Now We Don’t Have to Unravel Mummies to Study Them at a Cellular Level

Phase-contrast imaging enabled researchers to non-invasively examine a mummified hand’s blood vessels, skin layers and connective tissue

:focal(396x323:397x324)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/c8/9bc8e599-3919-4d19-b418-32fd5cc1a0e0/hands2myself.png)

During the 19th century, the looting of ancient Egyptian treasures was manifest. Swedish nobleman Carlo Lundberg was one of the many who simply took artifacts of interest back home. For Lunderg, that included a mummified hand dating to around 400 B.C. Although the hand was in relatively good condition, researchers had no way to examine the well-preserved soft tissue without physically removing it from its linen wrappings. So, for the next 200 years, its tissue remained unstudied.

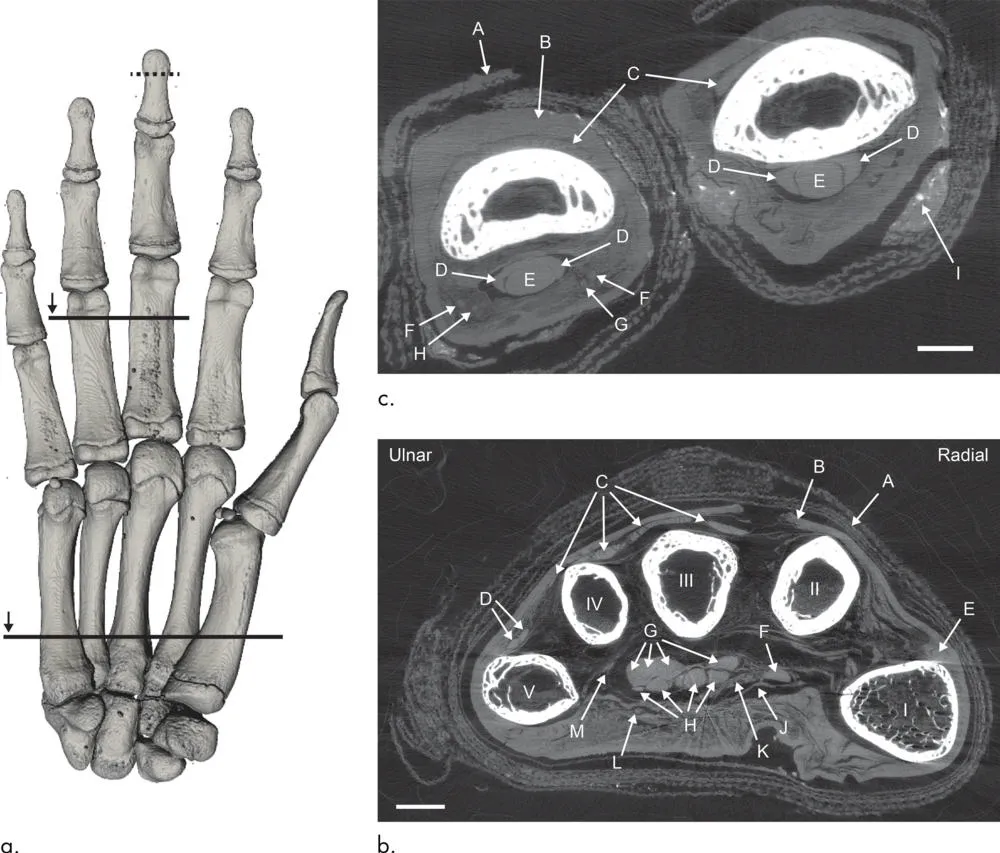

Now, Kiona N. Smith reports for Ars Technica, researchers led by Jenny Romell, a physicist at Stockholm’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology, have used a variation of CT scanning known as propagation-based phase-contrast imaging to bypass the mummified hand’s wrappings and produce high-resolution scans of its one-time owner’s blood vessels, skin layers and connective tissue—all without inflicting damage to the ancient remains.

The team’s innovative use of CT scanning was recently detailed in Radiology. As George Dvorsky notes for Gizmodo, scientists have long relied on conventional CT scanning and similarly non-invasive imaging techniques to peer beneath mummies’ wrappings, but they’ve never been able to view mummified soft tissue at such a microscopic, detail-rich level, as most forms of soft tissue don’t produce the level of contrast necessary to produce high-resolution X-ray scans. If archaeologists and researchers wanted to examine mummified tissue, they were forced to extract physical samples and analyze them with a microscope.

Comparatively, propagation-based phase-contrast imaging (as its name suggests) utilizes not just the absorption of X-ray beams into a sample, but the change that occurs when the beam phases through it. As Cosmos’ Andrew Masterson explains, the combined approach creates a higher contrast, resulting in a higher-resolution image of soft tissue.

That’s why phase-contrast imaging is already used to examine the soft tissue found in living humans. But Romell and her team wanted to test the technology’s research applications, which brings us back to that 2,400-year-old mummified hand, which is held in the collections of Sweden’s Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities. Their scans of both the specimen in its entirety and the tip of the middle finger, zooming in at resolution of between 6 and 9 micrometers—slightly larger than the width of a human red blood cell—successfully captured the mummified hand’s fat cells, blood vessels and nerves.

Romell tells Smith of Ars Technica that she and her team don’t plan on conducting additional mummy experiments in the immediate future, but they hope their research provides a new avenue of exploration for medical researchers, archaeologists and researchers working in the field of paleopathology, or the study of ancient disease.

"There is a risk of missing traces of diseases only preserved within the soft tissue if only absorption-contrast imaging is used," Romell said in a Radiological Society of North America statement. "With phase-contrast imaging, however, the soft tissue structures can be imaged down to cellular resolution, which opens up the opportunity for detailed analysis of the soft tissues."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)