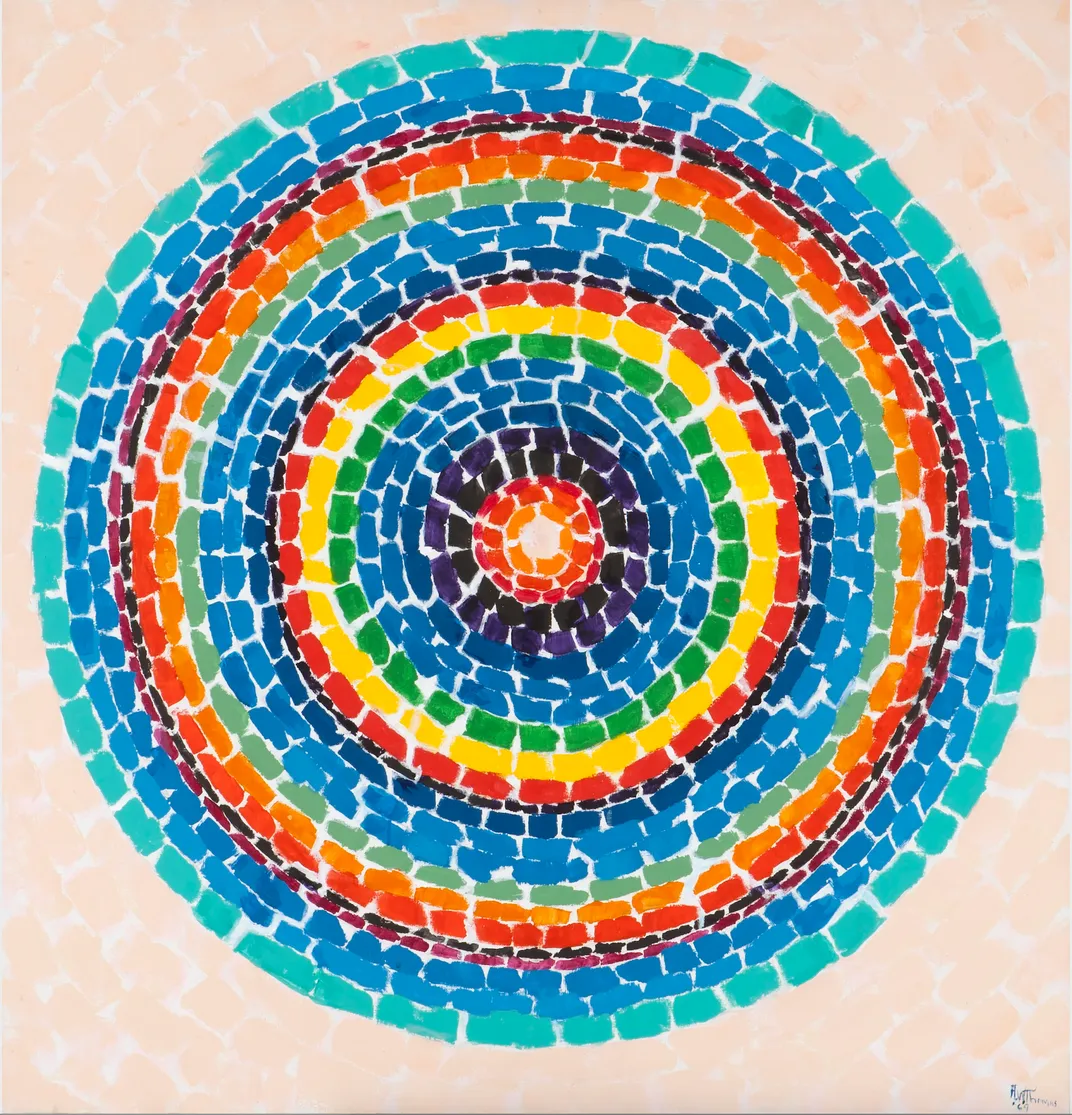

The late African American artist Alma Thomas created the painting Air View of a Spring Nursery—a fragmented gradient of bright colors—in 1966. Looking at the rainbow-hued artwork evokes images of a spring day brimming with flowers like poppies, peonies and pansies. As the painter once said, she was inspired by “the leaves and flowers tossing in the winds as though they were dancing and singing.”

This abstract scene is one of dozens of Thomas works now on view at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia. Per a statement, “Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful” explores “multiple themes from Thomas’ life and career,” demonstrating how her “artistic practices extended to every facet of her life, from community service and teaching to gardening and dress.”

