NASA Radar Detects Abandoned Site of Secret Cold War Project in Greenland—a ‘City Under the Ice’

Camp Century was built in 1959 and advertised as a U.S. research site—but it also hosted a clandestine missile facility

:focal(652x874:653x875)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/ea/e9eaf163-f961-4b15-9c75-c953cd78d680/campcentury_aerial_radar_lrg.jpg)

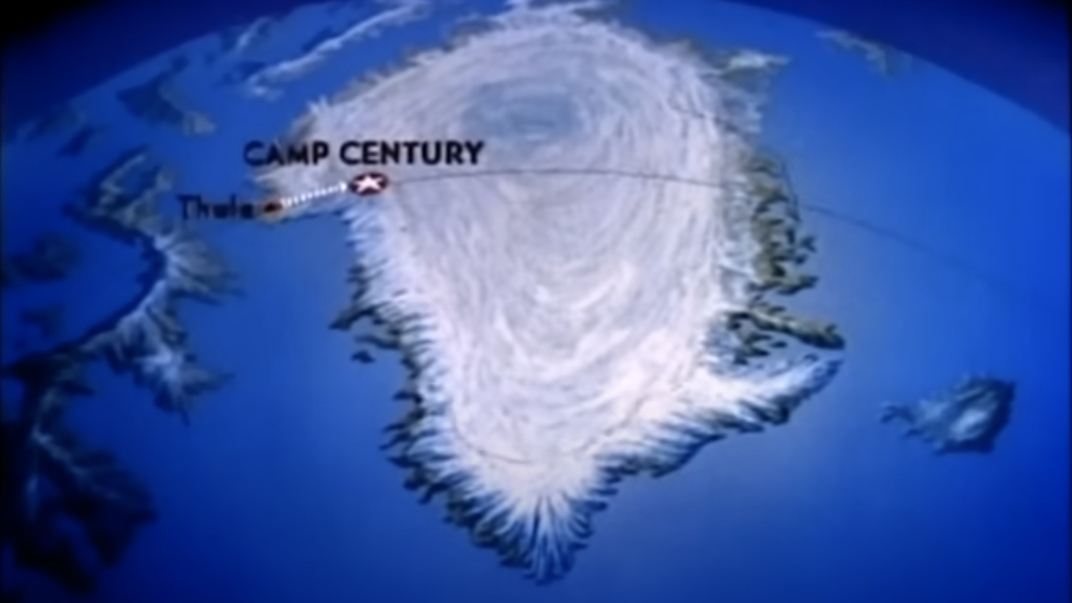

In April, a team of scientists and engineers flew a jet above northern Greenland to test the capabilities of a radar instrument. About 150 miles east of Pituffik Space Base, Chad Greene, a NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory scientist, snapped a photo of the white expanse below them. At the same time, the radar detected something surprising under the ice: an abandoned Cold War-era base.

“We were looking for the bed of the ice and out pops Camp Century,” Alex Gardner, a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who helped lead the project, says in a statement. “We didn’t know what it was at first.”

Dubbed the “city under the ice,” Camp Century was a military base built into the Greenland ice sheet by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1959. At the time, it was near the surface layer—now, after snow and ice accumulated over the decades, it’s buried at least 100 feet deep. Back then, Camp Century was advertised as a polar research site, per Popular Science’s Andrew Paul. Its scientists did collect the world’s first ice core samples, which are still referenced in research today, but the facilities also hosted a much darker venture: a top-secret Cold War mission called Project Iceworm.

The classified effort aimed to house and launch a system of missiles within a network of tunnels beneath the ice. The weapons, a type of nuclear missile known as “Iceman,” could launch through the ice sheet, per Space.com’s Brett Tingley. Their potential target was the Soviet Union.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/27/42/2742b94d-afe5-496b-b03d-b4034df81548/camp_century_drill-crrel.jpg)

A Popular Science issue from February 1960 described the project for readers: “In building the fantastic community, 800 miles from the North Pole, Army Engineers, in cooperation with the Danish Government (Greenland is a part of the Kingdom of Denmark), have proved that the traditionally antagonistic Arctic can be tamed… It will be home—snug, comfortable and warm—for 100 scientists, engineers and soldiers who are expected to move in late this year,” as reported by Popular Science. However, the U.S. army didn’t immediately share Project Iceworm’s true nature with the Danish government.

The construction of Camp Century in such a remote location—where temperatures can drop to minus 70 degrees Fahrenheit and wind speeds can be stronger than 120 miles per hour—is certainly impressive. And the facility was one of the first to draw power from a portable nuclear reactor, per Newsweek’s Jess Thomson, which was removed in 1967, when the camp and Project Iceworm were abandoned because of the impracticality of maintaining the structure within the constantly moving ice sheet.

Tons of hazardous waste, however, were left behind, including 53,000 gallons of diesel fuel, 63,000 gallons of wastewater (including sewage) as well as unknown amounts of low-level radioactive coolant from the reactor, according to estimates by the University of Colorado Boulder’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES).

A study published in 2016 also suggests the site might contain toxic pollutants such as polychlorinated biphenyls. Now, scientists are concerned that Earth’s rising temperatures might melt the ice covering Camp Century and expose the waste.

“When we looked at the climate simulations, they suggested that rather than perpetual snowfall, it seems that as early as 2090, the site could transition from net snowfall to net melt,” William Colgan, a climate and glacier scientist at York University and co-author of the 2016 study, said in a statement at the time. “Once the site transitions from net snowfall to net melt, it’s only a matter of time before the wastes melt out; it becomes irreversible.”

Camp Century has been detected by previous airborne surveys, but those radars have produced two-dimensional maps without much detail, per the statement. When spotted by the team in April, however, NASA’s UAVSAR (Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar), mounted on the belly of the plane, provided a map with more dimensionality than previous data, and the results seem to align with historical documentation of the site.

“In the new data, individual structures in the secret city are visible in a way that they’ve never been seen before,” Greene explains in the statement.

Scientists expect to use the UAVSAR to measure ice sheet thickness in Antarctica and refine estimates of future sea-level rise. The usefulness of the UAVSAR’s image of Camp Century is still unclear, but the unexpected detection was certainly a blast from the past.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Margherita_Bassi.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Margherita_Bassi.png)