The Unsung Inspiration Behind the “Real” Rosie the Riveter

Historians pay tribute to the legacy of Naomi Parker Fraley, who died Saturday at 96. In 2015, she was linked, circumstantially, to the We Can Do It poster

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/8e/b38e361c-3749-4087-bcb3-db38e7d5b3a3/nmah-87-13107.jpg)

In 1942, something strange—and mildly scandalous—happened at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, California: due to safety concerns, the base commander instructed all women employees working with machinery to wear pantsuits.

At the time, pants-clad women were such an unusual sight that a photojournalist from the Acme photo agency was sent to document the scene. While taking photos at the base, the photographer snapped a picture of 20-year-old Naomi Parker Fraley, who, like many women in the 1940s, had taken an industrial job to help with the war effort. In the resulting black-and-white image, which was published widely in the spring and summer of 1942, Fraley leans intently over a metalworking lathe used to produce duplicate parts. Her blouse is crisp, her hair secured safely in a polka-dot bandana.

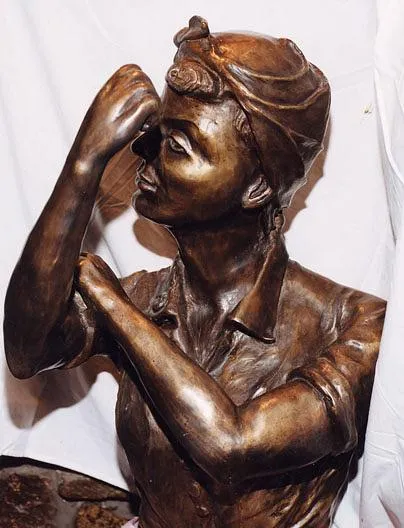

Fraley, who died on Saturday at the age of 96, stayed out of the spotlight for most of her long life. But several years before her death, a scholar put forth a compelling case arguing that the photo of Fraley at the Naval Air Station had inspired one of the most iconic images to emerge from the World War II era: the vibrant “We Can Do It” poster, which features a defiant Rosie the Riveter with her bicep curled and her hair wrapped up in a polka-dot bandana—not unlike the one that Fraley wore on the job. Fraley, in other words, might very well have been the real Rosie the Riveter.

If Fraley lived much of her life in obscurity it is, in part, because nobody was looking for her. Though the “We Can Do It” poster has in recent years become a ubiquitous feminist symbol, it was first created as a wartime poster for the Westinghouse Electric Corporation’s plants. William L. Bird, a curator at the National Museum of American History and co-author of the book Design for Victory, tells Smithsonian.com that industrial companies frequently ran poster campaigns with various instructions for new women employees: return your tools at the end of the day, don’t take too many breaks, keep the workplace clean, and so on.

“These were basically a way that factory managers were able to routinize their labor force, [so that the] many women who had not had factory jobs before because they weren't available would be acquainted with how we do things here,” Bird explains.

The “We Can Do It” poster was drawn by Pittsburgh-based artist J. Howard Miller, who created a series of images for Westinghouse. One illustration that has not stood the test of time, for instance, featured a bespectacled man holding rolled up blueprints, with a caption that reads: “Any Questions about your work? Ask you supervisor." The “We Can Do It” poster, with its electric-yellow background and robust Rosie, is considerably more arresting. But Bird points out, its intent didn’t “have much to do with empowering people in terms of anything other [than] to complete assignments on time.”

Miller’s poster was circulated in Westinghouse factories during the war and subsequently disappeared. But in the 1980s, the National Archives in Washington featured a copy of the “We Can Do It” poster in one of its exhibits and, according to Bird, “began to merchandise that image on all manner of paraphernalia in their shop.” After seeing the National Archives exhibit, Bird acquired an original “We Can Do It” poster from Miller for the Smithsonian. And Miller’s industrial illustration was soon adopted as a symbol of aspiration and resilience for women.

Many years would pass before Fraley’s name surfaced in connection to the iconic image. Instead, Miller’s Rosie was believed to have been based on a woman named Geraldine Hoff Doyle, who had worked as a metal presser in a Michigan plant during the war.