Beginning this fall, the exhibition will travel to the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C.; the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, Tennessee; and the Columbus Museum in Columbus, Georgia. Curators organized the show in collaboration with the Columbus, which is located in the artist’s birthplace.

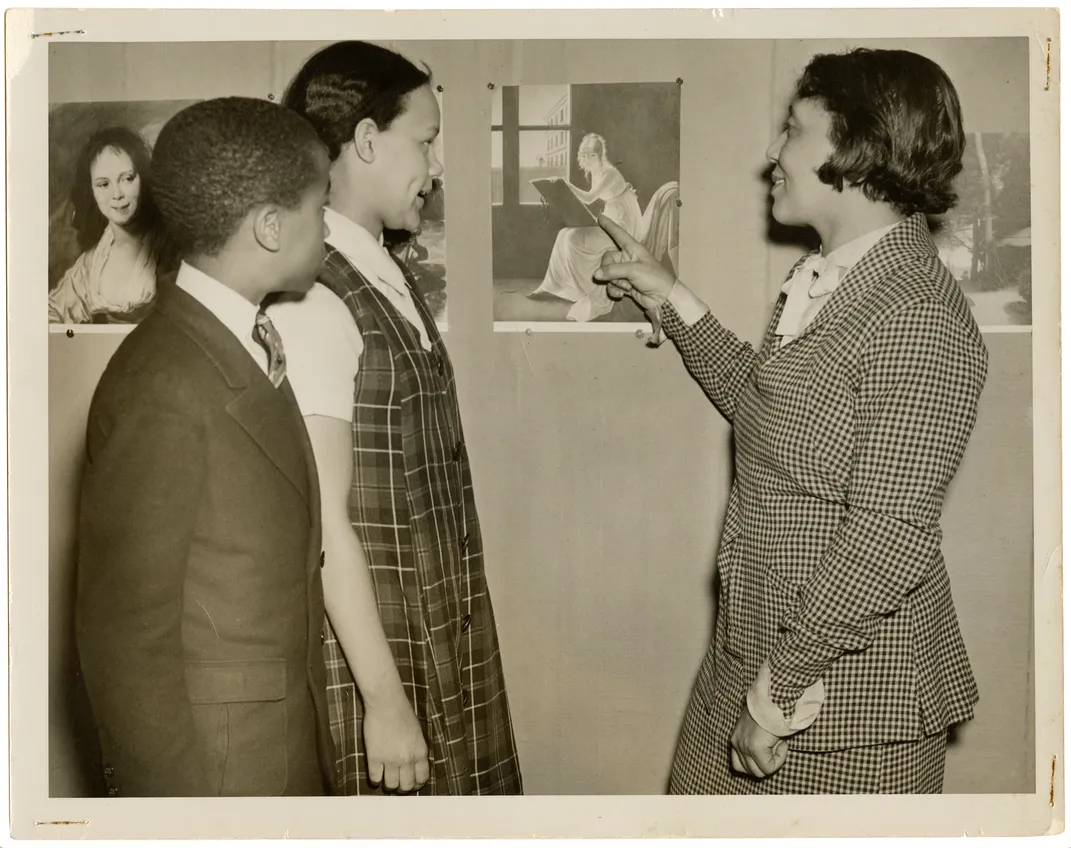

“One of the goals of the show has been to have a Columbus-originated story,” curator Jonathan Frederick Walz tells Artnet News’ Sarah Cascone. “There seems to be this received wisdom that Thomas only became an artist after she stopped teaching in the classroom in 1960, but the material that we had at the museum made us realize that, in fact, she had been making art all along.”

According to the Virginian-Pilot’s Saleen Martin, the retrospective includes some 150 abstract works, seldom-seen costume designs and sculptures that speak to Thomas’ creative process. The survey also features student work from the 1920s and marionettes from the ’30s, as well as personal artifacts like a patterned orange-and-white dress often worn by the artist.

One highlight of the exhibition is Horizon (1974), an acrylic on paper outfitted with mustard yellow, bright red, aqua blue and navy stripes. This piece, like many of Thomas’ others, shows a field of color coming together to form a complete picture.

“Visitors are just going to come in and they're going to be bedazzled, because if you're not familiar with her work, they're eye-poppingly beautiful, they're so colorful and so bright,” Seth Feman, deputy for art and interpretation at the Chrysler, tells Julio Avila of WTKR. “They evoke a kind of cheer which really is at the core of who this artist was. She was full of life and love, and you see it in the paintings.”

