New Exhibit Highlights the Art of the Courtroom Sketch

For decades, these drawings offered the public its only glimpse into high-profile court cases

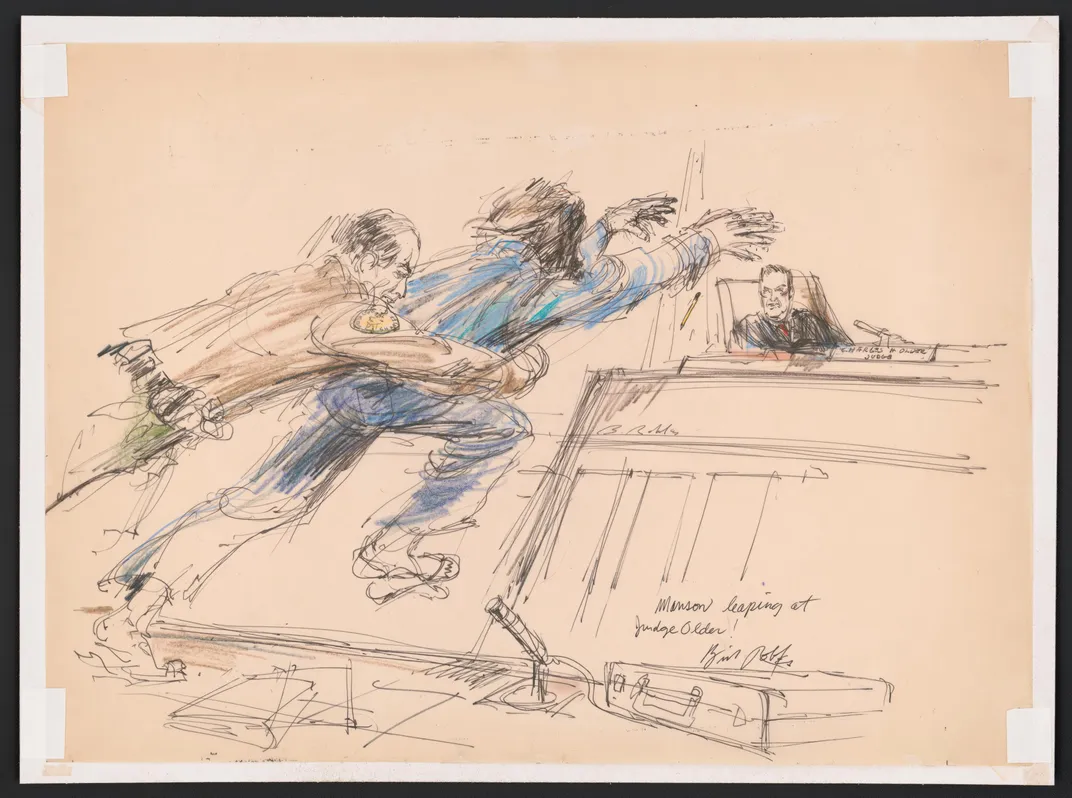

It was one of the most dramatic moments in American courtroom history. During his 1970 trial, serial killer Charles Manson leapt up from his seat and tried to stab the presiding judge with a pencil. Cameras were not allowed into the trial, but the frenetic scene—the pencil flying out of Manson’s hand as he was tackled by a bailiff, the judge looking on, entirely nonplussed—was captured by courtroom artist Bill Robes. His sketch, swirling with activity, opened Walter Cronkite’s CBS News broadcast that night.

