New Book Chronicles the Lives of Jack the Ripper’s Victims

Contrary to popular belief, the five women were not all prostitutes, but rather individuals down on their luck

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8f/17/8f17c5b6-cd89-4b43-973c-89e50b045327/jack_the_ripper_victims.jpg)

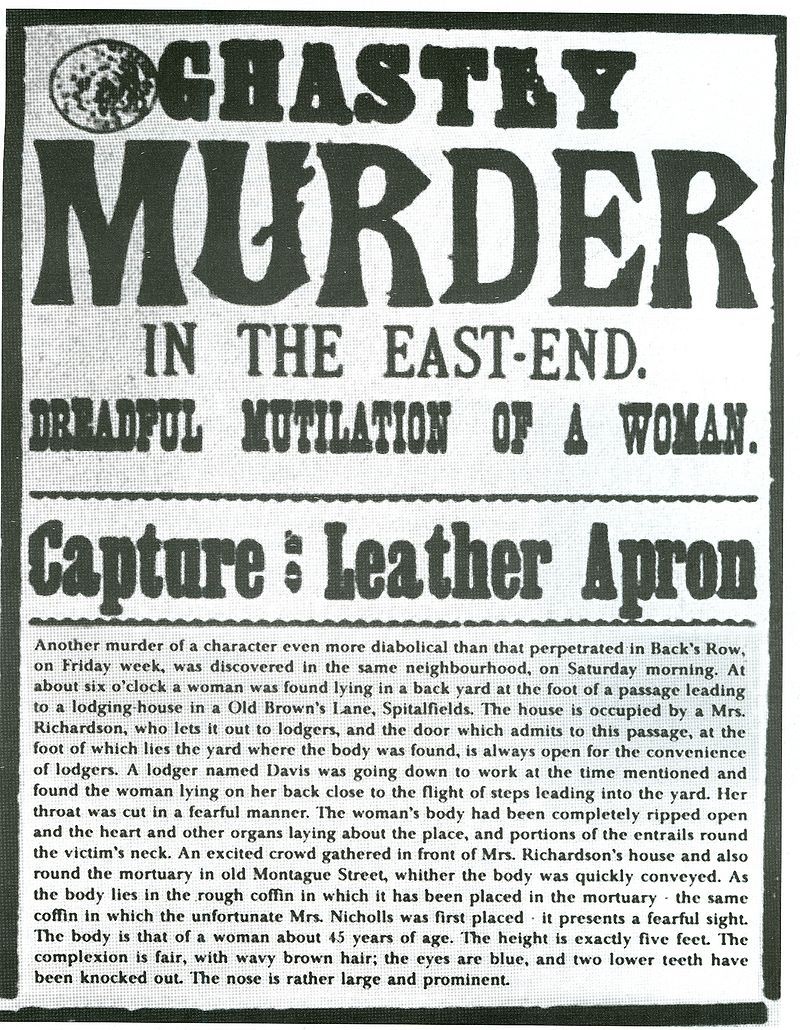

All too often, murder victims’ stories are relegated to the footnotes of history, overshadowed by not only their violent ends, but the looming specter of their killers. In The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, historian Hallie Rubenhold sets out to correct this imbalance, placing the focus on Polly Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly—an eclectic group whose ranks include a fraudster, a traveling chapbook seller and a spurned wife who entered the workhouse after discovering her husband’s infidelity—rather than the still-unidentified serial killer who ended their lives in 1888.

“We always start with the murders, then focus on who Jack the Ripper was, to the point that he has become a supernatural creature,” Rubenhold explains in an interview with the Guardian’s Sian Cain. “... But he was a real person, who killed real people. This all happened. And our disassociation from the reality is what dehumanised these women. They have just become corpses.”

Perhaps the most significant takeaway of the new research is Rubenhold’s debunking of a popular myth surrounding the so-called “canonical five”: As Maya Crockett points out for Stylist, Jack the Ripper’s victims are often identified as prostitutes, but in actuality, there is no evidence tying Nichols, Chapman and Eddowes to the profession.

Kelly was the only one making a living as a sex worker at the time of the murders, according to a Penguin Random House blog post. Stride, despite finding herself entangled in a state-run prostitution ring back in her home country of Sweden, pursued alternative paths—including running a coffeehouse and, upon that venture’s failure, masquerading as a shipping disaster victim in order to defraud the well-to-do—upon immigrating to England.

