Archives of Groundbreaking Land Artist Nancy Holt Head to the Smithsonian

The papers illuminate the life of a woman whose career was often overshadowed by that of her husband, Robert Smithson

:focal(631x439:632x440)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b7/1d/b71dd5aa-dda9-45c1-aa48-91de7f923c32/leandrokatz-holt-001.jpg)

In the 1970s, land artist Nancy Holt erected a structure that sought to channel the overwhelming sunlight and heat of the Great Basin Desert in Utah into a single chamber. Aligning four concrete tubes measuring 18 feet in length and 9 feet in diameter into an “X” shape, Holt crafted an artwork that perfectly spotlights the sun during the summer and winter solstices.

Titled Sun Tunnels, the installation—which also projects constellations through holes on the sides of the massive cylinders—attempts to capture the enormity of the desert, coalesce the natural surroundings with human-made creation and underscore the circuitous nature of time: all aims of land art, which involves sculpting or designing structures that complement the natural landscape.

Last month, reports Gabriella Angeleti for the Art Newspaper, the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, announced a bequest of 50,000 items—including notes, design plans, project files, interviews and photographs—from Holt’s estate.

Upon the archives’ reopening, says interim director Liza Kirwin in an email to Smithsonian magazine, this vast collection will be accessible by “scholars, students, artists, collectors, and curators, for research projects, books, exhibitions, and films about Nancy Holt, her ideas and influence on contemporary art, as well as her art world network and the management” of her husband Robert Smithson’s estate. Staff hope to eventually digitize the papers.

Though she was one of the pioneering women of land art, Holt’s career has long been overshadowed by that of fellow land artist Smithson, who died in a plane crash in 1973 at age 35. Between Smithson’s untimely passing and her own death in 2014, writes Dale Berning Sawa for the Guardian, Holt “stewarded his archive—and ensured his enduring fame.” Now, the new bequest presents an opportunity to carve out a space in art history for Holt as a groundbreaking creator in her own right.

Land art, also known as earth art, gained traction in the 1960s and ’70s as a response to the commercialization of art. Participating artists explored modes of expression that emphasized ecological beauty: Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), for instance, draws on 6,000 tons of basalt rocks and earth to raise questions of entropy and ephemerality. Located in Utah’s Great Salt Lake, it ranks among the most widely recognized land art installations.