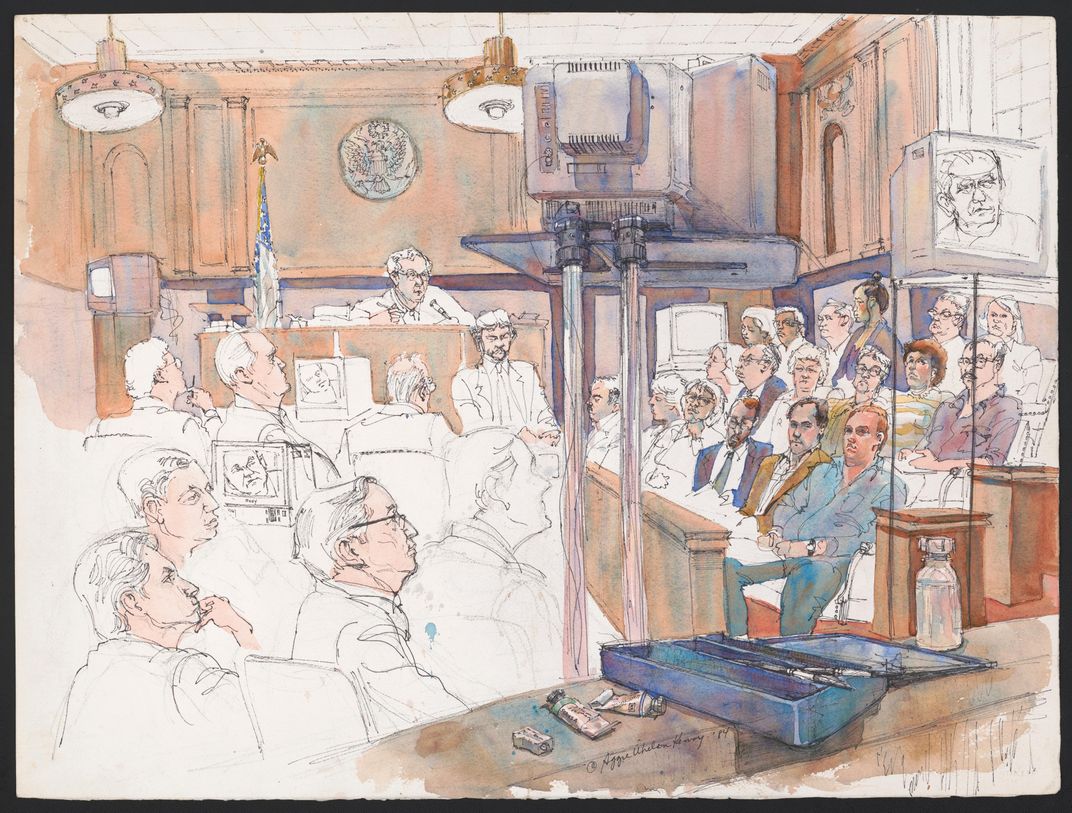

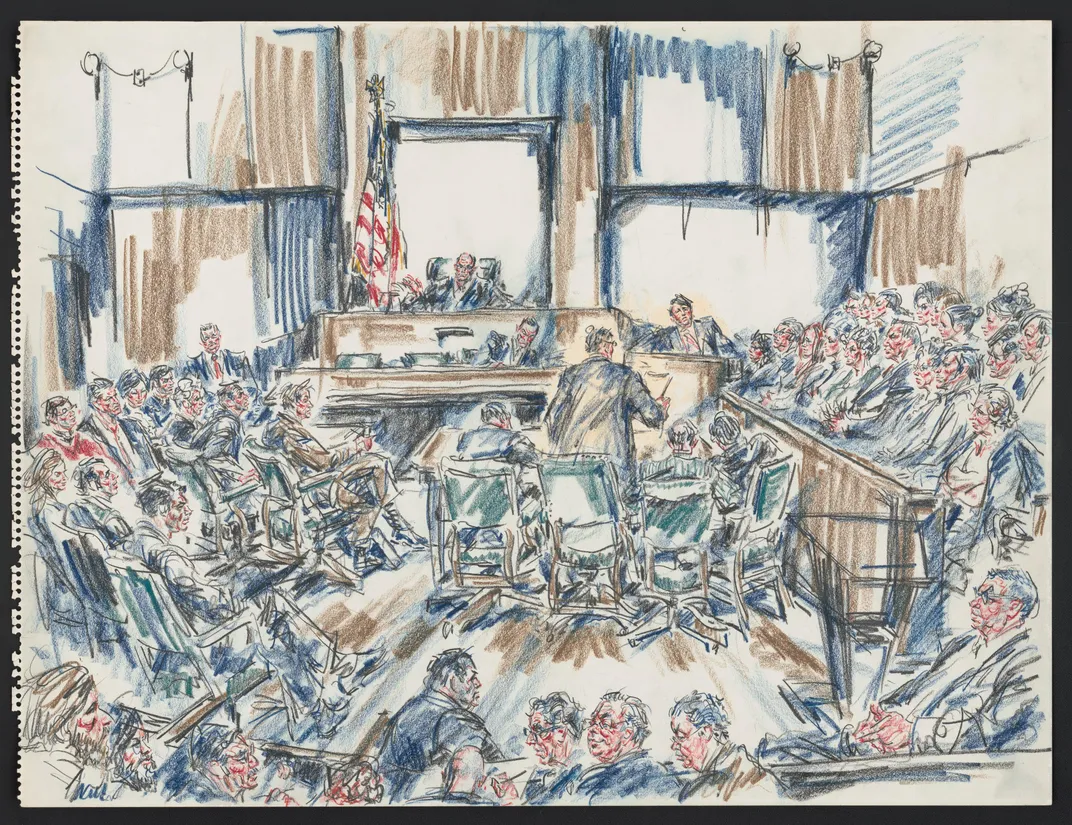

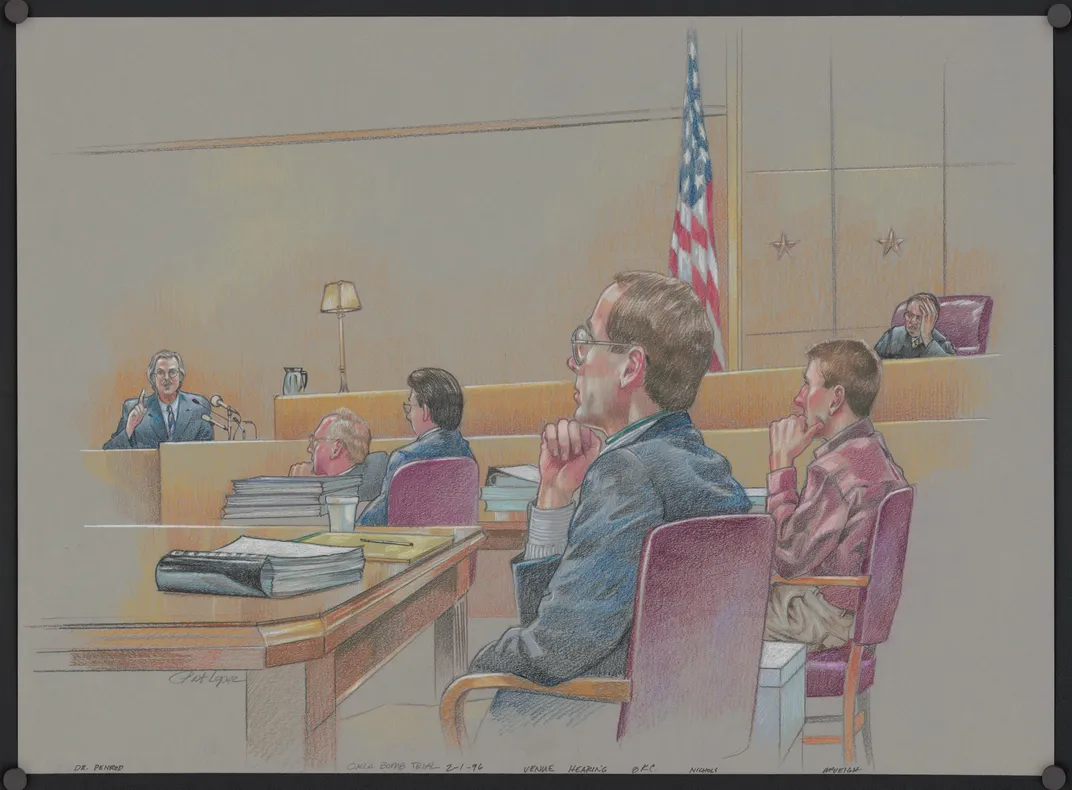

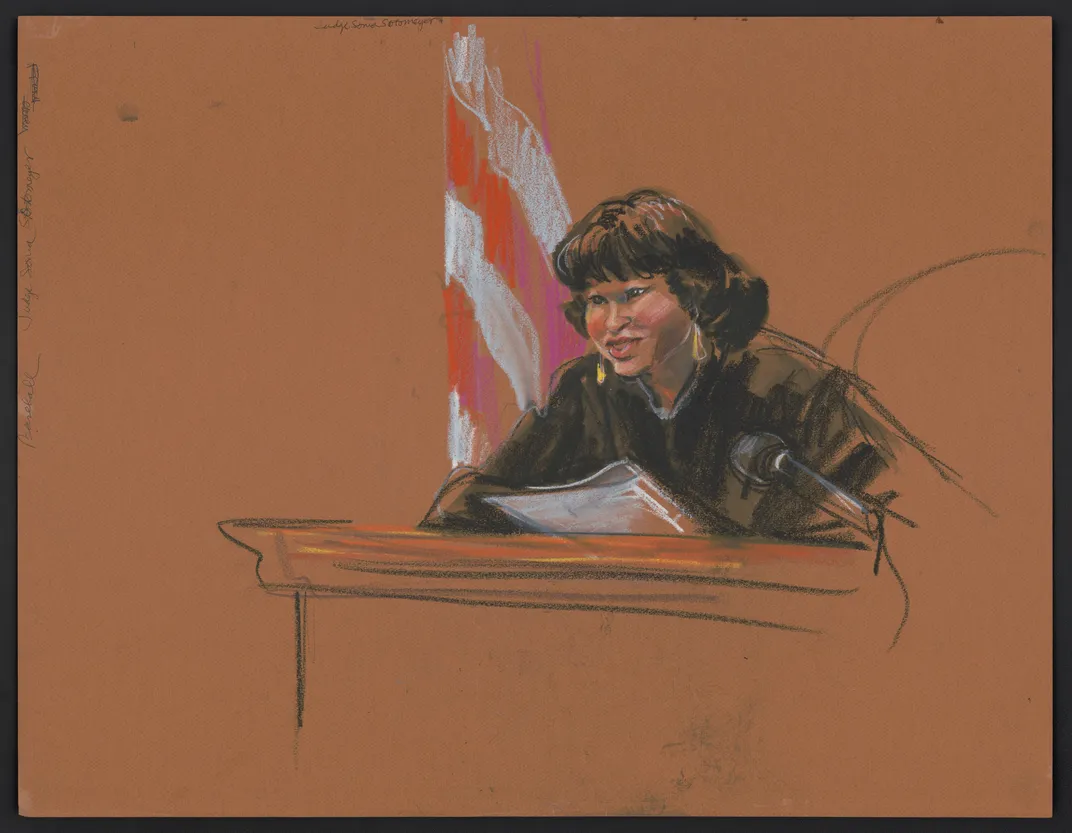

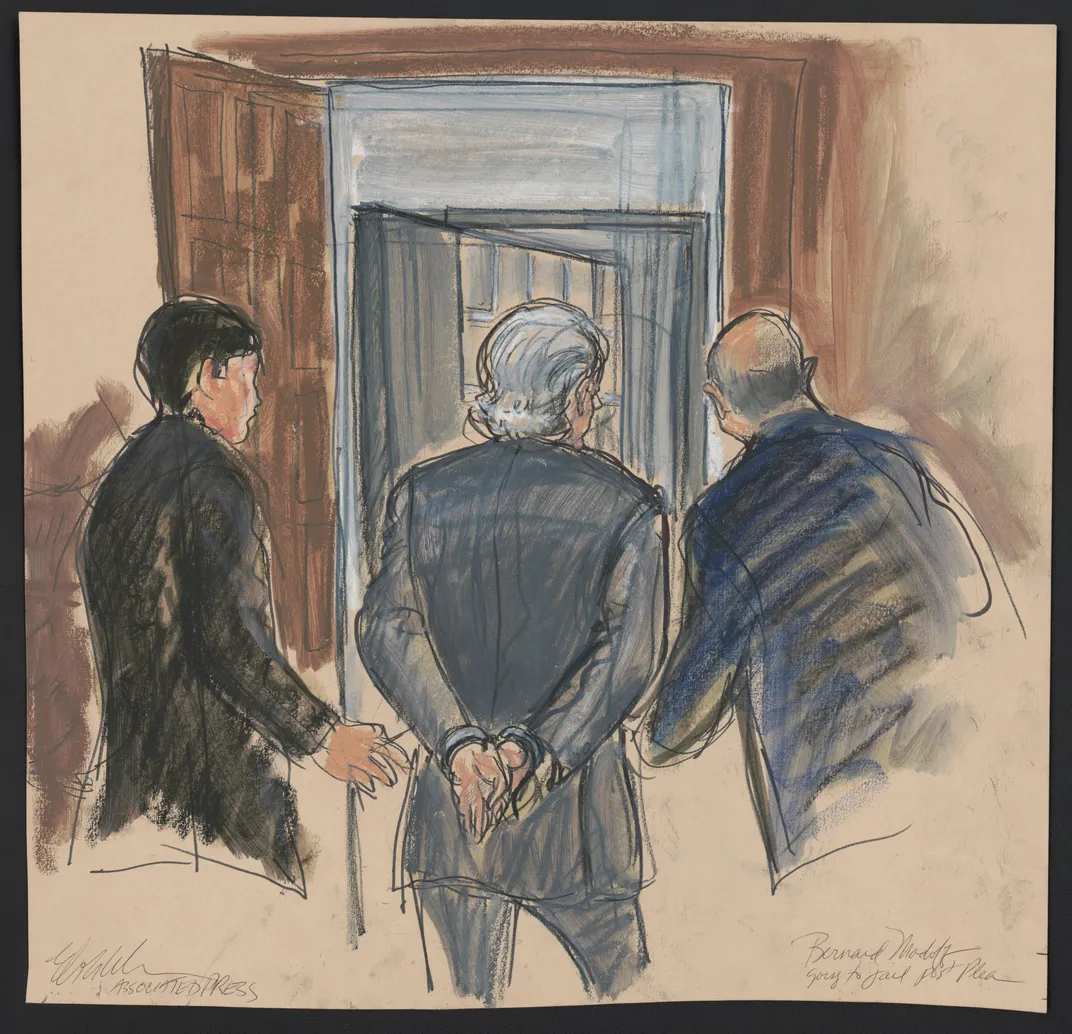

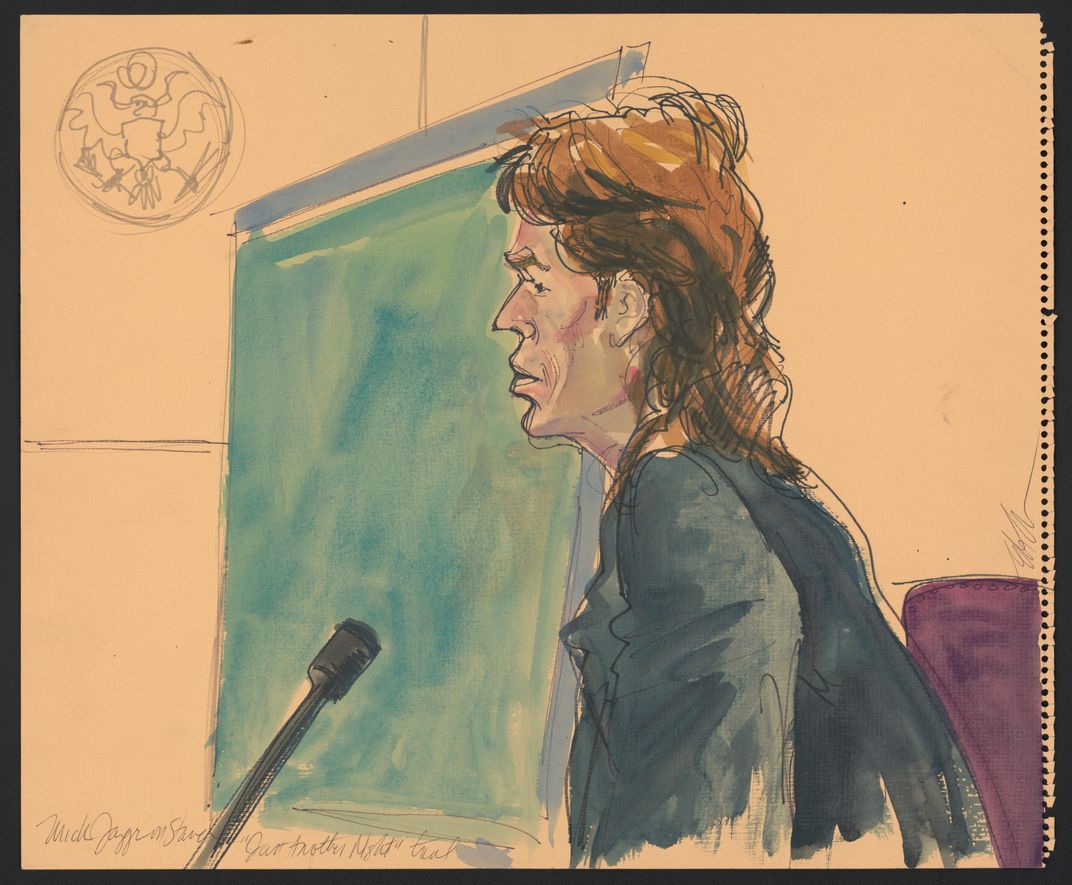

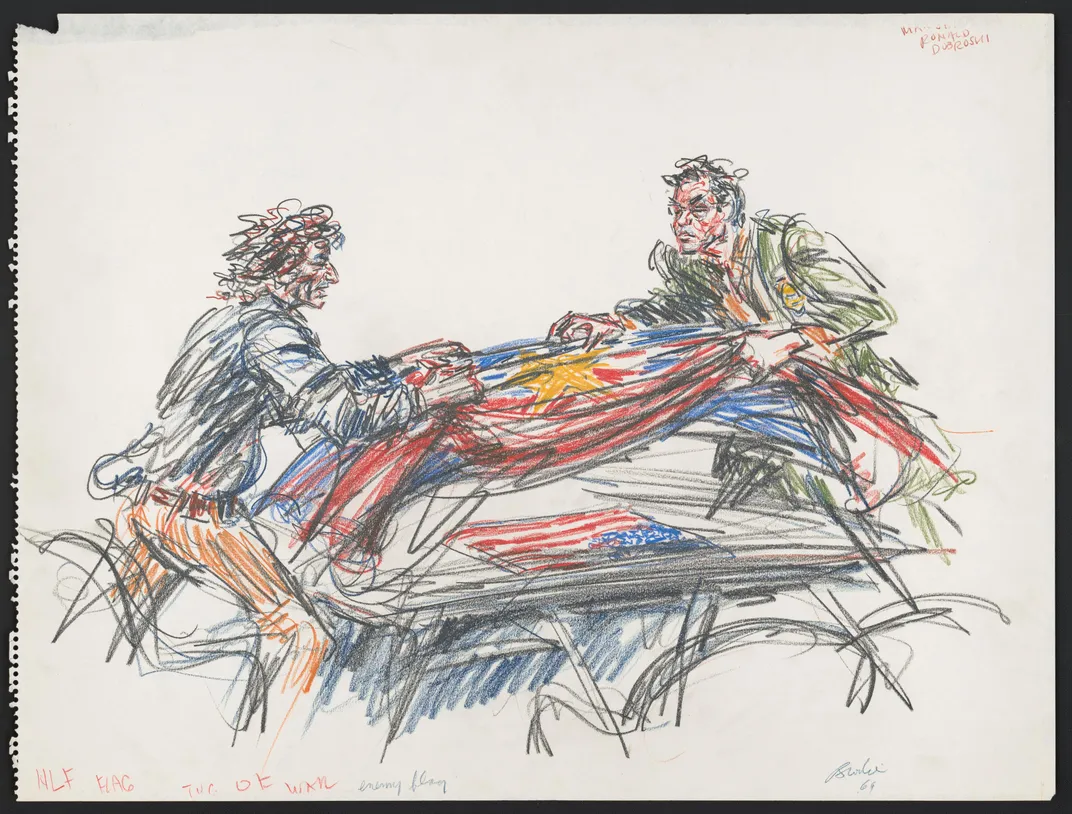

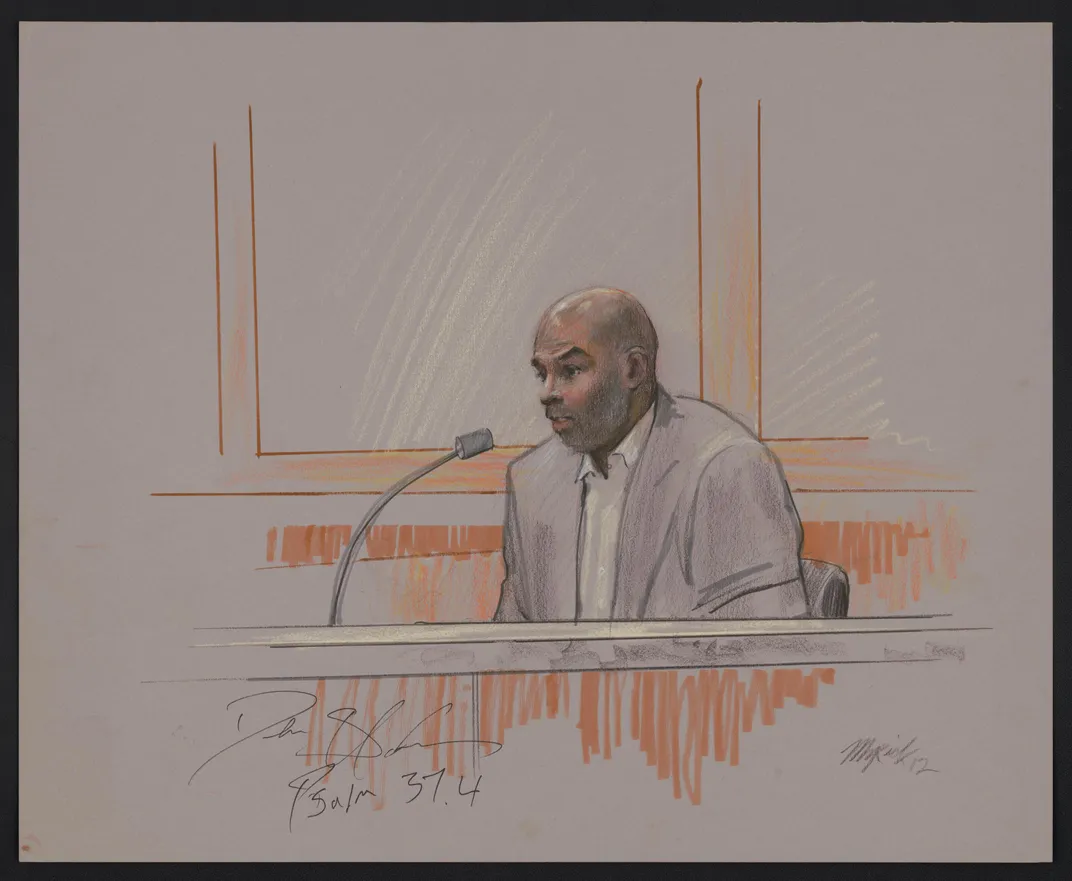

Robes’ drawing of the Manson trial, along with nearly 100 works by other courtroom artists, are now on display at the Library of Congress, Michael Cavna reports for the Washington