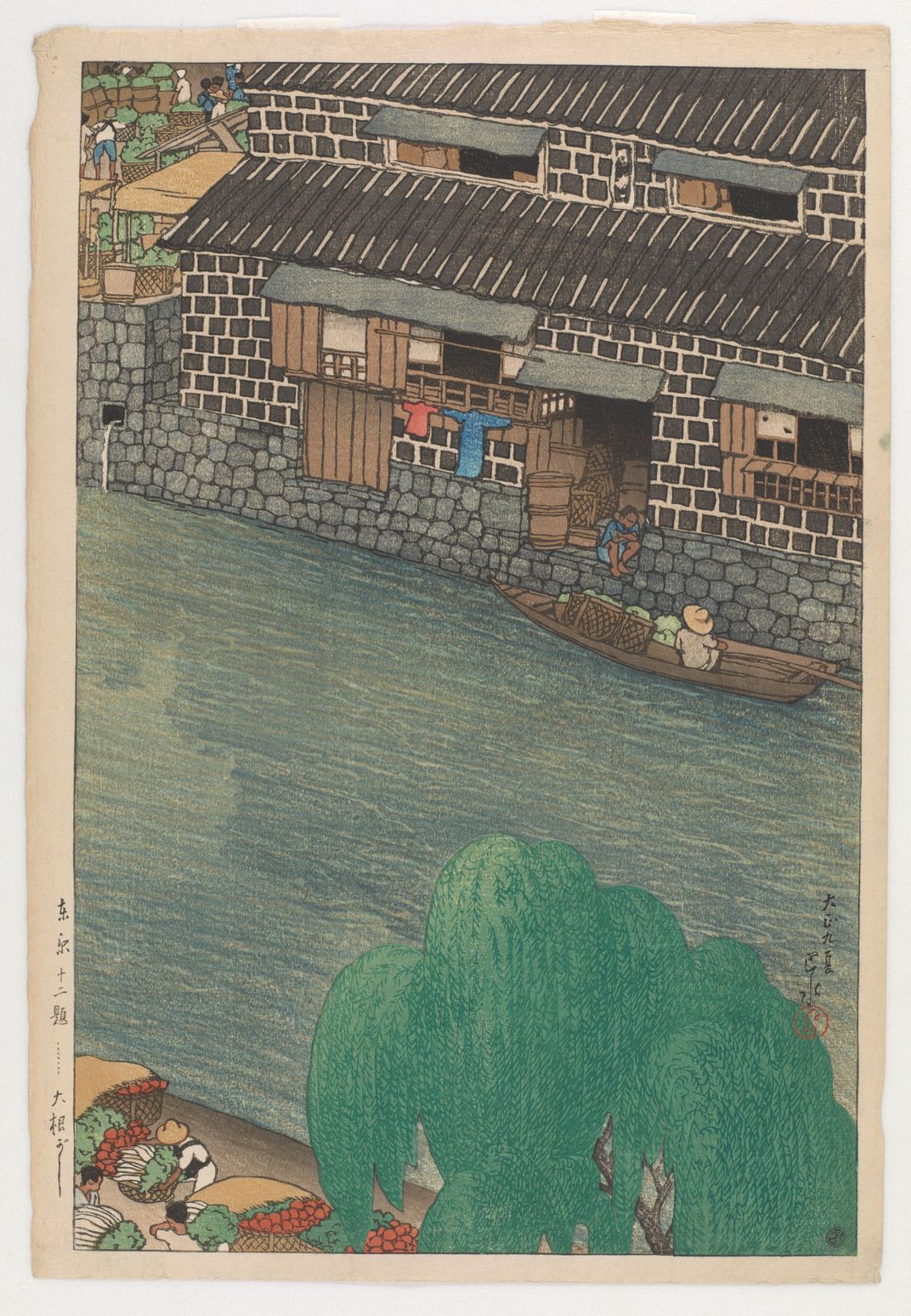

Pre-photography, that type of Tokyo mapping would have been done on a less grand scale through wood block printing. But printers struggled to prove their relevance in the face of photography’s rising popularity. As early as the 1870s, they began shifting how they worked. Shinbashi Railway Station, a bright, multicolored print done in 1873, was an example of the new style, showing off brick buildings and a train idling outside Yokohama station.

The proportions between the figures and buildings were accurate, and it has a photographic sense of perspective, says Feltens. But the gaudy colors were “emphatically unphotographic”—an attempt to compete with the medium that was then limited to black and white.

The effort, however, failed miserably—and printmaking fizzled out. In the 1920s, two new movements attempted to bring prints back to life. In the “new print” school, a publisher thought he could lure Westerners—who were snapping up idealized photographic views that presented a Japan that was perfectly modern and ancient simultaneously—with wood block prints that offered similar sentimental portraits.