Born in Columbus, Georgia, in 1891, Thomas was the eldest of four siblings. Per the Smithsonian American Art Museum, her father was a businessman, and her mother was a seamstress. The family led a pleasant life, residing in a spacious Victorian home atop a hill overlooking Columbus. In 1907, at the age of 15, Thomas and her family moved to Washington, D.C., where the artist remained for the rest of her life.

In 1921, the young painter enrolled at Howard University as a home economics student. But she quickly found herself attracted to the arts, eventually becoming the first graduate of the school’s newly established fine art department.

As an adult, Thomas made dynamic, brightly colored abstract works that often featured circular shapes. According to Peter Schjeldahl of the New Yorker, her artistic influences included Wassily Kandinsky and Henri Matisse, whose works she saw in a 1961 show of his paper collages at the Museum of Modern Art.

Many of Thomas’ abstract works drew on plants and color palettes inspired by flower beds. These colorful canvases resonated with viewers, and in the 1970s, Thomas became the first Black woman to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

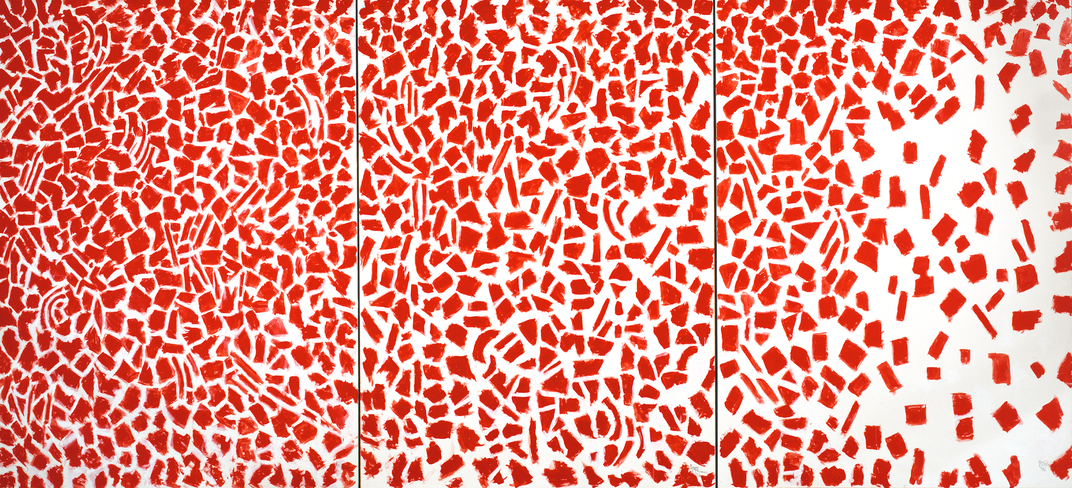

Some of the non-representational works in the Chrysler show, such as Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music (1976), reference natural phenomena, like a sheet of falling rose petals. Per the Pilot, the six-foot-tall painting is the largest known work by the artist, who created the piece when she was 80 years old and suffering from arthritis.

“You can see in the brushstrokes themselves, the way that she is adapting,” Feman tells the Pilot. “The difficulty that she’s having holding brushes; she’s not just trying to work around it. She’s making use of it.”

In addition to creating abstract artworks, Thomas contemplated political themes, making sketches and paintings of scenes like the 1963 March on Washington. Thomas and her peers also protested museums and galleries that didn’t represent artists of color.

“Her late abstractions kind of end up standing for her entire career,” Walz tells Artnet News. “Our project with this show is to show that Thomas was multifaceted.”

Thomas continued creating art until her death in 1978 at age 86.

Following her lifetime, Thomas fell into relative obscurity. But her work began to rise in popularity again in 2009, when the Obama family hung Sky Light (1973) in their private residence at the White House. Now, Thomas’ paintings appear regularly in prominent museum shows, such as the Brooklyn Museum’s 2019 exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” and a 2016 solo exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

“Through color,” said Thomas in 1970, “I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.”

“Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful” is on view at the Chrysler Museum of Art through October 3.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ce/28/ce28b90c-8842-4a74-af3a-64e54a18fbc0/mobile_alma.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fd/ad/fdad3813-5449-4393-ad5f-578672326100/social_alma.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Isis_Davis-Marks_thumbnail.png)