In 1984, Doyle was thumbing through Maturity Magazine when she came across the 1942 photo of a young woman standing over an industrial lathe. Doyle thought she recognized herself in the image. Ten years later, Doyle saw an issue of Smithsonian Magazine that featured the “We Can Do It” poster on its cover, and was convinced that this illustration was based on the photo of her at work in a wartime factory. Soon, it was being widely reported that Doyle had been the inspiration for Miller’s Rosie.

But James J. Kimble, an associate professor at New Jersey’s Seton Hall University, wasn’t so sure. When Doyle died in 2010, and a stream of obituaries touted her as the real Rosie the Riveter, Kimble saw an opportunity to try and “find out how we really know it was Geraldine,” he tells Smithsonian.com. “And if it wasn't, who was it?”

Kimble poured through books, magazines and the internet, hoping to find a captioned version of the 1942 photograph. And finally, he located a copy of the image at a vintage photo dealer. As Joel Gunter of the BBC reports, the picture was captioned with a date—March 24, 1942—the place where it was taken—Alameda, California—and, much to Kimble’s excitement, an identifying caption.

“Pretty Naomi Parker looks like she might catch her nose in the turret lathe she is operating,” the text reads.

Assuming that Fraley had died, Kimble enlisted the help of a genealogical society to track down her descendants. “They sent me a letter after two or three months of doing their own sleuthing,” Kimble recalls, “and the letter said something like, ‘Jim we have to stop working on this case because … we can't provide information on people who are still alive. We have every reason to believe she is.’ Just imagine that moment where everything is turned on its head and I realize this woman may actually be out there somewhere.”

In 2015, Kimble visited Fraley, who was living with her sister, Ada Wyn Parker Loy, in a remote, wooded area of Redding, California. After the war, according to Margalit Fox of the New York Times, Fraley worked as a waitress at the Doll House, a popular California establishment, got married and had a family. For decades, she kept a clipping of the wire photo that had been taken of her as a young woman at the Naval Air Station in Alameda.

Kimble says that when he showed up on Fraley’s doorstep, she greeted him with a “huge sense of relief.” In 2011, Fraley and her sister had attended a reunion of women wartime workers at the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California. For the first time, Fraley saw the “We Can Do It” poster displayed alongside the 1942 wire photo—which identified its subject as Geraldine Hoff Doyle. Fraley tried to alert National Parks Service officials to the error, but was unable to convince them to change the attribution.

After Kimble went public with the results of his research, Matthew Hansen of the Omaha World Herald contacted Fraley for an interview. Because Fraley was very hard of hearing during the last years of her life, they spoke over the phone with Ada’s help. Hansen asked how it felt to be known as Rosie the Riveter. “Victory!” Fraley could be heard yelling in the background. “Victory! Victory!”

Admittedly, the evidence connecting the photo of Fraley to the “We Can Do It” poster is circumstantial—J. Howard Miller never revealed the inspiration for his now-famous illustration. But, Kimble says, it is entirely plausible that Miller’s Rosie was based on Fraley. “They look like each other,” he explains. “There's the polka dot ... bandana. The timing is right. We know [the 1942 photo] appeared in the Pittsburgh press, which is where Miller lived … It's a good guess.”

Throughout his six-year quest to uncover the true history of the “We Can Do It” poster, Kimble was propelled forward by the desire to correct a historical error—an error that omitted the important role one woman made to the war effort. “At a certain point in time, [for] three or four years, Naomi Parker Fraley is disempowered,” Kimble explains. “Her identity has been taken away from her—innocently, but nonetheless she feels disempowered … So it was important, I think, to correct the record for that reason alone.”

He takes comfort that Miller’s poster—or at least what Miller’s poster has come to stand for in the decades after the war—has gone on to transcend the identity of a single person.

“I think our culture ought to value what those women did: those Rosies, those riveters, and those many women who are not named Rosie and who didn't rivet and nonetheless contributed to the war effort,” he says. “Naomi is important because she is one of them.”