Post. The exhibit, titled Drawing Justice, takes visitors through more than five decades of courtroom sketches, highlighting a range of different styles and approaches. The men and women who drew these sketches were tasked with capturing the essence of murderers and mobsters, terrorists and thieves, drug peddlers and dissidents.

“[A]rtists don’t act merely as recorders of a moment,” Sara Duke, curator of Drawing Justice, says in an interview with the Post. “They distill for us how people gesture, their relationships to other people in the room and moments of action in the court that define the trial.”

Drawing Justice begins with a 1964 work by Howard Brodie, who covered the trial of Jack Ruby, the Library of Congress press release details. Ruby shot and killed Lee Harvey Oswald, who days earlier had allegedly assassinated JFK. Cameras were banned from the courtroom, so Brodie, a newspaper illustrator, asked a friend at CBS if he could cover the trial. Brodie “became one of the first courtroom illustrators to work for television,” the release explains. One of his sketches, featured in Drawing Justice, shows Ruby gulping nervously as his verdict is read.

The exhibit is rife with drawings of high-profile plaintiffs, including O.J. Simpson and Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers. Also on display are sketches of senate confirmation hearings and depictions of federal and special court cases.

According to the Library of Congress, the modern field of courtroom drawing dates back to the 1930s, specifically to the “Lindbergh baby” trial—and all the hysteria surrounding it. The New Jersey courtroom that hosted the trial of a carpenter named Bruno Richard Hauptmann charged with kidnapping and murdering the infant son of famous aviator Charles Lindbergh was stuffed to the brim with reporters, photographers, and videographers. Flashing cameras and whirring newsreels added to the chaos of the "trial of the century," prompting the American Bar to ban all cameras from future court cases, West’s Encyclopedia of American Law explains. In order to continue their coverage of dramatic courtroom proceedings, news stations “relied on artists' depictions to give viewers a visual sense of the proceedings,” the Library of Congress writes.

Since the 1970s, many states have relaxed restrictions on camera use during trials, which in turn has lessened the demand for courtroom artists. But when cameras are barred from legal proceedings, talented illustrators continue to sketch—giving the public its only glimpse into the thorny, turbulent trials.