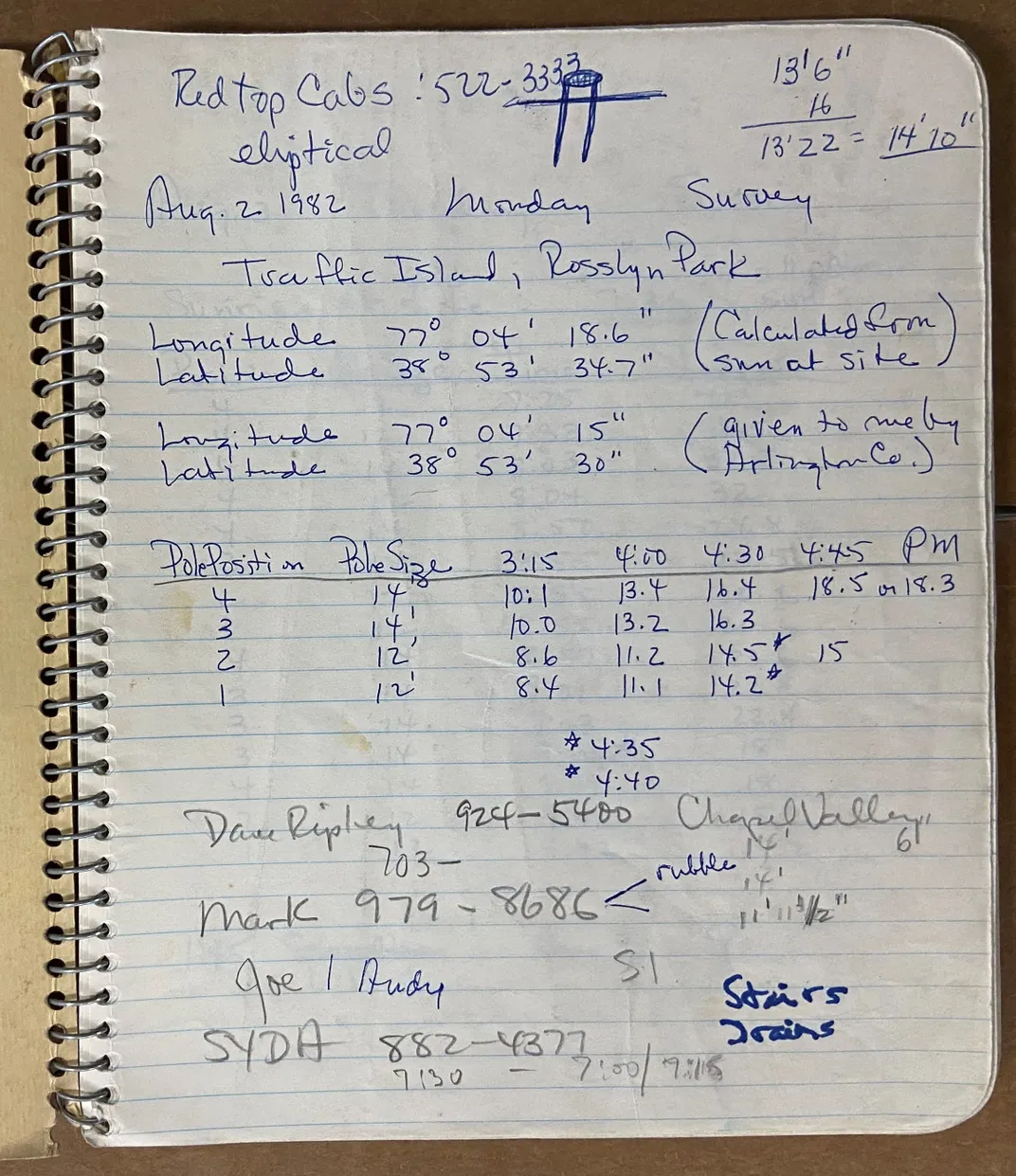

Together, Holt and Smithson contributed roughly 25 monumental earthworks and sculptures to the movement. Much like Sun Tunnels, Holt’s Dark Star Park in Arlington, Virginia, contains large sculpted spheres, a reflecting pool and metal poles that interact dynamically with the sun’s movement. Every year, at 9:32 a.m. on the morning of August 1, the shadows cast by the poles perfectly align with shadows on the ground.

“The alignment happens gradually and idiosyncratically,” says Angela A. Adams, director of Arlington Public Art, in a statement. “For a moment it looks like it’s not going to work and then all of a sudden, it snaps into place.”

From Sun Tunnels to Dark Star Park, Holt’s art elicits feelings of connectedness between the natural world and self. At the same time, her work challenges reductive interpretations of the landscape.

Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1938, Holt grew up in New Jersey before returning to her home state to study biology at Tufts University. She and Smithson wed in New York City in 1963, collaborating on a multitude of projects before his death in 1973. Holt relocated to Galisteo, New Mexico, where she lived for much of the rest of her life, in 1995. She often retraced the geography of her past by constructing artworks in places she’d once lived.

Per a Smithsonian statement, the renowned artist cultivated a long-term relationship with the Archives of American Art, donating eight separate gifts between 1986 and 2011. The couple’s papers are the archives’ third most-used collection, according to Kirwin. This most recent donation, she adds, will bolster the extant papers with sketchbooks, project files, letters, interview transcripts, press clippings and more ephemera that “provide a substantive record for Holt’s life and work.”

Holt’s oeuvre is expansive, says Kirwin: “Though she is known for her earthworks and commissioned public sculpture, the collection reveals the broad scope of her artistic production, including concrete poetry, audioworks, film, video, installations, earthworks, artists’ books, and public sculpture.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/9b/fd9b171d-4f53-458e-9ff9-497ca72e5598/2560px-robert_smithson_spiral_jetty_1970_20801602334.jpeg)

Through this bequest, visitors will be able to interact with the legacy of one of land art’s most prominent women practitioners.

“On a very basic level, simply by virtue of her gender Holt challenges the popular imagination of Land Art as an especially masculine arena,” says Gilbert and Ann Kinney New York Collector Jacob Proctor in an email to Smithsonian.

“Land Art has long had a reputation as a masculine arena populated by rugged men reshaping remote landscapes with heavy machinery,” he explains, adding that “although recent scholarship has complicated this reductive reading, it has proven remarkably persistent.”

As Randy Kennedy observed in Holt’s New York Times obituary, the artist was “underrecognized, in part because her best work … could not be shown in museums or galleries.” (The Holt/Smithson Foundation, which seeks to develop and preserve the couple’s creative legacies, holds her artworks separately from the papers now in the Smithsonian’s collections.)

Holt, for her part, firmly believed that land art was experiential—meaning it needed to be appreciated in person and at the right time.

“Words and photographs of the work are memory traces, not art,” she once said. “At best, they are inducements for people to go and see the actual work.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/graciephoto.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/graciephoto.jpg)