Shin-Ohashi, from 1926, attempts this. It’s a night scene with the flicker of a gaslight reflected off the steel trestle of a railroad bridge; meanwhile, a man in a traditional straw hat pulls a rickshaw, while a kimono-clad woman holding a large parasol stands behind him. It was a naked bid to both outdo photography (pictures could not be taken at night) and to satisfy foreigners. “These kinds of prints were not sold to Japanese, even today,” says Feltens. They were also created as pieces of art to be collected—a new direction for prints.

In the 1930s, the “creative” movement began to take off. Japanese print makers had absorbed from Western art the idea that the creator’s genius was to be visible. Thus, printmakers began adding signatures—often in English—and edition numbers to their works. These were no longer the production of an army of carvers who handed their work off to a printing operation.

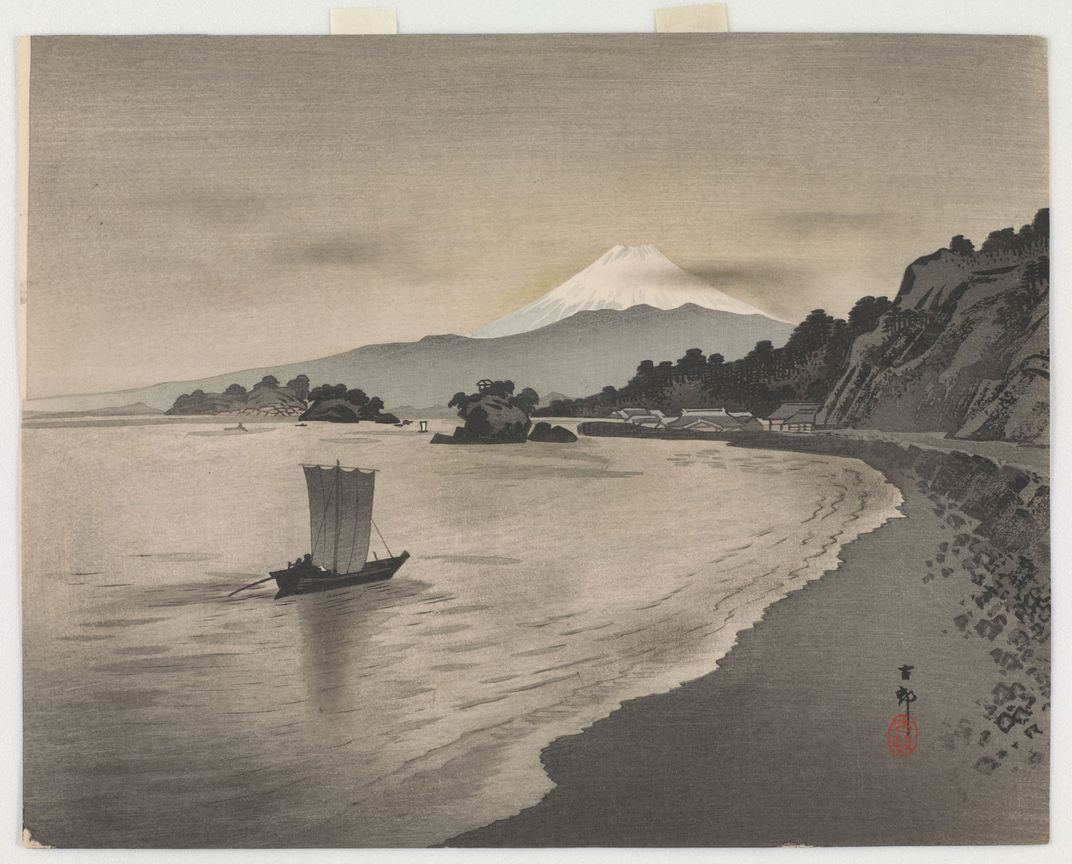

The printers were still using wood blocks, but in an increasingly sophisticated way. Color was a significant feature. And the perspective was still very photographic.

Ito Shinsui’s 1938 Mt. Fuji from Hakone Observatory is a masterpiece of photographic perspective and feel. The only tell are the range of blues, whites and browns.

Many of the 38 prints in the show are stunning in the depth of their artistry—a point that Feltens was hoping to make. “We wanted to show the breadth of color and shades, and this explosion of creativity happening,” especially from the 1930s onwards, he says. “These people, in terms of creativity, knew no limits,” says Feltens.

Like the photography show, the prints demonstrate that the artists had “an analytical gaze upon Japan,” Feltens says. But unlike the photographers, the print makers did not engage in direct or indirect political commentary or observations about World War II.

But there is a connection to that war, says Feltens. Many print collectors—including Ken Hitch, who loaned the Freer|Sackler a good number of the prints in the show—lived in Japan during the American occupation.

Both printmakers and photographers struggled to be accepted as fine arts in Japan, says Feltens. Ironically, prints, which were almost extinguished by photography, were the first to be recognized as a true art form, he says.

“Japan Modern: Photography from the Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck Collection,” curated by Carol Huh, and “Japan Modern: Prints in the Age of Photography,” curated by Frank Feltens, are both on view at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries in Washington, D.C. through January 24, 2019.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)