What united these five females, in the words of the Times’ Daisy Goodwin, was not their occupation, but the fact that during the twilight of the Victorian era, “it was all too easy for women to end up sleeping on the streets.” Indeed, Frances Wilson writes for the Guardian, the five’s lives traced the same broad strokes: Born into poverty or reduced to it later in life, the women endured faithless and abusive husbands, endless cycles of childbearing and childrearing, and alcohol addiction. Sooner or later, they all ended up homeless, spending their nights in the winding alleys of London’s Whitechapel district.

The Ripper’s first victim, Nichols, was murdered at age 43. According to Stylist’s Crockett, she was a blacksmith’s daughter who grew up in the fittingly titled Gunpowder Alley, a neighborhood known for inspiring the sleazy character Fagin’s lodgings in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist. In 1876, Goodwin notes for the Times, Nichols, her husband and their three children moved into tenements built by philanthropist George Peabody to house the “deserving poor.” Unlike most cheap accommodation at the time, the apartment buildings boasted indoor lavatories and gas-heated water.

But within a few short years, Nichols, disgusted by her husband’s philandering, left the relative comfort of home for a workhouse, which Londonist describes as a seedy institution where society’s poorest labored in exchange for food and shelter. After a subsequent spell as a maid, Nichols landed on the streets, where she soon encountered the Whitechapel killer.

Unsurprisingly, the Guardian’s Wilson reports, an inquest into Nichols’ death revealed investigators’ attempts to blame her murder on the transient lifestyle she was leading. As a coroner reportedly asked her former roommate, “Do you consider that she was very cleanly in her habits?” (In other words, Wilson translates, “Was Nichols a prostitute and thus deserving of her fate?”)

Chapman, the Ripper’s second victim, might have led a middle-class life had she not suffered from alcoholism. The wife of a gentleman’s coachman, she had eight children, six of whom, according to the Guardian’s Cain, were born with health issues stemming from their mother’s addiction. At one point, Helena Horton writes for the Telegraph, Chapman visited a rehabilitation center in search of treatment but was unable to make a full recovery. Alcoholism enacted a heavy toll on her marriage, and by the end of Chapman’s life, she, like Nichols, was sleeping on the streets of Whitechapel, a “fallen woman,” in Rubenhold’s words, destroyed not by sexual transgressions but the equally unenviable label of “female drunkard.”

Stride and Eddowes—victims three and four—were murdered within hours of each other the night of September 30, 1888. Stylist’s Crockett suggests that by the end of her life, Stride, the sex worker-turned-maid, coffeehouse proprietor and finally fraudster, may have been experiencing debilitating mental health issues linked with syphilis.

Eddowes, comparatively, came from a more advantageous background: Thanks to a primary school education, she was fully literate and, as the Guardian’s Wilson notes, able to transcribe ballads penned by her common-law partner, Thomas Conway. The couple roamed England, selling poetry pamphlets known as chapbooks, but after Conway became abusive, the two split up. Astonishingly, some 500 friends and family members turned up for Eddowes’ funeral.

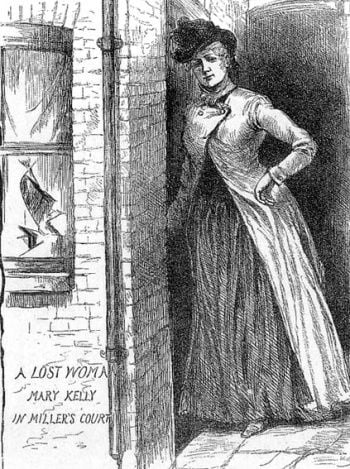

Kelly, the Ripper’s last victim, was the only one of the five to be labeled “prostitute” on her death certificate. While all of the others were in their 40s at the time of the murders, she was just 25 years old. Given her age and profession, there is little reliable information regarding her life. But as Cain writes, Rubenhold’s research has led her to believe Kelly narrowly escaped sex traffickers during a trip to Paris. Upon returning to London, she moved between brothels and boarding houses; of the Ripper’s victims, she was the only one murdered in a bed rather than on the streets.

Significantly, Goodwin observes for the Times, Rubenhold dedicates little space to the man who killed her subjects and the gory manner in which he did so. Beyond positing that the women were asleep when murdered, making them easy targets for a prowling predator, The Five emphasizes the victims’ lives, not their deaths.

“At its very core, the story of Jack the Ripper is a narrative of a killer’s deep, abiding hatred of women, and our cultural obsession with the mythology only serves to normalise its particular brand of misogyny,” Rubenhold writes. “It is only by bringing these women back to life that we can silence the Ripper and what he represents.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)